Devotion and Decadence

The Berthouville Treasure and Roman Luxury

Institute for the Study of the Ancient World, New York City

October 17, 2018 - January 6, 2019

Reviewed by Ed Voves Original photos by Anne Lloyd

"All roads lead to Rome" was a proverb based on the extensive communication network which bound the provinces of Europe, North Africa and the Middle East to the capital city of the Caesars. At the very heart of this infrastructure, the veins and arteries of the Roman Empire, was a milestone to mark the central spot, a marble column covered in gilded bronze called the Milliarium Aureum.

Nine hundred miles from this fabled marker was a crossroads in the region of France we call Normandy. In Roman times, the place was called Canetonum and was the site of a temple to the god Mercury. Today, the village of Berthouville marks the spot. Then and now, the location was not of strategic importance. But what was under the soil was a different matter.

For nearly fifteen hundred years, a fabulous treasure lay buried, a hoard of silver statuettes, ceremonial cups, vases, utensils and plate. The greatest trove of silver art objects to survive from ancient times, these artifacts date to the height of Rome's grandeur. Now, for a limited time, the Berthouville Treasure is on view at the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World (ISAW) in New York City.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2018)

Gallery view of the Berthouville Treasure exhibition at the ISAW

The ISAW is located two blocks from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 15 E 84th St. ISAW is a graduate school of New York University. It does not have an art collection of its own, but mounts outstanding exhibitions of works from other museums. You won't have to search your pockets for a spare sesterce or drachma to pay the admission price of ISAW. The exhibitions there are free of charge.

The Berthouville Treasure normally resides in the Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF), in Paris. When the BnF closed its galleries for renovation in 2010, the Getty Museum in Los Angeles undertook a massive conservation effort of these ancient art works. After four years of careful study and treatment, the restored Berthouville artifacts went on display at the Getty and several other U.S. museums. The ISAW exhibition is the final display of these treasures before they return to France.

The wonder of the Berthouville Treasure is that it survived all. There were many dangers to this array of precious objects from the Temple of Mercury Canetonensis. But the most perilous moment came with its rediscovery in March 1830. A French farmer, Prosper Taurin, was plowing his field when he unearthed a Roman-era tile. Beneath were ninety-odd silver objects.

Bowl with a Medallion Depicting Omphale, 1–100 CE

Taurin, like most French peasants was not flush with cash. After digging-up the treasures (with his pick-ax!), Taurin decided to travel to a nearby town which had a goldsmith. He planned to employ the goldsmith to melt the artifacts down for the weight value of the silver. Fortunately, Taurin stopped to show his discovery to his cousin. At his cousin's urging, Taurin took the treasures to the local antiquarian society instead of the goldsmith. These worthies convinced Taurin to sell the wondrous silver objects to a museum, thus preserving them for posterity.

The authorities at the Louvre and the Bibliothèque nationale de France took note. When the Berthouville Treasure was placed on auction, a bidding war ensued. The BnF won. Taurin walked away from the sale, a much wealthier man than had he ignored his cousin's advice.

Following their lucky escape, the Berthouville Treasures were studied by French scholars. The most intriguing question concerned the prominence given to the god Mercury. Two statuettes, four phialae or libation bowls and a ladle all bear Mercury's image. Clearly, Mercury was an important deity to the Celtic peoples who inhabited the area around Berthouville in ancient times.

We know a great deal about the Celts of what is today France - but through the testimony of their Roman conqueror, Julius Caesar.

Statuette of Mercury from the Berthouville Treasure , 175–225 CE

Of the Celts, Caesar wrote in The Gallic War, "The god they reverence most is Mercury. They have very many images of him."

Mercury, the messenger god, was the divinity who protected merchants and traders and helped them gain financial success. There was a similar god in the Celtic pantheon, Lugus, whom the Romans equated with Mercury. So there was indeed some justification for Caesar's claim.

To the Celts, however, Mercury had a much more important role. He acted as guide for the souls of newly deceased humans on their journey to the afterlife.

The Celts had a highly developed belief in the immortality of soul and body. This conception of the "hereafter" animated their prowess as warriors and extreme individualists. The amazing - and formidable - Celtic race lacked a written language but had a complex and sophisticated culture which Caesar's conquest, 58-51 BC, and the later Roman invasion of Celtic Britain did not destroy.

During the years following Prosper Taurin's discovery, archaeological surveys revealed the existence of of a temple complex close to where the Berthouville Treasure had been unearthed. Given the numerous examples of Mercury-inspired art works in Taurin's haul and the role of Mercury as guardian of souls, it is surely correct to identify the temple at Canetonum/Berthouville as a shrine to Mercury.

Nine of the silver objects were donated to the Temple of Mercury Canetonensis by an individual named Quintus Domitius Tutus. His identity has not been established, so we do not know if he was a Roman living in Gaul or a Romanized-Celt.

Nor are we sure of when Tutus lived. I suspect that he lived during the mid-second century, the era of the "Good Emperors" when a Roman citizen's words and deeds still retained their value.

Of this rare moment, Edward Gibbon declared, "If a man were called to fix the period in the history of the world, during which the condition of the human race was most happy and prosperous, he would, without hesitation, name that which elapsed from the death of Domitian to the accession of Commodus."

If Quintus Domitius Tutus lived during this period, then he did indeed have something to thank the gods for.

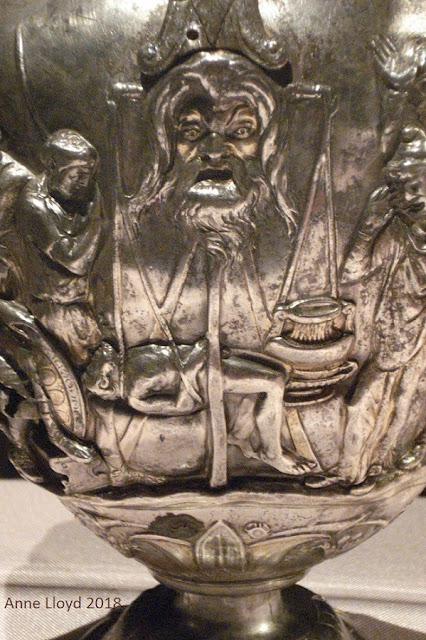

The introductory image for this review, Cup with Centaurs and Cupids, is one of his donations. It is a superbly crafted work, made during the first century after Christ. This and the other pieces donated by Tutus were "high-end" works of art, either extremely valuable personal possessions or purchased specifically to be given to the Temple of Mercury.

Cup with Centaurs and Cupids seems excessively ornate and hedonistic to be a presentation object to a temple, even by Roman standards. Yet, on the bottom is inscribed: MERCVRIO AVGVSTO Q DOMITIVS TVTVS EX VOTO ” (To Augustan Mercury, Quintus Domitius Tutus in fulfillment of a vow).

Pitcher with Scenes from the Trojan War of Achilles and Eight Greek Warriors Weeping over the Body of Patroclus, 1–100 CE

I thought the same about the pair of pitchers decorated with gruesome scenes from the Trojan War. Of course, it is a huge error to read contemporary standards of belief into the art and culture of the past. Yet, Quintus Domitius Tutus, whether he was a citizen of the second century or later, lived in an era when people were searching for a deeper spirituality. Why would he donate these objects, reeking of war and slaughter, to the Temple of Mercury?

Anne Lloyd , Photo (2018)

Silver Pitcher from Berthouville with Scenes from the Trojan War,

showing Priam’s Embassy to Ransom Hector’s Body

When I focused on the back of one of the pitchers, my opinion swiftly changed. I was deeply moved by the scene of the body of the slain Trojan hero, Hector, being weighed in order to fix the amount of ransom so that it could be properly buried. Here was the price of human cruelty memorably depicted!

Anne Lloyd , Photo (2018)

Detail of Scenes from the Trojan War,

showing Priam’s Embassy to Ransom Hector’s Body

Given the deep-seated Celtic belief in the immortality of the soul, I think it likely that Quintus Domitius Tutus chose art works of great spiritual value to donate to the Temple of Mercury. The sensitive depiction of the corpse of the heroic Hector establishes this silver pitcher as a remarkable visualization of human fate. It certainly would have affected a Celt or Romanized-Celt during the later Roman Empire far differently than a Greek or Roman of earlier centuries.

The works of art donated by Tutus were not destined to be on view for long. The third century A.D. was marked by a calamitous downturn in Rome's fortunes from the time of the "Good Emperors." Endless civil wars sapped the strength of the Roman legions and in the year 276 a huge incursion of Germanic barbarians broke through the defenses along the Rhine River. Ironically, the tribe of Franks, who ultimately gave their name to France, were in the vanguard of the assault.

The Temple of Mercury Canetonensis was burned at some point during the third century, though whether it was a casualty of Roman civil war or barbarian invasion is unresolved. The Berthouville Treasure was buried in order to save it from being carried off as spoils of war.

It is no mystery why the Berthouville Treasure remained below ground until the plowshare of Prosper Taurin broke through the sleep of centuries. The Roman Empire nearly collapsed around the time of the destruction of the Temple of Mercury Canetonensis. Rome's control of what is now northern France and the Rhineland in Germany remained tenuous until the Western Roman Empire finally expired in 476.

This was the age of "hoards," stashes of precious objects or gold and silver coins, hurriedly buried as barbarians or mutinous legions rampaged across the landscape. Many of the owners did not live to reclaim their buried treasures

The ISAW includes a number of surviving artifacts which have come to light over the years, along with the Berthouville Treasure. These include the "Patera of Rennes," a spectacular golden plate decorated with mythological characters and coins of Roman emperors. This was found in Brittany where many British Celts fled to escape the invading Saxons during the fifth and sixth centuries.

Offering Bowl with Bacchus, Hercules, and Coins, "Patera of Rennes." ca. 210 CE

Fished from the Rhone River, a similar plate, made of silver, shows a scene from the Iliad much like the ones on the silver pitchers dedicated by Quintus Domitius Tutus

.

Plate with the Embassy to Achilles (The Shield of Scipio), 375–400 CE

Amazingly, this impressive silver plate dates to the years 375–400. This was almost four centuries after the works bequeathed by Tutus were created. Even as vast geopolitical forces reshaped their world, the people of the Roman Empire clung to the old "favorites," motifs from the classical past, when commissioning new works of art.

This Plate with the Embassy to Achilles and the treasures from Berthouville would seem to confirm the French saying that "the more things change, the more they stay the same."

Actually, the true significance of the Berthouville Treasure is the very opposite of this oft-quoted remark. The Berthouville Treasure points to monumental change. These precious objects testify to the fusing together of Celtic culture with the Classical civilization of the Mediterranean world to form the foundation of a new, dynamic political state.

If all the roads of Imperial Rome terminated at the Milliarium Aureum, the Berthouville Treasure marks the spot where the nation of France began.

***

Text: Copyright of Ed Voves, all rights reserved

Images courtesy of the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World, New York University and Anne Lloyd.

Introductory image: Cup with Centaurs and Cupids. Roman, 1–100 CE. Findspot: Berthouville, France. Silver and gold: H. 11.7 cm; W. 26.8 cm; D. 17.4 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris: Inv. 56.7. Photo: Tahnee Cracchiola © Getty-BnF. Inscribed: “MERCVRIO AVGVSTO Q DOMITIVS TVTVS EX VOTO ” (To Augustan Mercury, Quintus Domitius Tutus in fulfillment of a vow)

Anne Lloyd , Photo (2018) Gallery view of the exhibition at the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World, NYC, showing the Statuette of Mercury from the Berthouville Treasure. Photo taken with the special permission of the ISAW.

Bowl with a Medallion Depicting Omphale. Roman, 1–100 CE. Findspot: Berthouville, France. Silver and gold: H. 8.2 cm; Diam. 28.9 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris: Inv. 56.11. Photo: Tahnee Cracchiola © Getty-BnF. Inscribed: “MERCVRIO AVGVSTO Q DOMITIVS TVTVS EX VOTO ” (To Augustan Mercury, Quintus Domitius Tutus in fulfillment of a vow)

Statuette of Mercury. Roman, 175–225 CE.Findspot: Berthouville, France. Silver and gold: H. 56.3 cm; Diam. 16 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris: Inv. 56.1. Photo: Tahnee Cracchiola © Getty-BnF.

Pitcher with Scenes from the Trojan War of Achilles and Eight Greek Warriors Weeping over the Body of Patroclus, Priam’s Embassy to Ransom Hector’s Body, and Episodes from the Life of Achilles. Roman, 1–100 CE. Findspot: Berthouville, France. Silver and gold: H. 29.9 cm; W. 14.5; Circumference. 42 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris: Inv. 56.4. Photo: Tahnee Cracchiola © Getty-BnF. Inscribed: “MERCVRIO AVGVSTO Q DOMITIVS TVTVS EX VOTO”. (To Augustan Mercury, Quintus Domitius Tutus in fulfillment of a vow)

Anne Lloyd , Photo (2018) Pitcher with Scenes from the Trojan War with Achilles and Eight Greek Warriors Weeping over the Body of Patroclus, Priam’s Embassy to Ransom Hector’s Body, and Episodes from the Life of Achilles. Photo taken with the special persmission of the ISAW.

Anne Lloyd , Photo (2018) Pitcher with Scenes from the Trojan War, showing Priam’s Embassy to Ransom Hector’s Body (Detail). Photo taken with the special permission of the ISAW.

Offering Bowl with Bacchus, Hercules, and Coins, "Patera of Rennes." Roman, ca. 210 CE. Findspot: Rennes-le-Château, France. Gold: H. 4 cm; Diam. 25 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Département des Monnaies, médailles et antiques, Paris: Inv. 56.94.

Plate with the Embassy to Achilles (The Shield of Scipio). Roman, 375–400 CE. Findspot: In the Rhône, near Avignon, France. Silver and gold: Diameter. 71 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris: Inv. 56.344. Photo: © BnF

No comments:

Post a Comment