Sculpture in the Age of Donatello:

Renaissance Masterpieces from Florence Cathedral

February 20, 2015 to June 14, 2015

Reviewed by Ed Voves

There is always a touch of wistfulness lurking in my emotions when I leave an art exhibition. Outstanding works of art, many of which have not been displayed together in centuries, are joined in unforgettable configurations of genius. After a few months, the exhibit closes. The masterworks are packed in crates and sent back to the museums and collections from which they came.

The magic moment is over.

In the case of Sculpture in the Age of Donatello at the Museum of Biblical Art in New York City, actual sorrow mixed with my feelings of awe at seeing these wonders of Renaissance art. Not only the exhibition, but the museum itself was scheduled to close in a few days. The iron grip of financial "reality" was about to claim another venue of artistic expression.

The Museum of Biblical Art in New York City (MOBIA) opened in 1997, under the direction of the American Bible Society. In 2005, MOBIA became an independent museum, albeit one without a permanent collection of its own. MOBIA paid the American Bible Society $1 per year to rent the second floor of its Columbus Circle area headquarters. It was a beautiful arrangement, allowing MOBIA to mount high caliber exhibitions of religious art.

Gallery view of the Museum of Biblical Art during the Sculpture in the Age of Donatello exhibit

Organizing Sculpture in the Age of Donatello: Renaissance Masterpieces from Florence Cathedral was MOBIA's most brilliant success. But in 2014, the American Bible Society decided to move to Philadelphia and sold its building. As record numbers of patrons visited Sculpture in the Age of Donatello, MOBIA scrambled to raise the funding to rent a new site. With only a few months to do so, MOBIA faced an impossible task.

This depressing scenario is also rich in irony. The final exhibit at MOBIA brought treasures from the Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore, the museum attached to the cathedral of Florence. Santa Maria del Fiore is better known as the Duomo or House of God. The Duomo, as is well-known, was the creative - and spiritual - heart of Florence during the Renaissance.

The works of art in the MOBIA exhibit virtually define Western conceptions of religious faith and devotion. Sculptures by Donatello (1386-1466) and by his colleague and rival, Nanni di Banco (c. 1384 – 1421) were the centerpieces of the show.

Luca della Robbia & Antonio di Salvi Salvucci, Processional Cross, 15th century

An exquisite processional cross created by Luca della Robbia (1400-1482) was another highlight, along with a series of series of hexagonal panels celebrating the intellectual pursuits of Florence. One of these showed a grammar teacher instructing his students, a perfect illustration of Renaissance learning in action.

Luca della Robbia, The Art of Grammar, 1437-39

How could MOBIA go from organizing and mounting such an impressive exhibition to closing its doors forever? A comparison of Florence's S. Maria del Fiore Cathedral with MOBIA provides telling insight into the comparative expressions of religion and culture in Renaissance Italy and modern-day America.

Construction of the Duomo took place over 165 years. The keystone of S. Maria del Fiore was laid on September 8, 1296. The cathedral's stunning dome, designed by Filippo Brunelleschi in 1418 and completed in 1436, was represented in the MOBIA exhibit by the actual working model of this astonishing edifice. The crowning touch, the Lantern of the Cupola, was set high atop the dome, in 1461.

Filippo Brunelleschi, Model for the Dome of Santa Maria del Fiore, ca. 1420–52

Taking American history as a comparison, these 165 years match the long course of American democracy, from 1776 to the U.S. entry into the Second World War in 1941. That is a long time to build a church. The Duomo, however, is not just any church. The Florentines knew that and the sculptures from S. Maria del Fiore that MOBIA displayed proved that they knew it.

Two statues were given pride of place, side-by-side in the MOBIA exhibit, St. Luke the Evangelist and St. John the Evangelist. These impressive works of art asserted the piety and self-confidence of Florence during the 1400’s in a way that is almost impossible to conceive today. Renaissance Florence managed to combine mercantile skill, political pragmatism and fidelity to the Christian faith with cultural awareness of Greek and Roman antiquity. These traits are well-attested to in the marble men of God sculpted to adorn the Duomo.

Nanni di Banco, St. Luke the Evangelist, 1408–13

St. Luke the Evangelist, sculpted by Nanni di Banco around 1408–13, embodies the intellectual mindset known as Humanism. This innovation of the Renaissance made the role of individual scholars, rather than scholastic theory, the keystone of intellectual inquiry. The keen-eyed Apostle Luke appraises passers-by and the world at large from his niche on the wall of the Duomo.

Nanni di Banco's St. Luke resembles the Roman emperor Hadrian, an indication of the zeal of Renaissance humanists for studying the surviving art works of antiquity. By contrast, Donatello's St. John the Evangelist played an important role in how the image of God came to be presented in Western art.

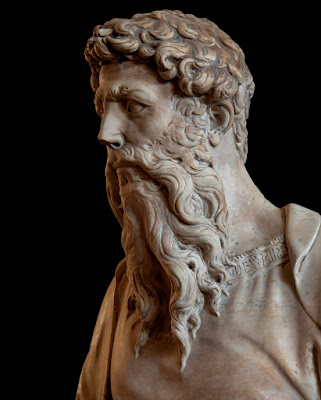

Donatello, St. John the Evangelist, 1408–15

During the Middle Ages, God the Father was almost never depicted, save as a disembodied arm sending the Holy Spirit winging down to earth. In a daring stroke, Lorenzo Ghiberti showed the torso, head and outstretched arms of God the Father in the Annunciation panel of his North Doors for the Florence Baptistery, created between 1403-24. God's face, however, is largely obscured.

When Ghiberti created his second set of doors for the Baptistery, the famed "Doors of Paradise," God was shown as a long-bearded sage not unlike Michelangelo's Supreme Being on the Sistine Chapel Ceiling. More to the point, Ghiberti's God the Father looked like Donatello's St. John, completed a few years earlier in 1415.

Did Donatello influence Ghiberti or was it the other way around? Donatello assisted Ghiberti with the North Door panels during the early years of the project, before he started sculpting St. John in 1408. Donatello was almost certainly influenced by Ghiberti's depiction of the long-bearded Abraham poised to sacrifice Isaac in the competition piece that enabled him to best his rival Brunelleschi to gain the commission for the Baptistery doors.

The answer to this question lies in the creative rivalries and relationships in the small, brilliant circle of the Florentine art world during the early 1400's. Donatello, Ghiberti, Brunelleschi and the rest mutually influenced the techniques and achievements of each other - and succeeding generations of artists. When we look at the powerful, visionary countenance of Donatello's St. John the Evangelist we are looking at the face of Western art from the Renaissance onward to Rodin in the nineteenth century.

Donatello, St. John the Evangelist (Detail), 1408–15

The great artistic drama in Florence during the 1400's centered on the sculptural decoration of the Duomo and other places of worship like the Church of Santa Croce. It was a wise decision by the curators of the MOBIA exhibit to extend the range of artists to include ones of lesser talent than Donatello because virtually every Florentine artist of note was involved in the sustained programs of ecclesiastical art.

Attributed to Giovanni d’Ambrogio, Archangel Gabriel and the Virgin Mary

The two-figure ensemble of the Archangel Gabriel of the Annunciation and the Virgin Mary of the Annunciation, attributed to Giovanni d'Ambrogio during the late 1300's, is a case in point. Etched into the faces of Gabriel and Mary are intense emotions which in turn reveal the deep psychological roots of the Renaissance in Italy. This great artistic revolution was not the product of two or three isolated "genius" figures. The spirit of that remarkable age encompassed the many not the few.

Donatello - Donato di Niccolò di Betto Bardi - was a genius and a long-lived one at that. By the time he died in 1466, aged 80, his vast, innovative and varied body of work encompassed the entire epoch of the early Renaissance. Several of the disturbing works of his later career, such as the Penitent Magdalene, which he carved in wood around 1455, pointed to the political and religious discord that marked the later stages of the Renaissance.

Indeed, it is not an exaggeration to see social stress fractures beginning to appear in a relatively early work and one that Donatello was reputed to have spoken to as if it were alive. This statue, created around 1435, is believed to depict the Old Testament prophet, Habakkuk.

Donatello, Prophet (possibly Habbakuk), 1435–36

With a typical Italian blend of affection and irreverence, the statue of Habakkuk has long been called lo Zuccone or "Squash Head." When viewing this mighty work in person, the wittiness of its nickname can become rather annoying. The mind behind the tormented face of Habakkuk has other ideas. Lips parted as if to speak, Habakkuk scores a direct hit on the complacency and self-satisfaction of the viewer - without saying a word.

As the excellent essay in the companion volume to the exhibit notes, the Prophet Habakkuk proclaimed in the Old Testament that "... the just shall live by his faith."

Donatello, Prophet (possibly Habbakuk), (detail), 1435–36

Any society which devotes so many resources, so much talent and zeal to church building as the Florentines did during the 1300's and 1400's is obviously a faith community. But Donatello's Habakkuk is speaking to a primal level of religious belief for those times when our lives and souls are not protected by the walls of the Duomo. Faith at this level is an act of courage, physical and moral, when menaced by tyranny and death. It is a voice saying yes to God when the rest of the world says no.

Donatello's Habakkuk speaks of values that an institution like MOBIA is best equipped to present. No art museum is - or should be - a surrogate church. MOBIA was designed to present religious art in a sensitive, non-sectarian manner. By doing so, MOBIA allowed the moral values of the works on view to be evoked without endorsing them. This unique and dearly-needed artistic environment is very rare, apart from the Metropolitan Museum's Cloisters and a few other venues.

When MOBIA closed its doors on June 14, 2015, a major loss to American culture took place. How sad that an American foundation could not have stepped forward to assist MOBIA to find a new home. The guilds of Florence played a direct role in funding the Duomo and the incomparable art created by Donatello and Ghiberti.

MOBIA's closing raises real questions about the values of the present-day. Are we a society that stamps "In God We Trust" on the coin of the realm but fails to support a museum dedicated to the study of the Bible upon which the values of the West are ultimately founded?

MOBIA's closing raises real questions about the values of the present-day. Are we a society that stamps "In God We Trust" on the coin of the realm but fails to support a museum dedicated to the study of the Bible upon which the values of the West are ultimately founded?

The answer to that question may be more important than we realize.

***

Text: Copyright of Ed Voves, all rights reserved

Images courtesy of the Museum of Biblical Art (MOBIA), New York City

Introductory Image:

Installation view of Sculpture in the Age of Donatello: Renaissance Masterpieces from Florence Cathedral at the Museum of Biblical Art, 2015. Photo by Eduard Hueber. The exhibition is organized by Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore, Florence, and the Museum of Biblical Art, New York

Installation view (Interior) of Sculpture in the Age of Donatello: Renaissance Masterpieces from Florence Cathedral at the Museum of Biblical Art, 2015. Photo by Eduard Hueber. The exhibition is organized by Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore, Florence, and the Museum of Biblical Art, New York

Installation view (Interior) of Sculpture in the Age of Donatello: Renaissance Masterpieces from Florence Cathedral at the Museum of Biblical Art, 2015. Photo by Eduard Hueber. The exhibition is organized by Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore, Florence, and the Museum of Biblical Art, New York

Luca della Robbia and Antonio di Salvi Salvucci, Processional Cross: Christ Crucified, the Evangelists, Allegory of the Sun, 15th century (after 1460, before 1475), Gilded copper (repoussé and chased), gilded bronze, and enamel, 76 × 57 cm (total height with staff: 160 cm) (30 × 22½ in.) (total height with staff: 63 in.) Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore, inv. no. 2005/347 © Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore / Antonio Quattrone

Luca della Robbia, The Art of Grammar (Aelius Donatus or Priscian instructing students?), 1437-39, Marble, 81.5 × 68.5 × 13 cm (32 × 27 × 5 in.) Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore, inv. no. 2005/436 © Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore / Antonio Quattrone

Attributed to Filippo Brunelleschi, Model for the Dome of Santa Maria del Fiore, ca. 1420–52, Wood, dome: 100 × 70 cm (393⁄8 × 27½ in.); apses: 55 × 63 × 35 cm each (215⁄8 × 24¾ × 13¾ in. each) Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore, inv. no. 2005/493 © Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore / Antonio Quattrone

Nanni di Banco, St. Luke the Evangelist, 1408–13, Marble, 207 × 91 × 63 cm (81½ × 357⁄8 × 247⁄8 in.) Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore, inv. no 2005/112 © Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore / Antonio Quattrone

Donatello, St. John the Evangelist, 1408–15, Marble, 212 × 91 × 62 cm (83½ × 35¾ × 24½ in.) Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore, inv. no 2005/113 © Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore / Antonio Quattrone

Attributed to Giovanni d’Ambrogio, Archangel Gabriel of the Annunciation, late 14th century, Marble, 144 × 44 × 30 cm (56¾ × 17¼ × 117⁄8 in.) Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore, inv. no. 2005/276 © Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore / Antonio Quattrone

Attributed to Giovanni d’Ambrogio, Virgin Mary of the Annunciation, late 14th century, Marble, 144 × 44 × 30 cm (56¾ × 17¼ × 117⁄8 in.) Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore, inv. No 2005/277 © Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore / Antonio Quattrone

Donatello, Prophet (possibly Habbakuk), known as the Zuccone, 1435–36, Marble, 195 × 54 × 38 cm (763⁄4 × 211⁄4 × 15 in.) Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore, inv. no. 2005/374 © Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore / Antonio Quattrone

Marvelous article, thank you for posting. Whether by looting such as in Baghdad or financial collapse, it's not a good sign for a society generally when museums close. And how ironical that even one devoted to Biblical themes cannot keep its doors open.

ReplyDeleteTerrific article. Art has been divorced from religion in the west, I think to the detriment of both. Art for the church at least has a democratic element; anyone in Florence could enjoy these beautiful works, in contrast to the very small number of people who have access to the high-priced contemporary art being traded today.

ReplyDelete