David Hockney: Drawing from Life

The Morgan Library and Museum October 2, 2020 through May 30, 2021

Reviewed by Ed Voves

On October 22, 2020, Christies's auctioned a realist-style portrait painted in 1970. The subject of the work was Sir David Webster, the chief executive of the Royal Opera, who was about to retire. Webster had played a huge role in the post-World War II rise of the Royal Opera and the Royal Ballet to world-class status. The selling price of the painting, however, was not predicated on Webster's considerable achievements. Instead, it was the identity of the painter which determined its cost.

The price tag of Sir David Webster was £12.8 million, the equivalent of $17 million. It was painted by David Hockney.

Sir David Webster is a masterful work, leaving us to ponder an important question. The pros and cons of the selling price are not the issue. Why did Hockney not devote himself to portrait painting as his primary form of visual expression?

For those fortunate to be able to make the journey to see the current exhibition at the Morgan Library and Museum in New York City, David Hockney: Drawing from Life, that question will be even more perplexing.

With over 100 works of art on view at the Morgan, the exhibit ranges from Hockney's student self-portraits to iPhone and iPad portraits of recent years. Whatever the artistic medium or stage of his career, David Hockney is one of the great contemporary masters of the human likeness.

As the title of the Morgan exhibition affirms, this is a drawing show. Hockney was trained in the classical regimen of instruction, founded on draughtsmanship. Approximately 100 drawings, in all media, are displayed.

Most of the the drawings are finished works of art, but some of the most amazing are preparatory studies.

Hockney's sketch for the joint portrait of his parents recalls Las Meninas by Velazquez but does not seem the least bit affected or derivative. Hockney's mirrored visage, in the very center of the sketch, emphasizes the centrality of his life in the lives of his parents and theirs in his.

Another salient point in the Morgan exhibit is Hockney's embrace of innovative ways and new technology to create images. However, whether using the Rapidigraph technical pen early in his career or the iPad today, Hockney created works of enduring value. The tools or technique Hockney uses are always the means, never an end in itself, of art.

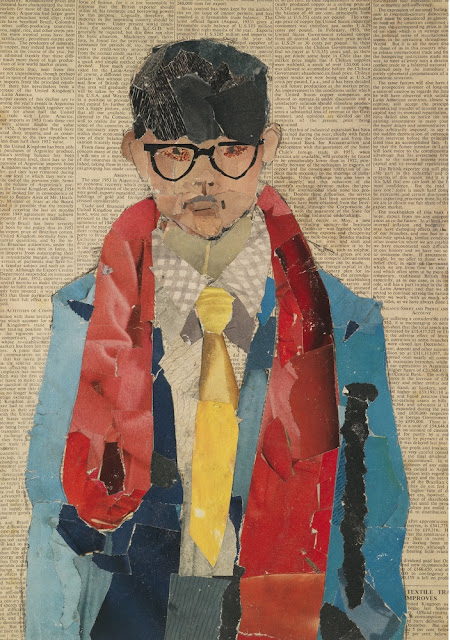

That point is clear from one of the earliest works on view in the Morgan exhibition. Self Portrait, 1954 is a collage on newsprint, made when Hockney was just seventeen. It was created by cutting-up glossy magazine pictures and using the "bits" to piece together an impressionistic image of himself.

In one sense, the young Hockney was experimenting with collage, as Picasso and Braque had done during the early days of Cubism. But more importantly, Hockney was exploring a way to reveal himself, the real David Hockney, to those closest to him.

"What an artist is trying to do for people is bring them closer to something, because of course art is about sharing," Hockney has said, in a much quoted remark. "You wouldn't be an artist unless you wanted to share an experience, a thought."

With portraiture, Hockney aims to share his experiences, his thoughts and most of all, his feelings, with people he knows and loves. It is significant that Hockney, a brilliant student and commentator on art history, prefers the portraits of van Gogh to those of John Singer Sargent,the greatest professional portrait painter of the late 1800's. Like van Gogh, Hockney creates portraits of a very select, very intimate, group of family, friends and confidantes.

The Morgan exhibition focuses on five people who figure prominently in Hockney 's portrait oeuvre: his mother, Laura Hockney, Celia Birtwell, Gregory Evans, Maurice Payne - and himself.

The Morgan exhibition begins with a digital display highlighting Hockney's series of iPad self-portraits, executed in 2012. These reference another of his artistic heroes, Rembrandt. Hockney captures an almost disorienting range of moods, expressions and states-of-mind

Viewed individually, the individual iPad "selfies" cannot match the level of draughtmanship which Hockney achieved with traditional techniques in other works, such as 1998 etching of master/printer and friend, Maurice Payne. Yet, this new medium,when used in serial form, has enabled Hockney to explore the human face and the psychological complexity behind it with revelatory effect.

David Hockney, No. 1201, iPad Drawing, 2012

Before discussing Hockney's relationships with his mother and friends, the influence of a sixth person in his intimate group needs to be noticed: Pablo Picasso.

In 1960, while studying at the Royal College of Art, Hockney visited a major Picasso retrospective and was profoundly affected. For a number of years following the 1960 exhibition, Hockney was much influenced by Picasso's mastery of line.

In 1973, the year of Picasso's death, Hockney paid homage to the Spanish master with an etching which also strikes an irreverent note. It was just the kind of subversive touch which Picasso himself often demonstrated. However much he revered Picasso, Hockney served notice that he would follow Picasso's example, but never walk in his footsteps.

Like Picasso, Hockney has embraced the whole world of art and experience, exploring a style or technique when it suited his purpose or interest. We can see this approach in three very different works dealing with the same person, Hockney's friend - and for some years, his lover, Gregory Evans.

The first is a carefully delineated drawing, using colored pencils to brilliant effect. It is realist art in its classical form, but also much more. Just as Hockney uses the blank, negative space to give a sense of volume to Evan's figure, he manages to convey that part of his friend's inner being which is being held in check. One eye looks directly toward the viewer, the other is fixed on another reality, perhaps an interior realm or somewhere else, off-in-space.

Early in the decade of the 1980's, Hockney experimented with composing collage portraits by means of "joiners." These were photos of slightly similar, but significantly different, views of a face or body. Hockney used Polaroid pictures, joining them to create an image, as can be seen above, a profile of Gregory Evans. The resulting portrait is much more nuanced and intriguing than a single photo could achieve.

“The moment you make a collage of photographs,” Hockney commented, “it becomes something like a drawing.”

Hockney used this composite approach to create a portrait of his mother, My Mother Bolton Abbey, Yorkshire, Nov. 82, which is one of the most moving images in the Morgan exhibition. In a sense, this is a double portrait, as Hockney included the tips of his shoes at the bottom of the image. The shoes could represent himself, his recently-deceased father (who used to visit Bolton Abbey with Hockney's mother) or the viewer who stands before this remarkable work.

Over the decades, Hockney maintained this multi-disciplinary approach in depicting the cherished people in his life. Thus, Hockney's "drawings from life" are also reflections on the aging process and ultimately on mortality.

Hockney charts the passage of time in his depictions of all five protagonists in the Morgan exhibition. In this review, we will look at the way he has portrayed his dear friend of many years, Celia Birtwell.

A native of northern England like Hockney, Celia Birtwell was the "Mrs. Clark" in one of Hockney's most celebrated paintings, Mr. and Mrs Clark and Percy. A talented and stylish fashion designer of the "swinging sixties" London scene, we see her posing in the brilliant 1971 portrait as a woman of two worlds.

Hockney presents Celia Birtwell as a poised, self-assured woman, filling the moment when she posed for the drawing with her presence. This, in turn, carries over to the present moment when we view her. She dominates the meeting of viewer and viewed, reigning over the exchange with a charismatic appeal that the world would later witness in the all-too-short life of Princess Diana.

There is, however, a fey, ethereal quality in Birtwell's green eyes. This might seem contradictory as her eyes are sharply focused on the person standing before her- Hockney in 1971, us now. Yet, in returning her gaze, one gets the unsettling feeling that it is an "otherworldly" Celia Birtwell who posed for Hockney, exuding a spiritual presence more potent than her very real physical charm.

Flash forward from 1971 to 2019 and there once again is Celia Birtwell, posing for her portrait. Birtwell's careworn face, the added pounds on her frame and slumped posture testify that no one, not even David Hockney's muse, can evade the "cost" of living. Yet, once again, we see that her eyes are still alive with the inner radiance that Hockney had depicted almost a half century before.

"We are always the same person inside," Gertrude Stein, declared long ago. For Celia Birtwell, that does indeed appear to be true. Hockney,with an incredible alchemy of skill and insight, has captured the evasive, unquenchable life force which we see in Celia's eyes in both portraits.

How does Hockney, after sixty years, continue to achieve such fantastic results in portraiture, when landscapes, some of monumental size, occupy so much of his time and talent?

Hockney provides the answer in his extended interview with Martin Gayford, A Bigger Message (Thames & Hudson, second edition, 2016). When he looks at people, Hockney takes the time to see them, to really gain their measure. He reaches deep within himself and within them in what can truly be called an "act of seeing."

"Most people don't look at a face too long; they tend to look away," Hockney told Gayford. "But you do it if you are painting a portrait. Rembrandt put more in the face than anyone before of since, because he saw more. That was the eye - and the heart."

***

Text: Copyright of Ed Voves. Original Photos:Ed Voves. All rights reserved

No comments:

Post a Comment