Liberty: Don Troiani's Paintings of the American Revolution

The final days of the American Revolutionary War placed Benjamin Franklin in a very curious state of mind. Franklin, the leader of the American diplomats negotiating the terms of the peace treaty, had every reason to be elated. Victory was in the air. Yet, he was in a melancholy mood, ruminating on the human cost of the conflict.

Writing to fellow scientist, Sir Joseph Banks, in July 1783, Franklin asserted, "There never was a good war or a bad peace."

Reflecting upon the paintings of Revolutionary War battles by contemporary artist, Don Troiani, certainly helps me comprehend Franklin's less-than-exultant remarks. It has been calculated that 24,000 Patriots were killed or died of disease between 1775 to 1783. An equal number of British soldiers and 7,500 Hessian mercenaries paid the price of King George's political folly with their lives. Nobody counted civilian deaths.

Over forty original works of art by Don Troiani bring to life what Thomas Paine memorably called "the times that try men's souls." Complemented by displays of authentic weapons and uniforms, Liberty: Don Troiani's Paintings of the American Revolution is presented by the Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia.

Troiani, who studied at the Pennsylvania Academy of Art, works in the great realist tradition of Thomas Eakins and Winslow Homer. His specialty is military art, especially of the American Revolutionary War. An excellent companion book to the exhibition presents incisive accounts of the battles and events which Troiani depicts in his paintings, along with fascinating details of his artistic technique and experiences in recreating these bygone events.

Although narrative paintings of the kind at which Troiani excels are of vital importance to the study of history, these works rarely receive much attention in the realm of art appreciation. As I hope to show in this review, Troiani's paintings are powerful investigations of human emotions and deserve to be considered as accomplished works of art.

That Troiani's paintings are inspired is evident by the powerful effect these works have on the viewer. This is not an emotional, subjective response on my part, alone, as was confirmed during my visit to the exhibition at the Museum of the American Revolution.

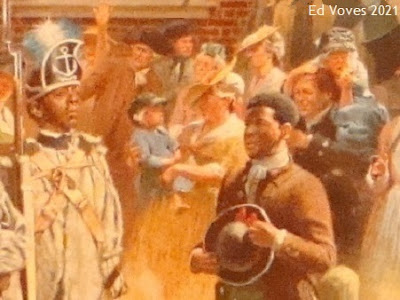

While examining Troiani's art, I had the great honor to speak with Mr. Algernon Ward, who posed in a new painting by Troiani. Entitled As Brave Men as Ever Fought, it records the march of the 1st Rhode island Regiment, a multi-racial unit formed in 1778. Several companies of African-American recruits, including 100 slaves who were emancipated upon joining the unit, participated in military campaigns during the final years of the war, including the decisive battle of Yorktown in 1781.

At the center of the painting, a young African-American, James Forten, watches with pride as the Rhode Island troops march through Philadelphia on their way to Yorktown. Forten was so inspired that he joined the American Navy. He survived the war, including time as a prisoner of war on one of the infamous "hulks", prison ships anchored near New York. Forten went on to become one of the early leaders of the Abolitionist movement of the early 1800's.

Mr. Ward, shown in the detail, above, posed as the Rhode Island soldier nearest to Forten. Ward, a native of Trenton, New Jersey, is active in the "living history" movement. He is a member of the 6th Regiment of the United States Colored Troops, a group which re-enacts the lives of African-American soldiers over the course of U.S. history.

Mr. Ward was visibly moved as he described his experience of modeling as a Rhode Island Regiment soldier for Troiani. Looking at the finished painting makes him feel like he is "floating two feet above ground."

Such moments of inspiration remind us of the great exertions made in the name of liberty. When freedom is at stake, it is not merely a matter of noble words but of blood too - suffering, wounds, death. Troiani's art helps us appreciate Franklin's war-weary reflections. But these vivid, powerful works of art also testify to the self-sacrificing resolve of the 1776 generation.

Spanning the nearly decade-long war, Troiani's American Revolution paintings narrate the course of military campaigns and other important incidents of this pivotal era in history. Stressing absolute accuracy, both in details of uniforms, weapons and battle sites and the grim, often appalling, experience of combat, Troiani has filled a glaring hole in the American historical record.

This gap in American history resulted from the almost complete absence of trained artists on the scene at Lexington and Concord, Princeton, Saratoga and Yorktown. With only a few exceptions, pictures of these historic events, dating to the actual time (or close to it), were not created.

A well-developed system of art education and patronage did not exist in the British colonies prior to 1776 - and for many years after. Yet, lack of trained talent alone does not account for the scarcity of contemporary depictions of the American Revolution. A complicated mix of psychological, political and cultural motives, related to the Age of Reason, drew a curtain over the frequent wars and the very real brutality of the era.

History painting during the eighteenth century generally dealt with the distant past, events from Biblical stories and Greek and Roman times. During the 1700's, only Antoine Watteau, among great artists, created authentic representations of recent warfare. Watteau painted several remarkable scenes of soldier life during the War of the Spanish Succession, 1702-1713.

Right from the first volley of musket fire at Lexington, the American Revolution was different. It was a "people's war" not a dynastic struggle over who would sit on the throne of Spain. It was a conflict where stirring visual depictions of the rebellion against British tyranny might have made a huge impact. Initially, that seemed to be the case.

The first work in the exhibition of Troiani's paintings focuses on the notorious Boston Massacre of 1770. Confronted by a swiftly-escalating riot, a platoon of British infantrymen opened fire on a crowd of brickbat-throwing Bostonians. Paul Revere's crude but effective print of the "massacre" is displayed next to Troiani's more accurate version.

Revere's print helped galvanize the resistance of American Patriots against British rule. However, it was years before another powerful image of the Revolutionary War was created by an American-born artist, one who had fled to England, shortly before the fighting began.

John Singleton Copley's The Death of Major Peirson portrayed a minor incident in the American Revolution after it had become a global war. With most of the British Army fighting in America, French troops tried to seize the English Channel island of Jersey on January 6,1781. Their attempt failed thanks to the heroic defense led by Major Francis Peirson, who was killed early in the fighting.

With Britain clearly losing the war in America, Copley took some of the sting out of the impending defeat with The Death of Major Peirson. He showed valiant Britons fighting to defend their home soil, just as the American Patriots were doing. The Death of Major Peirson was wildly popular when it was displayed in London, without damaging Copley's reputation in America. Even so, Copley never returned to the now independent United States.

The dramatic years between Paul Revere's The Bloody Massacre perpetrated in King Street and The Death of Major Peirson were left an almost blank canvas which various artists later sought to fill. Many of the paintings of the Revolutionary War were only created decades after the event. The results were often simplistic, over-romanticized and in many cases misleading. Not only do Troiani's paintings document events which had earlier been ignored, but he has been setting the record straight for incidents which had been inaccurately represented.

Liberty: Don Troiani's Paintings of the American Revolution makes several important points. Considered according to these insights, the struggle for American independence appears in a more complicated, yet, more inspiring light.

Troiani's paintings show that two "wars" occurred under the overarching title of the Revolutionary War. The first involved set-piece military campaigns, fought according to the conventional tactics of the 18th century. The British usually won these engagements, though at such a cost in blood that "victories" like the Battle of Freeman's Farm led eventually to Patriot triumphs at Saratoga (1777) and Yorktown in 1781.

The second, parallel struggle was an even more terrible conflict. It was marked by raids, ambushes, scorched-earth destruction and cruelty toward prisoners and civilians.This second war was largely an "All American" affair, pitting frontier Patriots vs. Loyalist rangers. It was, in fact, the first American Civil War.

Several of Troiani's paintings on view at the Museum of the American Revolution deal with this brutal "second front." Of these I was particularly impressed, indeed fascinated, by The Oneida at the Battle of Oriskany, August 6, 1777. This bloody, hard-fought struggle in the forests of western New York was notable for the involvement of Native Americans on both sides of the battle line.

One of the most influential factors in the successful establishment of the English-speaking colonies in America was the support of the Six Nations, the Haudenosaunee or Iroquois Confederacy. The help of the Six Nations was especially crucial in winning the French and Indian War, 1755-1763. However, the Revolution broke the unity of this impressive Native American confederation. Most of the member nations, especially the Mohawks, remained allied to the British. However, the Oneida supported the Patriot cause.

During the summer of 1777, pro-British warriors of the Six Nations, along with a small force of British troops and American Loyalists, tried to march across the wilderness of western New York to support the British army under General Burgoyne which was advancing down from Canada. Once the link-up had been achieved, the combined force aimed to cut-off New England from the rest of Patriot-held territory.

The force of British, Loyalists and Native Americans, under Lt. Colonel Barry St. Leger, needed to capture Fort Stanwix (near present-day Rome, N.Y). Before they could do so, a Patriot relief column marched to support the defenders. The resulting battle is powerfully brought to life in one of Troiani's biggest paintings, 50 x 80 inches, which the Oneida Nation commissioned him to paint in 2005.

Troiani's battle scene is a very complex work, especially impressive in the brilliant effects he achieved in depicting dappled sunlight, shrouded by dense clouds of gunpowder smoke. But it is human drama that takes center-stage in this powerful representation of frontier warfare.

Troiani's The Oneida at the Battle of Oriskany is dominated by two, confronting protagonists. On the left is the Oneida warrior, Thawengarakwen, whose name means "He Who Takes Up the Snow Shoe." Wounded in the wrist, he relied on his wife, "Two Kettles Together" to load his musket for him. On the right, advancing from behind the cover of a tree, is a green-coated Loyalist ranger.

What is remarkable about these two protagonists is the expressiveness of their faces. These are individual human beings, swept-up in the terror of war. What sticks in the memory after studying this compelling work is the piercing gaze of the Oneida chief and the stunned awareness of danger of the Loyalist soldier after glimpsing three muskets being aimed at him through the smoke of battle.

After spending quite a long time analyzing Troiani's The Oneida at the Battle of Oriskany, I went and re-examined paintings I had studied earlier. Over and over again, I found that Troiani had invested the characters in these works with the same individualism and psychological depth that made Thawengarakwen, Two Kettles Together and the Loyalist soldier such compelling figures in the Oriskany battle scene. To say that I was impressed is an understatement.

Liberty: Don Troiani's Paintings of the American Revolution is the first retrospective of Troiani's visual narratives of the events of 1775-1783. It is the third major exhibition mounted by the Museum of the American Revolution, brilliantly complementing the permanent exhibits. Troiani and the staff of the Museum of the American Revolution, especially Matthew Skic, Curator of Exhibitions, have indeed filled in the "blank canvas" of these war-torn years in a way that contemporary artists were unable to do.

By capturing the emotional torment, the terrible stress and the personal sacrifice of the Revolutionary War generation, Don Troiani has primed the canvases of his remarkable paintings with the Spirit of Liberty, for which so many fought and for which so many died.

***

Text: Copyright of Ed Voves, all rights reserved. Several photos by Ed Voves are of paintings by Don Troiani © Don Troiani.

Introductory photo: Ed Voves, Photo (2021) Detail of Don Troiani's Artillery of Independence, Siege of Yorktown, Virginia, October 9, 1781. Painted 2013. Oil on Canvas, Private Collection.

Ed Voves, Photo (2021) Don Troiani and curator Matthew Skic (right) at the press preview for Liberty: Don Troiani's Paintings of the American Revolution at the Museum of the American Revolution, Philadelphia. PA.

Paul Revere (1734-1818) The Bloody Massacre perpetrated in King Street, 1770. Hand-colored engraving and etching: 10 1/4 x 9 1/8 in. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Gift of Mrs. Russell Sage, 1910, # 10.125.103

John Singleton Copley (American, 1738-1815. The Death of Major Peirson, 1783. Oil on canvas: 8' 1'' x 12'. Tate Britain. N00733

No comments:

Post a Comment