How Art Can Change Your Life

by Susie Hodge

Thames & Hudson/$19.95/191 pages

While reading Susie Hodge's new book, How Art Can Change Your Life, the lyrics of one of the songs from the 1980's musical, Barnum, came to mind.

Bigger isn't better Taller isn't braver Stronger isn't always wise

Smaller isn't necessarily the lesser Guts can come in any size

The song lyrics were entirely appropriate given the book's surprisingly small size - 191 pages - and the audacious scope of its subject.

How Art Can Change Your Life deals with human emotions and the many challenges to our identity and well-being. Susie Hodge sets herself the daunting task of showing how appreciating great works of art can help address the problematic situations which plant themselves in the path of our journey through life. That took a lot of courage on Hodge's part, a lot of "guts."

How Art Can Change Your Life presents 72 masterpieces of art, mostly paintings, beginning with Giotto's Arena Chapel frescoes and extending to contemporary artists like Yinka Shonibare. These are examined thematically in twelve sections dealing with vital issues such as confronting anxiety, relieving stress, overcoming sorrow, inspiring self-reflection and embracing happiness.

Each of the 72 entries in How Art Can Change Your Life consists of a full-color illustration of the masterpiece and one-page commentary.

Page display from How Art Can Change Your Life, showing Aelbrecht Bouts' The Mater Dolorosa, mid-1490's

The basic format of each text entry begins with an illuminating quote, followed by a succinct artist biography and an analysis of the work. The commentary concludes with a reflection on how understanding the respective masterpiece might help deal with one of the many psychological or spiritual problems we face in the disturbing world of the twenty-first century.

All of these tasks are accomplished on a single page. Like the Wanderer above a Sea of Clouds by Caspar David Friedrich, we need to travel light in the quest of How Art Can Change Your Life.

Hodge begins the book with a short, three page introduction. As readers familiar with the "In Detail" books will know, Hodge is a master of concise, informative prose and an able stylist. In this brief intro, she incorporates moving quotes from some of the artists whose works are later analyzed. She follows with findings from scientific studies on the cognitive and emotional effects of looking at art and then sets the stage for the bold venture into art appreciation in the succeeding pages.

Yet, at the starting gate, Hodge almost stumbles. The first topic she deals with is the most difficult: dissipating anger. Hodge deserves credit for her sincere attempt to provide constructive channels for anger management. But to try and get a "grip" on explosive human emotions in six brief art critiques is to risk falling back on formulaic responses or suggestions, such as the following:

Feelings of anger can be reduced or neutralized by making a list of things to be grateful for, or focusing on what is good in life.

This is quite sensible advice and, from the standpoint of anger prevention, it is wise counsel indeed. But once the flashpoint of anger is reached, I doubt that Hodge's good intentions will be of much help.

Moreover, two of Hodge's choices of art works to be examined in conjunction with anger are very problematical. Pipilotti Rist's car-window smashing video, Ever is Over All, seems an act of fomenting violence or enjoying it vicariously. Whatever Rist's motives in making her protest in defiance of modern mechanized society, its inclusion in How Art Can Change Your Life strikes me as inappropriate to the goals of the book.

The other unsettling work of art is so famous and controversial - especially in the last few decades - that an entire book might not be enough to it justice. This is Artemesia Gentileschi's Judith Beheading Holofernes, painted around 1620.

If ever an artist had a right to be angry or to try and vent her rage with a powerful work of art such as this, it was Artemisia Gentileschi (1593-c.1656). Yet, her life's meaning is not to be comprehended by concentrating on this painting at the expense of the rest of her oeuvre.

After being raped by her father's colleague and then outrageously abused by the legal tribunal investigating the crime, Gentileschi went on to paint other masterpieces, which are sadly less familiar than this one. Judith Beheading Holofernes appears over-and-over in art history books.

Thus, Gentileschi's story illustrates Hodge's theme of utilizing art to overcome anguish or anger. But the inclusion of this celebrated depiction of violence detracts from grasping that point. It would have been far more in keeping with the spirit of How Art Can Change Your Life to have used one of Gentileschi's later works, notably her moving, visionary self-portrait now in the Royal Collection in Great Britain.

Once Hodge moves beyond the contested ground of anger-dissipation, How Art Can Change Your Life is on firmer ground. That does not mean that Hodge avoids dangerous or difficult situations to rack-up debating points in support of her thesis. Throughout this fine book, Hodge looks at great works of art in conjunction with many of history's most harrowing ordeals.

With keen insight, Hodge reminds us that Claude Monet could hear the barrages of World War I artillery as he worked to depict the effect of light and shadow on the lily pond and gardens of his private paradise of Giverny.

Through all the turmoil of war, Monet waged his own private battles, as well, contending with family loss, cataracts and old age. In doing so, Monet "created a sense of peace around him...This enabled him to reset and overcome his anxiety."

Like Monet, Paul Klee used his art as a shield against stress, in his case of the most direct and oppressive form. Driven from his teaching position at the Dusseldorf Academy by Nazi aggression, Klee created his own, interior Giverny. During the last years of his life, Klee painted over 1,000 works of art, each an affirmation of the creative spirit vs. the soulless mindset of totalitarianism.

Klee's response to adversity is a process available to us too, as Hodge notes :

...Klee was a Transcendentalist, and one aspect of transcendentalist belief is that the material world is only one of several realities and that creativity comes from beyond consciousness. Klee used the process of making art as meditation, saying that it helped him live in an "intermediate world."

This is precisely the situation of millions of people today, shadowed by the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic and the growing fear of global warfare.

Hodge continues her reflections on Klee with a discussion of Post-Traumatic Growth through which "people who have suffered extreme stress use the experience to enhance and appreciate life and also learn to embrace new opportunities..."

This is a brilliant illustration of Hodge's skillful pairing of incisive art analysis with thoughtful suggestions for life-enhancing activities.

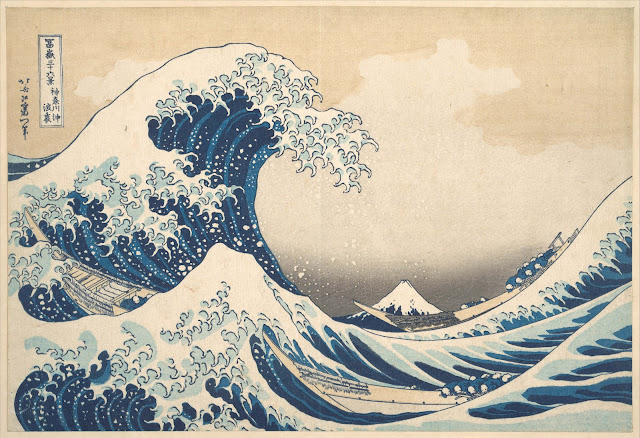

Many of the art works Hodge selected are "old friends" from museum visits or hours spent leafing through exhibition catalogs. Hokusai's Under the Wave off Kanagawa appears in the topical section on "creating energy." It is a curious placement, given that Hodge envisions this fabled work as a "vision of human fragility and defencelessness..."

Energy is the keynote of Under the Wave off Kanagawa - of nature and of humankind. When your boat is about to be swamped - literally or metaphorically - you row all the harder. And you create all the more. Claude Debussy (1862-1918) composed LeMer (1903-05) with the imagery of Hokusai's masterpiece ever in his mind.

The Annunciation by Henry Ossawa Tanner (1859-1937) is another work studied in How Art Can Change Your Life. It is one of the highlights of the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. I am fortunate to see this work frequently and I never cease to be amazed and inspired.

The Annunciation, in which the Virgin Mary is informed by the Angel Gabriel that she will be the mother of Jesus, is one of the most ancient subjects of Christian art. Here Tanner re-envisions the sacred scene in terms of startling, psychological drama. Gabriel appears as "pillar" of fire, pure energy rather than a humanized form. Mary, is surrounded by bands of deep, rich color, These represent a fabric screen, rugs and blankets but exert a similar effect to the ethereal color blocks of Mark Rothko.

All of this visual alchemy took place in 1898, years before the radical stages of Modern Art began. Yet the most revolutionary feature of Tanner's Annunciation - and the reason it appears in Hodge's section on empathy - is that Tanner depicted Mary as Jewish girl with dark Middle Eastern ethnic features at a time when Jews were facing racial and religious prejudice.

It was a bold step - but one based on personal experience. Tanner was an African-American artist who, as a student, had experienced discrimination himself. Fortunately, Tanner became the protege of Thomas Eakins and received support from Rodman Wanamaker, of the famous department store fortune. None-the-less, Tanner was risking the esteem of his White patrons by painting the Virgin Mary as a young Jewish woman.

Choosing Henry Ossawa Tanner's Annunciation was a masterstroke on the part of Hodge. Just as The Annunciation is an example of empathy in action, so too is How Art Can Change Your Life.

One could - and should - treat Susie Hodge's How Art Can Change Your Life as a "tract for the times." But given the genuine worth of this inspiring, provocative volume, it will, I believe, prove a "ready-reference" book to be consulted and cherished for a long time to come.

***

Text: Copyright of Ed Voves, all rights reserved Original Photos: Copyright of Anne Lloyd

Cover art and page display from How Art Can Change Your Life © Thames & Hudson

Introductory Image: Caspar David Friedrich (German, 1774-1840) Wanderer above the Sea of Fog, c. 1818. Oil on canvas: 94.8 cm × 74.8 cm (37.3 in × 29.4 in.) Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg

Artemesia Gentileschi (Italian, (1593-c.1656) Judith Beheading Holofernes, c. 1620. Oil on canvas: 146.5 cm × 108 cm (57 2/3 × 42 1/2 in.) Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence, Italy

Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926) The Japanese Footbridge, 1899. Oil on canvas: 81.3 cm × 101.6 cm (32 × 40 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Paul Klee (Swiss-German, 1879-1940) Red Balloon,1922. Oil on gauze on board: 31.7 cm × 31 cm (12 1/2 × 12 1/4 in.) Guggenheim Museum, New York City.

Katsushika Hokusai (Japanese, 1760-1849)Under the Wave off Kanagawa, c. 1830-32. Woodblock print; ink and color on paper: 25.7 cm × 37.9 cm (10 1/8 × 15 in.) Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

No comments:

Post a Comment