Hidden Faces: Covered Portraits in the Renaissance

Metropolitan Museum of Art

April 2, 2024 - July 7, 2024

Reviewed by Ed Voves

On June 9, 1311, the populace of the Italian city-state of Siena celebrated the installation of a magnificent altarpiece in the city’s cathedral. Trumpeters, pipers and a lone castanet player led a throng of citizens and clergy to see the dazzling new work of Christian art.

Created by Duccio di Buonisegna, this altarpiece, known as the Maesta, is dominated by a towering, 14-foot high likeness of the Virgin Mary. Surrounding Mary is a retinue of angels and saints, each depicted with reverence and discernment.Yet, there is a baffling omission among this heavenly host.

Except as a young child cradled on the lap of his mother, Jesus is nowhere to be seen!

Duccio di Buonsegna, Maesta (main alter panel), 1308-1311

Appearances are deceiving. The Maesta actually had numerous painted images of Jesus. But these were placed on wooden panels on the back of the altarpiece, blocked from the sight of the congregation.

Why the mystery? Why conceal scenes from the life of Jesus from devout Christians in one of the premier churches of Christendom?

The answer, for the Maesta and for many other Renaissance paintings, involves grasping a mindset fundamentally different from that of our times. Cultivating an air of mystery and mysticism, expressing issues and ideals through the agency of allegory, this is how the Renaissance mind dealt with matters, both sacred and profane.

A brilliant new exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Hidden Faces: Covered Portraits in the Renaissance, investigates the practice of creating works of art that were both inspiring and cryptic - by design.

Embellished with symbolism drawn from Christian scripture and Classical myths, these painted portraits were often mounted behind decorated covers and screens.

Suo Cuique Persona. Taken from ancient Roman texts, the inscription reads "to each his own mask."

On the backs of many of these these portraits were more examples of message-coded imagery - a family coat of arms, a personal motto, sometimes faux images of precious materials like marble or porphyry. One of the most significant portraits in Hidden Faces displays a skillful rendition of a vase of flowers, the earliest still life in European painting.

Most of the works of art on view in Hidden Faces are portraits painted in oils, the great technical innovation of the Renaissance in northern Europe. Among the exceptions is a pair of carved wooden canisters showing the faces of Friedrich the Wise (1461-1525) and his mistress, Anna Rasper (above). These are believed to based upon sketches by Albrecht Durer.

The real standout among the unconventional treasures of Hidden Faces Is a small, wooden devotional shrine. It comes from the German province of Swabia, 1490.

Distinctly medieval in appearance, this triptych is a rare work, one of the treasures of The Met's Cloisters collection. Surviving the centuries intact, it perfectly illustrates how religious images were kept behind "closed doors" for most of the time. Then for prayer sessions or holy days, the doors would be opened.

In some cases, clever design features of the frames holding the paintings added new meaning to the proverb, "beauty is in the eye of the beholder."

An Italian mirror frame, carved in the shape of a tabernacle during the mid-1500's, appears at first sight to be one of the more prosaic objects on view in the Hidden Faces galleries. But an accompanying video loop documents how, by pulling on sliding shutters, two concealed images would be revealed.

The first is an allegory, based on Michelangelo's The Dream, while lurking below is the real object of devotion, the image of a "lady love."

Was this a case of playing coy, erotic parlor games or something more serious? At its most profound, Hidden Faces reveals the power of images

during the Renaissance as something so potent that each needed to be accorded special recognition and treatment.

Hidden Faces tells the story of little known, arcane aspects of the Renaissance, rescued from history's footnotes. For this we have to thank the lead curator, Alison Manges Nogueria, for her outstanding research and organizational skills.

To untangle the often obscure details of the fascinating works of art presented in Hidden Faces, Nogueria and her colleagues have followed the wise policy of the scholars who studied the Maesta. The Met curators have paid as much attention to the backs of these Renaissance paintings, as they did to the portraits painted on their fronts.

The portrait, Francesco

d’Este, created by Rogier van der Weyden and assistants, ca. 1460, exemplifies the continuing importance of heraldry and other badges of aristocratic power and privilege.

The identity of the sitter for this portrait took considerable scholarship to confirm. The coat of arms painted on the reverse showed that he was a member of the noble house of D'Este from northern Italy. That was the easy part of the process.

The confusing point was the presence of lynxes among the heraldic symbols, a deliberate feline reference to "Leo" in the name Leonello. This clearly makes the coat of arms that of Leonello d'Este, Marquess of Ferrara (1407-1450). Yet, historical detective work ultimately resolved that the portrait was of Francesco d'Este, the illegitimate son of Leonello.

With a compromised pedigree, Francesco d'Este was apprenticed to serve as a soldier to the powerful Duchy of Burgundy, the celebrated stronghold of Chivalry and rival power base to the court of the kings of France. The dukes of Burgundy were leading patrons of the "new art," especially Flemish painters like Jan van Eyck and Roger van der Weyden.

The Burgundian army in which Francesco d'Este served was top-heavy with armored cavalry. At the Battle of Grandson in 1476, the arrogant Burgundian knights attacked a force of tough, pike-wielding Swiss foot soldiers. The result was an unmitigated disaster for the Duchy of Burgundy and the ideals of Chivalry.

Johann von Ruckingen, somehow, did not learn that lesson, until bitter experience taught him otherwise.

Johann von Ruckingen was a prosperous merchant from Frankfurt, Germany, ennobled in 1468. In 1487, he made a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, then a dangerous undertaking. While there, he joined two chivalric orders, the Order of the Holy Sepulcher and the Cyprian Order of the Sword.

The insignia of the two chivalric orders were added to the frame of von Ruckingen's portrait. This had been painted in April 1487 just before he left for the Holy Land. Von Ruckingen's portrait formed one side of a diptych, the other no doubt bearing the likeness of his wife, Agnes.

Von Ruckingen must have thought he had joined the top tier of German society after surviving his trip to Jerusalem. He began to dress in extravagant fashion, violating the sumptuary laws. These rules restricted the degrees of color and style for clothing and quality of cloth, fur and jewelry according to rank. Von Ruckingen exceeded the dress code allowed to his level of nobility and was imprisoned until he relented.

Perhaps a key to von Ruckingen's rash behavior can be found on the reverse of his portrait. There we see his coat of arms, with a Wild Man lurking behind it.

The Wild Man was a heraldic motif used in numerous European cultures. For a nobleman, whose family tree had roots in the ancient past, the Wild Man may have been an appropriate symbol. For a very new and junior member of the nobility like Johann von Ruckingen to make use of the Wild Man seems a reckless and foolhardy thing to do.

With the third portrait selected for our analysis, Hans Memling's Portrait of a Young Man, we lack the most basic item of information: his name.

Yet, there is much to be discerned from closely studying this work. For example, the young man's clothing and hair style are clues that he was a member of the Italian mercantile community in Bruges. These bankers and cloth merchants were important clients for Memling. The Italians knew talent when they saw it and Hans Memling was one of the premier painters of his era.

Intelligent guesswork and careful scholarship have enabled us to to come close to fully appreciating this brilliant work by Memling, even without a positive ID of its subject. But the most intriguing detail, painted on the reverse of the portrait, remains tantalizingly just beyond our grasp.

Here we see a glazed majolica jug, filled with flowers and displayed on a richly-tectured table cloth. Scholars believe that this is the first still life in art history, making it a very significant work of art.

The people for whom Memling painted this "still iife" would not have understood the concept at all. The jug is inscribed IHS, the monogram of Jesus. The flowers it holds symbolize key religious ideals related to the mother of Jesus: the lilies represent Mary's purity, the irises proclaim her as the Queen of Heaven and mater dolorosa, the "mother of sorrow." The very small flowers are aquilegias, associated with the Holy Spirit. And the table cloth was woven with the motif of stylized crosses.

Memling's "still life" is composed in the setting of a devotional altar. When the diptych or triptych was closed, this was the image which would have been seen. Unlike the shimmering gold and costly pigments used by Duccio to create the Maesta, all the artifacts depicted are common, almost "humdrum", objects of everyday life. It is a heavenly vision brought down to a family living room.

The early Renaissance was the age of devout groups of Christians such as the Brethren of the Common Life, the Beguines, the Gottesfreunde or Friends of God. Their religious lives centered on the Devotio Moderna, a form of Christianity founded upon meditation, mysticism and charitable deeds.

For the most part, these “friends of God” were middle-class people living in Flanders, Holland and the Rhineland. But Italian merchants in these regions, like Memling’s praying man, would have known them well. And what is more, some may have joined them.

The shift from public religious ritual to an emphasis on personal spirituality led in time to Martin Luther and the Reformation. Many of the features of medieval art and Christian liturgical practice, which are brilliantly examined in this Met exhibit, were discarded or "reformed" away.

As artistic conventions changed in response to the Protestant Reformation and to the Catholic Counter-Reformation, portrait painting increasingly favored realism over symbolism, emotions over allegory.

When the features of Renaissance worthies were brought to life by masters like Raphael and Titan, there was no need to resort to a code of arcane imagery to illustrate or define human character traits. Portrait painters became ever more skillful in depicting the facial features of their subjects and, in the process, increasingly proficient in probing the secrets of their souls.

By the time of the emergence of Caravaggio at the end of the Renaissance, a great artistic revolution had transpired. Once locked away behind wooden covers and interpreted through cryptic symbolism, portrait painting now spoke with a voice - and a vision - of its own.

***

Text: Copyright of Ed Voves, all rights reserved

Introductory Image: Ed Voves, Photo (2024 Ridolfo Ghirlandaio‘s Cover with a Mask, Grotteschi, and Inscription (detail), ca. 1510.

Duccio di Buonisegna (Italian, 1255-1319) Maesta, 1308-1311. Tempera and gold on wood: 84 x 156 in. (213 x 396 cm.) Museo dell'Opera del Duomo, Siena, Italy https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Duccio_maesta1021.jpg

Ed Voves, Photo (2024) Gallery view of the Hidden Faces exhibition at the

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Ed Voves, Photo (2024) Ridolfo Ghirlandaio‘s Cover with a Mask, Grotteschi, and Inscription, ca. 1510.Oil on panel: 28 3/4 × 19 7/8 in. (73 × 50.5

cm). Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence, Italy

Ed Voves, Photo (2024) Ridolfo Ghirlandaio’s Portrait of a Woman (La Monaca), ca. 1510. Oil on wood panel: 25 9/16 × 18 15/16 in. (65 × 48.1 cm) Gallerie degli Uffizi,

Florence, Italy

Ed Voves, Photo (2024) Gallery view of the

Hidden Faces exhibition, showing a carved wooden canister by Meister der

Dosenkopke, 1525.

Unknown German Sculptor from Swabia.

House Altarpiece (triptych

showing St. Anne, the Virgin Mary, the Christ Child and various saints), ca.

1490. Oil and gold on wood; metal fixtures: Overall (open): 13 3/16 × 11 7/8 × 2 15/16 in.

(33.5 × 30.2 × 7.5 cm)The Metropolitan Museum of Art,

Cloisters Collection, #1991.10

Ed Voves, Photo (2024) Tabernacle Mirror Frame,

Ferrara, Italy, 1540-60. Walnut: Overall: 16 5/16 × 15 3/16 in.

(41.5 × 38.5 cm) The Metropolitan Museum of Art,

Robert Lehman Collection, #1975.1.2090

Ed Voves, Photo (2024) Sequence of video images, showing the operation of the Tabernacle Mirror Frame (above) and hidden images. Video presentation created by the Metropolitan Museum of Art staff.

Ed Voves,

Photo (2024) Hans

Memling’s Allegory of Chasitity (cover for a lost portrait?), 1479-1480.

Ed Voves,

Photo (2024) Gallery view of the Hidden

Faces exhibition showing Metropolitan Museum curator, Alison Manges

Noguera.

Ed Voves,

Photo (2024) Gallery view of the Hidden

Faces exhibition, showing Hans Memling's Portrait of a Man in a two-sided display frame.

Ed Voves, Photo (2024) Rogier van der Weyden’s Francesco

d’Este, ca. 1460.

Ed Voves, Photo (2024) Reverse of Francesco

d’Este, by Rogier van der Weyden and assistants, showing detail of coat of

arms.

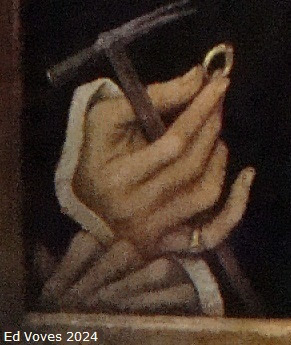

Ed Voves, Photo (2024) Rogier van der Weyden’s Francesco d’Este, ca. 1460 (detail of jousting hammer, ring)

Ed Voves, Photo (2024) Reverse of Francesco d’Este, showing of d’Este coat of arms.

Ed Voves (2024) Portrait of Johann von Ruckingen, 1487, by

Ed Voves (2024) Wolfgang Beurer's Wildman with von Ruckingen Coat of Arms, verso of above.

Hans Memling (Netherlandish, active by 1465–died 1494 ) Portrait of a Man (recto); Flowers in a Vase (verso), 1485. Oil on panel: 11 1/2 × 8 7/8 in. (29.2 × 22.5 cm) Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid (284.a (1938.1.a); 284b (1938.1.b))

Ed

Voves, Photo (2024) Jacometto

Veneziano’s Portrait of a Boy, ca.

1475-80. Tempera and oil on wood panel: 9 × 7 3/4 in. (22.9 × 19.7 cm). National Gallery, London.

No comments:

Post a Comment