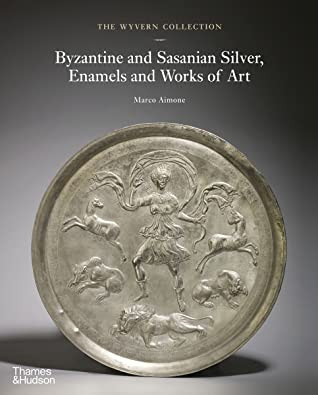

The Wyvern Collection:

Byzantine and Sasanian Silver, Enamels & Works of Art

By Marco Aimone

Thames & Hudson/$95/552 pages

Reviewed by Ed Voves

The Eastern Roman Empire, or Byzantium, survived the fall of its western partner in 476 by almost a thousand years. Despite the amazing tenacity of the Byzantine emperors, Edward Gibbon characterized the history of their realm as “a tedious and uniform tale of weakness and misery.”

Gibbon was a scrupulous scholar but had limited access to the astonishing works of art created in the Byzantine dominions. Many of these were only discovered long after Gibbon finished writing The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Had Gibbon been able to study the magnificent new volume of the Wyvern Collection series, he would likely have modified his negative estimate of the "weak" and "miserable" successor of Imperial Rome.

The Wyvern Collection: Byzantine and Sasanian Silver, Enamels and Works of Art is the third volume to analyze a private collection whose works of art are rarely displayed in museum exhibitions. Published by Thames & Hudson, this latest book enables us to grasp the broad range of the Wyvern collection. The earlier volumes dealt almost exclusively with the art of the medieval West and I mistakenly stated in my first review that "the Wyvern collection has only a few works of art from the Byzantine Empire."

I stand corrected.

Volume III of the Wyvern series provides insight on stunning Byzantine art works, dating from Late Antiquity to the time of the Crusades. These masterpieces refute any remaining misconceptions of Byzantium as "weak" and "miserable."

Page spread from The Wyvern Collection: Byzantine and Sasani

an Silver, showing Plate with a horse & rider attacked by a lioness, 12th century.

©The Wyvern Collection &Thames & Hudson, Ltd.

Not only were the high standards of ancient culture preserved by the artists of the Byzantine Empire, but many of the brilliant works of art discussed in this magnificent book reveal an unprecedented upsurge in spirituality, the Christian Revolution.

Byzantium, based on its capital city of Constantinople, was a Christian empire. The conversion of the Roman emperor, Constantine I (272-337) to Christianity decisively shifted the religious orientation of the Roman Empire eastward. There, in Syria and in Egypt, Christianity had been embraced by ever-growing numbers of the populace, especially in leading cities like Antioch and Alexandria.

Perhaps the key work of art of the entire book is the Processional Cross, made in the mid-eleventh century. It is a Latin-style cross with five roundel images on each side. Those on the front were gilded, with the icon of Christ Pantokrator (cosmic ruler) in the center. The reverse side features images created in the niello process. Mary, the mother of Jesus, occupies the central placement. Mary is depicted in the Virgin Hodegetria pose, "She Who Points the Way."

Throughout the book, we see this Latin cross in many forms, a cross from a book binding, a reliquary cross, a cross engraved in the center of a Eucharistic dish or paten. All testify to one of the supreme events of Christian history, the crucifixion of Jesus, and to a moment of high political drama, as well. This was the Battle of Milvian Bridge, October 28, 312. Just prior to the battle against a rival for the Imperial throne, Constantine saw the shape of such a cross in the sky, accompanied by the words, "In this sign, conquer!"

Up to that point, Constantine had shown little interest in the Christian religion. Yet, something mystical must have happened. Constantine heeded the vision and went on to win the battle. The victory set the stage for his eventual conversion to Christianity, which Byzantine artists never ceased depicting.

I had the good fortune to be able to study a similar cross, The Adrianople Cross, from the Benaki Museum in Athens. This inspiring object was positioned at the entrance to the 2013 Heaven and Earth exhibition at the National Gallery in Washington D.C. It was an unforgettable moment, underscoring the importance of art to religious belief - and vice versa.

A counterpart to the Adrianople Cross and the Processional Cross, shown above, will be familiar to art lovers who have seen or studied the mosaic of the Emperor Justinian and Archbishop Maximian in the church of San Vitale in Ravenna, Italy. Indeed, examples of the other objects depicted in this famous scene - the glittering presentation vessel carried by Justinian, the incense-burning censor held by a clergyman in the retinue - are analyzed in considerable detail in this new volume of the Wyvern series.

Detail of the mosaic of The Emperor Justinian and His Retinue,

from the Church of San Vitale, Ravenna, c. 547

If many of the objects in the Wyvern Collection bring to mind similar works of art displayed in museums, others are less familiar and indeed are "wondrous strange." None fits this description better than the Enkolpion of Constantinos.

Created around the same time as the Processional Cross, the Enkolpion of Constantinos was a small devotional object, measuring 7.1 x 5.9 cm (approximately 3 inches by 2.5 inches). Suspended on a thin chain around the neck, it was worn over the chest. There are other enkolpions studied in the present volume which were carved as single images, just like a religious medal today. Not so, the Enkolpion of Constantinos!

The Enkolpion of Constantinos, 11th century.

©The Wyvern Collection &Thames & Hudson, Ltd.

The Enkolpion of Constantinos opens to form a miniature triptych. It measures 11.4 cm or 4 1/2 inches in width. Two side panels show Christian saints and a central scene (shown above) portrays a Byzantine emperor worshiping at the feet of Christ Pantokrator. In essence, this enkolpion is a miniature altar piece. It is a small wonder indeed!

The Wyvern Collection: Byzantine and Sasanian Silver, Enamels and Works of Art is a wonder too, though hardly a small one. It is splendidly illustrated, authoritative in its analysis and - within the parameters of scholarly writing - very readable. The main text was written by Italian scholar, Marco Aimone, a senior curator for the Wyvern Collection. A supplemental essay on Byzantine enameling technique was provided by Jack Ogden. This, by every standard, is a definitive examination of one of the most sensational of all Byzantine art forms.

As the title of the book proclaims, works of art from the great rival of early Byzantium, the Sasanian Persian Empire, are also studied. Although ever bit as accomplished as those of Byzantium, these Sasanian art works were backward-looking in theme. The hunting scenes are a deliberate throwback to ancient Persian, indeed Assyrian, art. The more sensual motifs, likewise, recall Hellenistic Greek art. The same applied to much late-Roman art, also examined in this book.

Byzantine art was much more dynamic - an accolade seldom given to this reputably "static" civilization. Byzantine art is moving art. Byzantine art, including icons, moves our minds, our hearts, our souls in transcendent directions.

This bronze vessel, with silver inlay from the beginning of the Byzantine period, might represent the Holy Spirit or may be just a dove. It might have served a liturgical purpose or functioned as an unguentaria, a cosmetic receptacle. The superb naturalism of its form serves either purpose and succeeds so brilliantly that our imaginations take flight just looking at it!

What better comment or praise can we give to wonderful works of art, such as these, or to the mighty volume which presents them to us? Though hardly bed-side reading, The Wyvern Collection: Byzantine and Sasanian Silver, Enamels and Artwork is a worthy successor to the earlier volumes. It is a book to be cherished, a feast for the eyes and the intellect and balm for the soul.

***

Text: Copyright of Ed Voves, all rights reserved

Images from: The Wyvern Collection: Byzantine and Sasanian Silver, Enamels and Artwork © 2020 The Wyvern Collection, Design and layout © 2020 Thames & Hudson Ltd, London

The Emperopr Justinian and His Retinue; detail of mosaic from the left side (north wall) of the apse, San Vitale, Ravenna, Italy. Courtesy of the University of Michigan - Art Images for College Teaching. EC251

No comments:

Post a Comment