Crafting the Ballets Russes: Music, Dance, Design

The Robert Owen Lehman Collection

The Morgan Library and Museum

June 28 - September 22, 2024

Reviewed by Ed Voves

Original Photography by Anne Lloyd

Looking back over the ballet scene during the first half of the twentieth century, Igor Stravinsky wrote an essay in the November 1953 issue of Atlantic Magazine. Stravinsky recalled the "impressive figure of a man" who "by sheer inspiring energy and breath of cultural initiative, raised the prestige of the ballet to undreamed of heights."

With these words, Stravinsky summoned to life the memory of Sergei Diaghilev, master-mind and dynamic leader of the incomparable Ballet Russes.

A recently-opened exhibition at the Morgan Library and Museum, Crafting the Ballet Russes, brilliantly illustrates the story of the legendary ballet company with a treasure store of documents, artifacts and pictures. Yet, it is important to note that the Morgan exhibit surveys the same cultural "landscape" as Stravinsky's essay from a different vantage point.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024)

Gallery view of Crafting the Ballet Russes at the Morgan Library

Instead of focusing on Diaghilev's life and leadership, the Morgan exhibition directs our attention to the actual manuscripts of the musical scores he commissioned for the Ballet Russes. These remarkable scores, composed by Stravinsky, Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel come from the Robert Owen Lehman collection which has been on deposit at the Morgan for over half a century. Occasionally one of these hand-written and annotated scores is displayed as a "treasure from the vault" at the Morgan. But this exhibition is one of the rare occasions when a number of these scores have been placed on display, en masse.

Prelude a l’apres-midi d’ un faune, 1894. Autograph manuscript.

Robert Lehman Collection, Morgan Library

Vaslav Nijinsky

Choreographic notes, Afternoon of a Faun, ca. 1913-1915

Music and dance, thus, take precedence over personal celebrity in Crafting the Ballet Russes. This is a decision which Diaghilev would certainly have approved. Moreover, the Morgan exhibition emphasizes the contributions of the group of talented dancers, musicians and artists who made the Ballet Russes such a success rather than emphasizing the role of their leader.

This "from the many, one" approach to telling the Ballet Russes story complicates the curator's tasks in managing the narrative sequence. There is a lot to cover in Crafting Ballet Russes and the danger of information overload for the non-specialist visitor is very real. Additionally, there are the inherent difficulties of addressing music and dance in an art exhibition.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024)

Robinson McClellan, curator of Crafting the Ballet Russes

The curator of Crafting the Ballet Russes, Robinson McClellan, is the Morgan's Associate curator of Music Manuscripts and Printed Music. His knowledge and passion for his subject were demonstrated in an outstanding lecture he presented on the opening day of the exhibition. Very wisely, McClellan opted for a chronological approach for presenting the Ballet Russes saga, cleverly integrating the precious Lehman manuscripts with the mass of other historic material.

In one especially brilliant move, iconic photos of Nilinsky performing Afternoon of the Faun are matched to the musical notation of the score for several moments in the ballet.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024)

Gallery view of Crafting the Ballet Russes, showing Adolf de Meyer's photos of Vaslav Nijinsky in Afternoon of a Faun. 1912

Below the photos, Debussy's original version of the score is contrasted with Nijinsky's revisions for his dance choreography. Illustrated here is Measure 91, where the faun, having taken-hold of the nymph's veil, arches his back and begins to laugh.

Anne Lloyd (photos, 2024)

Debussy's original notation of Measure 91 of Afternoon of a Faun (top) and Nijinsky's chorographic revisions (below)

As the story of the Ballet Russes unfolds in the Morgan exhibit, the achievements of the protagonists in this incredible moment of cultural history receive their just due. Not surprisingly, Igor Stravinsky exerts a powerful presence in the exhibition.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024)

Pablo Picasso’s Portrait of Igor Stravinsky, 1920

Stravinsky, a composer of prodigious musical gifts, studied orchestration under the great Rimsky-Korsakov. Diaghilev spotted Stravinsky early, commissioning him to compose the score of The Firebird (1910) while others doubted if the inexperienced, though talented, young man was a good "fit" for the ballet.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024)

Igor Stravinsky’s “Adagio / Supplication of the Firebird” from Firebird

Autograph manuscript. Lehman Collection, Morgan Library

Stravinsky responded to Diaghilev's vote of confidence with a devotion that was still evident in his Atlantic essay four decades later. It is fascinating to study the score of Rite of Spring (in this case a remarkable facsimile) with a note scrawled in colored pencil, recalling how Stravinsky had suffered from a raging toothache as he labored to finish composing it.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024)

Igor Stravinsky‘s Rite of Spring, Sketches, 1911–1913 (Facsimile)

There is a rich selection of photos, works of art and memorabilia related to other Ballet Russes luminaries, Tamara Karsivina, Vaslav Nijinsky and his sister Bronislava Nijinska, Ida Rubinstein, Leon Bakst and Michel Fokine.

Tamara Karsavina and Michel Fokine in Firebird, 1910

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024)

Vaslav Nijinsky and Bronislava Nijinska in Afternoon of a Faun, 1912

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024) From left, a postcard of Vaslav Nijinsky, ca. 1908, & an autographed note from Nijinsky, reading “Let us dance, let us pray, let us make love.”

The galleries of Crafting the Ballet Russes are like a time-capsule. Almost without exception, the works of art and artifacts on view date from the 1909-1929 heyday of the dance company. Many were used to prepare and publicize the ballet "seasons" rather than serve as objects d' art. The exception is the bronze cast of a sculpted sketch of Nijinsky which Rodin made after attending the 1912 premier of Afternoon of the Faun. This loan from the Met provides a marvelous center point for the Morgan exhibition.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024

Auguste Rodin’s Vaslav Nijinsky in The Afternoon of a Faun

For lovers of art, music and dance, Crafting the Ballet Russes is an embarrassment of riches. Another important feature of the exhibition is the special attention given to the role of women in the dance company. The role of Bronislava Nijinska, who became the lead choreographer for the company in 1921, and the art work of Natalie Goncharova, are specially noteworthy.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024) Bronislava Nijinska in 1921

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024)

Self-portrait of Natalia Goncharova, ca.1907

With all of the well-deserved attention to the Ballet Russes roster of genius, Diaghilev, himself, remains largely an off-stage presence in the Morgan exhibition. Yet, his role was central to the success of the Ballet Russes throughout the twenty-year span of its existence.

A brief look at the history of that era underscores Diaghilev's importance..

After Russia's shocking defeat in the 1904-1905 war with Japan and the ensuing outbreak of riots and domestic insurgency, Diaghilev conceived a cultural "charm offensive" to restore the prestige of the Tsarist empire. Diaghilev was a fervent proponent of "gesamtkunstwerk." Music, dance, elaborate stage effects, every genre of the visual arts, including motifs from ancient times - all were combined to create a "total work of art."

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024)

Souvenir program for the Ballet Russes, 1911, Theatre du Chatelet

Richard Wagner has raised Germanic culture to sensational levels of international acclaim by such means. Diaghilev believed that he could do the same for Russia, organizing and leading music and dance companies and art exhibitions on tours of cities in Western Europe, Britain and the U.S.

Initially, Diaghilev presented several programs of Western-style ballet, superbly danced by members of Russia's Imperial Ballet. European audiences were politely bored, but in 1908 Diaghilev's spectacular production of the opera, Boris Godunov, staring Fyodor Chaliapan, took Paris by storm.

Diaghilev had hit the "gesamtkunstwerk" target right on the mark. Western audiences craved the "exotic." The colorful past of Russia, clothed (or scantily clad) in the garb of the sensuous east, provided a ready supply of source material for future triumphs.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024)

Detail of Natalia Goncharova's Set Design for Les Noces, 1915

Then came a sudden reversal of fortune. Instead of providing additional funding for creating new musical productions evoking Russian culture, the Tsarist government ceased all financial support for Diaghilev's endeavors in March 1909. It was an incalculable blunder that would have brought the effort to raise Russia's artistic profile to a jarring halt - except for Diaghilev's strength of will.

Stravinsky described Diaghilev as a barin, a Russian term difficult to translate. Enlightened despot comes closest to the original meaning.

The barin is by "nature generous, strong and capricious, with intense will, a strong sense of contrasts and deep ancestral roots."

Diaghilev, according to Stravinsky, also possessed a "will of iron, tenacity, an almost superhuman resistance and a passion to fight to overcome the almost insurmountable obstacles."

With this quiver of personal attributes at his disposal, Diaghilev launched the Ballet Russes crusade in 1909. He had little else to rely on, as his personal funds were quickly exhausted. The Ballet Russes operated on a financial tightrope for the entire twenty years of its existence, with Diaghilev's charisma and determination overcoming one "insurmountable obstacle" after another.

Charisma and determination are difficult to illustrate in an art exhibition. But there is an additional reason for the paucity of pictures and memorabilia relating to Diaghilev in Crafting the Ballet Russes.

In 1914, a young Russian artist, Mikhail Larionov (1882-1964) joined the Ballet Russes team. For the next fifteen years, the talented and temperamental Larionov worked for Diaghilev. Disputes and arguments were many, but Larionov greatly admired Diaghilev.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024)

Mikhail Larionov’s sketch of Sergei Diaghilev,

Igor Stravinsky, and Sergey Prokofiev, ca.1918

In 1915-1916, Larionov executed a series of evocative sketches of Diaghilev which provide an intimate portrayal of the "barin" and his henchmen at work. One of Larionov's drawings, now in the collection of the Harvard, is on view in the Morgan exhibit.

The remainder of Larionov's sketches, along with the manuscript of a biography of Diaghilev which Larionov wrote and illustrated, were bequeathed to the Tretyakov Museum in Moscow. (The biography, a fascinating blend of fact and fable, was not published until after Larionov's death.) Because of the strained relations between the U.S. and Russia in recent times, this valuable archive is unavailable for loans to museums in America.

We should not bemoan this loss, unduly. Instead, we should savor what the Morgan is sharing with us in the crowded galleries of the exhibition.

Along with the Lehman Collection manuscript scores, the Morgan has displayed the visual remains of one of the great moments of creativity in the history of art. While there are no actual ballet costumes on view, as were featured in the National Gallery of Art's 2013 Ballet Russes exhibition, the array of photos, costume and set designs and posters is truly spectacular.

Crafting the Ballet Russes charts the course of Diaghilev's bold venture to restore Tsarist Russia's cultural reputation in the eyes of the world. From Schéhérazade, danced to music by Rimsky-Korsakov, to Firebird and Petruschka, the early masterpieces of Igor Stravinsky, to the controversial Rite of Spring, the Ballet Russes astonished (and sometimes outraged) the world.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024)

Detail of Leon Bakst's set design for Schéhérazade, 1910

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024)

Costume design for Firebird (L’Oiseau de Feu) by Leon Bakst, 1910

Vaslav Nijinsky as Petrouchka, 1911

Like the ill-fate puppet, Petruschka, Diaghilev was doomed to fail in his attempt to save Russia from its own folly. But in the course of his effort, Diaghilev the barin and his Ballet Russes artists opened a path to new realms of spirit and the imagination.

The Morgan Library & Museum exhibition is a fitting valedictory for Diaghilev's Ballet Russes as a historical phenomenon. But as one watches videos of the great ballets in the hallway near the entrance of Crafting the Ballets Russes, one soon enters into the "now" moment of the Ballet Russes, the still living spirit of Diaghilev, Stravinsky, Goncharova, Nijinski and the rest.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024)

Gallery view of Crafting the Ballet Russes showing a video presentation

of a modern-day performance of Afternoon of a Faun

"A new, marvelous, and totally unknown world was revealed," wrote a Parisian theater critic, after an early Ballet Russes performance.

At the Morgan Library's Crafting the Ballet Russes, this "new, marvelous, and totally unknown world" is still being revealed.

***

Text: Copyright of Ed Voves, all rights reserved Original photography, copyright of Anne Lloyd

Introductory photo:

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024) Detail of Natalii︠a︡

Goncharova ‘s curtain design for Les

Noces (The Wedding), 1915. Opaque watercolor over graphite on board: 27 x

35 x 1 1/2 in. framed. Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024) Gallery view of Crafting

the Ballet Russes exhibition at the Morgan Library and Museum.

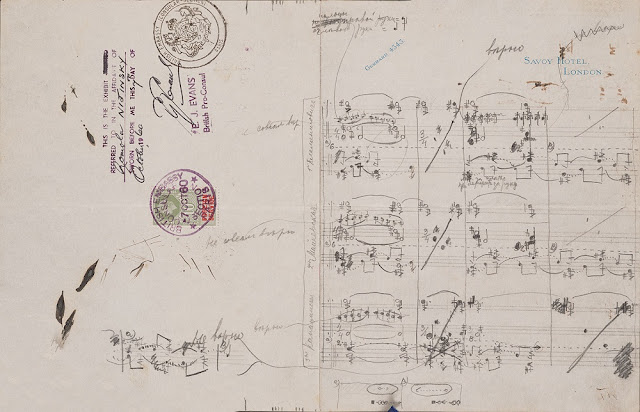

Claude Debussy (1862-1918) Prelude a l’apres-midi d’ un faune (Prelude to the Afternoon of the

Faun), 1894. Autograph manuscript. Robert Owen Lehman Collection on deposit

at the Morgan Library and Museum.

Vaslav Nijinsky (1890-1950) Choreographic notes, Afternoon of a Faun [Nijinsky’s opening

pose] [ca. 1913-1915.Graphite on paper 5 9/16 x 8 11/16 in. Library of

Congress, Bronislava Nijinska Collection

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024) Robinson McClellan lecturing on

the Ballet Russes at the Morgan Library & Museum

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024) Gallery view of Crafting

the Ballet Russes, showing photos of Vaslav Nijinsky in Afternoon of a Faun. Photo by Adolf de

Meyer, 1912.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024) Pablo Picasso’s Portrait

of Igor Stravinsky, 31 December 1920. Pencil on paper 23 x 19 x 1 7/8 in.

Famed, Private Collection

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024)

Igor

Stravinsky’s “Adagio / Supplication of

the Firebird” from Firebird (L’Oiseau de Feu). Autograph manuscript, piano,

extensive revisions, pp. 12–13, [1910], inscribed 1918 [1910] (inscribed 1918)

12 × 9 1/8 in. The Morgan Library & Museum Robert Owen Lehman Collection

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024) Igor Stravinsky ‘s The

Rite of Spring (Le Sacre du Printemps)

Sketches, 1911–1913; Facsimile Reproductions from the Autographs, pp. 96–97

[London]: Boosey & Hawkes, 1969.

Tamara Karsavina and Michel Fokine in Firebird, 1910. 14 7/8 x 12 1/2 x 1 1/2

in. framed Library of Congress, Bronislava Nijinska Collection

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024) Detail of photo of Vaslav Nijinsky and Bronislava

Nijinska in Afternoon of a Faun,

1912. Photo by Adolf de Meyer.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024) Exhibition display of postcard showing Vaslav Nijinsky as

a young dancer, ca. 1908 Russia, 1908? Autographed note from Vaslav

Nijinsky, reading “Let us dance, let us pray, let us make love”. Both from The

Morgan Library & Museum, James Fuld Collection.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024 Auguste Rodin’s Vaslav

Nijinsky in The Afternoon of a Faun

(“L’Après-midi d’un Faune”), modeled 1912, cast 1959. Bronze, marble: base

9 3/4 in. height (with base) The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, gift in

honor of B. Gerald Cantor.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024) Bronislava Nijinska in 1921 after leaving Kyiv 1921. 16

1/2 x 13 5/8 x 1 1/2 in. framed Library of Congress, Bronislava Nijinska

Collection

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024) Self-portrait of Natalii︠a︡

Goncharova , ca. 1907. Oil on canvas, mounted on board:24 3/4 x 20 3/4 x 1 5/8

in. framed Mead Art Museum, Amherst College, gift of Thomas P. Whitney

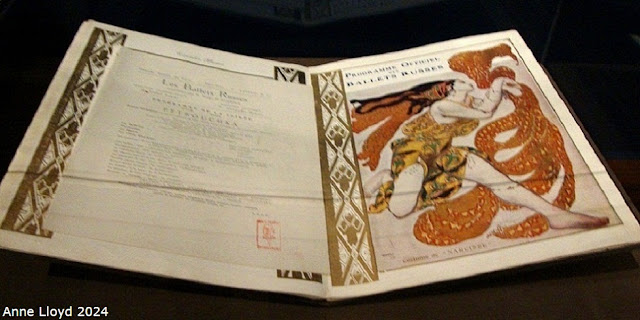

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024) Souvenir program for the 1911 Ballet

Russes season at the Theatre du Chatelet, Paris. Left page shows insert for the Petrouchka premiere; right page shows

Leon Bakst design for the ballet Narcisse.

Comoedia illustre, 1911., Paris. Morgan Library & Museum, James Fuld

Collection.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024) Detail of Natalii︠a︡

Goncharova‘s curtain design for Les

Noces (The Wedding), 1915. Opaque watercolor over graphite on board: 27 x

35 x 1 1/2 in. framed . Philadelphia Museum of Art,.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024) Mikhail Larionov’s sketch of

Sergei Diaghilev, Igor Stravinsky, and Sergey Prokofiev, ca. 1918. Graphite on

paper: 25 1/8 x 1918 x 2 in. framed. Harvard Theater collection.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024) Detail of the set design by Leon Bakst for the

bedroom scene in Schéhérazade,

1910. Gouache on paper: 24.8 x 29.1 in. (63 x 74 cm.) Boris Stavroski

collection.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024) costume design for Firebird (L’Oiseau de Feu) by Leon Bakst, 1910. Pencil, water color, and gouache,

heightened with gold on paper: 25 x 19 ½ inches famed. Private collection.

Dover Street Studios. Vaslav Nijinsky as Petrouchka, 1911. Photograph: 18 x 14

3/8 x 1 1/2 in. framed. Library of Congress, Ida Rubinstein Collection

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024) Gallery view of Crafting

the Ballet Russes exhibition at the Morgan Library and Museum, showing a video

presentation of a modern-day revival performance of Afternoon of a Faun (L’apres-midi d’ un Faune).

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment