The Art of Winold Reiss, an Immigrant Modernist

New York Historical Society, New York City

July 1, 2022 - October 9, 2022

Reviewed by Ed Voves

Original photos by Anne Lloyd

For New Americans, 1913 was a big year. Immigration records show that 1,197,892 men, women and children came to America in 1913 to live, to work and to enjoy the freedoms of the United States.

One of these immigrants was an artist and designer named Winold Reiss.

The New York Historical Society is currently presenting a major retrospective of Winold Reiss' creative oeuvre. This fascinating - and much needed -exhibition is complemented by an outstanding book, The Art of Winold Reiss, an Immigrant Modernist, published by Giles. Together, exhibition and catalog, revive the life of this amazing artist and his world.

Despite the passage of a century, Winold Reiss (1886-1953) continues to astonish us with the incredible range of artistic media in which he excelled, matched by his prodigious output.

There was an even more notable trait of Reiss than merely being a driven, modern-day "renaissance man." This was the extremely perceptive insight into American society which Reiss demonstrated very soon after he arrived in 1913.

This awareness was much more than a case of having a "fresh pair of eyes." Reiss was willing, indeed, eager to examine the cultural diversity of the United States. This vision of a new America was the foundation of his art, which in turn, he shared with students at his New York City school. Among his pupils was Aaron Douglas, celebrated today for visionary paintings such as Let My People Go and his role in the Harlem Renaissance and Civil Rights movement.

Fritz Wilhelm Winold Reiss was German, as his name clearly shows. He was born in 1886 in Karlsrue. By the time he arrived in America, the number of German immigrants had significantly diminished. For much of the nineteenth century, however, Germans had emigrated to the U.S, in vast waves, approximately eight million between 1800 to 1900.

Prior to World War I, Germans were highly regarded in the U.S. Reiss was welcome in 1913, unlike newcomers from other ethnic groups. These were suspect largely because of their religion, Roman Catholic among Italians and Poles, Jewish in the case of many of the Russian-born. Reiss, however, brought a personal attribute which the U.S. Immigration officers might have found suspect had it been included on the question sheet which needed to be completed before entry was permitted.

Winold Reiss was a Modernist artist.

Stepping ashore at Ellis Island, Reiss brought fresh cultural ideas and artistic techniques arising from the many "secession" movements in the Europe of his youth. From the Munich Secession and Berlin Secession, established in the 1890's, to the Blue Rider group, founded in 1911, German-speaking artists were especially notable for their rebellious attitudes and experimental forms of art. Reiss embraced this creative outlook but instead of joining one or another of these "secessions," he headed across the Atlantic Ocean to the United States.

Among the early works which Reiss brought with him was Perrot (1909). This oil painting is a brilliant exercise in color handling, the subtle modulation of tones of grey, mauve, olive green and creamy white marking the transition from shadow to highlight with brilliant effect.

Perrot's facial effects are key to this work - and to the personality of Reiss. The clown gives us a conspiratorial wink with one eye and a fixed, penetrating stare with the other. Perrot nonchalantly plays his tune, knowing that big changes are coming. Be prepared, a new world is coming, Perrot is saying. That is precisely what Reiss did, when he ventured to America.

Reiss brought an early version of what German art theorists would later call the "new objectivity" when he arrived in the U.S. in October 1913. Modernism had appeared a few months earlier, in February of that year, with the opening of the infamous Armory Show in New York City. Many Americans were appalled, while others cheered the art of "wild beasts" like Matisse and Duchamp.

Reiss quickly found work in America, creating book covers, magazine illustrations and providing interior design for a chain of New York City pastry shops with the delightful name of Busy Lady Bakery.

The Winold Reiss exhibition at the New York Historical Society (NYHS) is arranged in four thematic galleries. The catalog book, edited by Marilyn Satin Kushner, a curator at the NYHS, likewise includes four insightful essays. One of these, "Winold Reiss's American Studies", was written by Jeffrey C. Stewart, Pulitizer Prize winner in 2018 for his biography of Alain Locke, "father" of the Harlem Renaissance.

These catalog essays provide enlightening commentary on the seemingly unlimited scope of Reiss' art - folk art-inspired furniture, jazz-age restaurant designs, the striking mural, City of the Future, which Reiss painted in 1936, and his stunning portrait sketches, still exuding life and spirit to a startling degree.

The high quality and clarity of the illustrations in The Art of Winold Reiss, an Immigrant Modernist, combined with the compelling text, make this Giles publication an exceptional book indeed.

The design commissions which Reiss executed during the 1920's through 1940's helped establish the modern urban identity of New York City. A map in the book pinpoints 46 commercial spaces in New York City designed by Reiss, almost all in Manhattan. As might be expected, Reiss' impact on the "Big Apple" is the focus of the New York Historical Society exhibit.

It should also be noted that Reiss left his signatiure on the layout and ambiance of restaurants, hotels and civic structures across the U.S., all the way to Los Angeles. Indeed, his greatest artistic achievement was a monumental series of mosaics for the Cincinnati Union (Train) Terminal in 1933.

Later in this review, I will offer some comments on Reiss' commercial designs. But it should be noted that the real "stand-out" works of art in both exhibition and catalog are the portrait drawings in pastel and conté crayon which Reiss created celebrating the Harlem Renaissance.

Noteworthy, too, from the perspective of the Harlem Renaissance, is that this gallery of the Winold Reiss exhibition is a worthy successor to the Augusta Savage, Renaissance Woman exhibit at the NYHS, back in 2019.

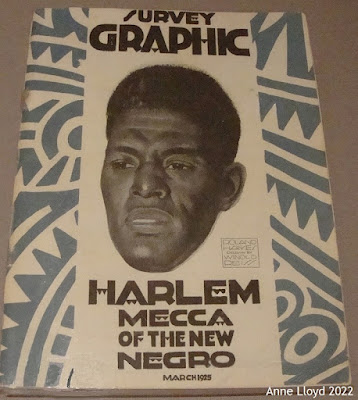

In 1924, Reiss was commissioned to provide the cover design and eighteen illustrations for a special issue of a social sciences periodical, Survey Graphic, entitled "Harlem: Mecca of the New Negro." Thirteen of Reiss' pictures in Survey Graphic were portraits of African-American notables, many of these currently gracing the deep-red gallery walls at the New York Historical Society.

As well-as Alain Locke and W.E.B. Dubois, these Harlem"notables" included four portraits of African American women.These were unnamed, but very real, individuals. They were identified by their professions, as a testimony of the ability of African Americans to excel in whatever capacity they set their minds and abilities to master. In the rather patronizing terminology of the time, these self-assured women were identified as "types."

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) The School Teachers, Type Study (detail) by Winold Reiss, 1924-25

Following the publication of "Harlem: Mecca of the New Negro", a much bigger selection of African American-themed work by Reiss was displayed at a major Harlem venue. This solo show was staged at the 135th Street Harlem Branch, New York Public Library. Curiously, it once again emphasized "types", being billed as "Exhibition of Recent Portraits of Representative Negroes."A laudatory review of Reiss's portraits by Alain Locke reveals just how important the issue of "type" was for the Harlem writers and activists during the 1920's, as they sought to counter sweeping dismissal of the achievements of African Americans as a group.

Reiss, Locke stated "is a folk-lorist of the brush and palette, seeking always the folk character back of the individual, the psychology behind the physignomy."

Regarded in this light, the brilliant sketch of Charles Spurgeon Johnson was as much a portrait of a"New Negro" man of letters as of a specific person. Today, with our emphasis on individualism, it is the indelible "finger print" of Johnson's life which matters.

And rightly so, because Johnson was a brilliant researcher for the National Urban League and editor of the prestigious publication, Opportunity, before going on to be the first African American president of Fisk University. It comes as no surprise, after closely studying Reiss' portrait of Johnson, to learn that he was a savvy social operator. Johnson funded the operating expenses of Opportunity with financial contributions from a carefully-courted group of donors, including one of the bosses of Harlem's "numbers" racket.

To focus on the issue of individual vs. "type" is important for the insight it provides about Reiss, as well as the Harlem Renaissance. Reiss had been fascinated with Native Americans since boyhood. This interest surely was a deciding factor leading him to come to America. Reiss frequently visited with Native American tribes, especially the Blackfeet of Montana.

In 1920, Reiss exhibited a series of Native American portraits, as well as Mexican ethnic "types." Examples are on view in the same gallery with his Harlem notables at the NYHS. Portraits of White Americans of different social groups appear, as well, Jazz Age flappers and grizzled working men. They make for fascinating comparison.

Reiss is likely to have believed in human "typology" since it was such a widely held concept. But at heart, Reiss was clearly an individualist in his art (and in own life). He could not repress the unique nature of each person he drew, rather than concentrating on their "representative" attributes.

We can see this "new objectivity" which Reiss applied to individuals by contrasting two portraits of rising stars of American culture. Reiss sketched Langston Hughes in 1925, Isamu Noguchi a year later. Both portraits have evocative background motifs in a similar modernist style, which makes them appear to be companion pieces.

The Hughes and Noguchi portraits are displayed together in the NYHS exhibit. It is an effective curatorial pairing but ultimately this placement only underscores the status of both men as independent masters of their own craft and their own separate destines. The background motifs are of passing interest compared to the superb handling of Hughes' fixed gaze and the sparkle of awareness in Noguchi's eyes.

Reiss imbued his portrait sketches with such a heightened degree of naturalness that his subjects seem to have been drawn yesterday rather than a century ago. Yet, they also possess aesthetic properties in common with the religious icons of medieval Christendom.

In 1927, Reiss visited St. Helena's Island on the coast of South Carolina, famous for its Gullah culture which preserves many aspect of African life. There, Reiss did a further series of portrait sketches of African Americans, this time "just plain folks" rather than celebrities like Paul Robeson or Jean Toomer.

One of these portraits imparts the nurturing quality of a Madonna by Raphael to a father figure. It is my favorite piece in the exhibit and, without exaggeration, a truly "iconic" work of art.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022)

Fred Fripp, Graduate of Penn School, with Carol and Evelyn, is such a profoundly moving portrait that I could have gazed, indeed meditated, upon it for hours, as Van Gogh did when he first beheld Rembrandt's The Jewish Bride.

Two features of Fred Frip stand out in salient fashion. The first is the powerful life force which Reiss captured in the eyes of the children. Carol and Evelyn, which merits comparison with the peering look of the Harlem teachers shown above.

And then, even more astonishing, is the evocation of the human life cycle in the way Reiss depicts the hands of these good people, the gnarled and work-worn hands of the father, the tender and trusting little fingers of his daughters, grasping his wrists.

The "human touch" so evident in this and other of Reiss' portrait drawings appears everywhere in his oeuvre, including his designs for the decor of commercial institutions. Reiss valued human happiness and he knew that this basic, need was even more important following the catastrophic "Great" War and the staggering pandemic of 1918-19.

In a revealing remark, Reiss stated that the “interiors of restaurants and hotels had to be changed to meet the modern demand. People do not want to eat in places anymore where the color of brown gravy dominates the walls and atmosphere. They want to drink their cocktails in a gay, warm surrounding where they can forget their daily worries.”

On first reading, this appears to be a fairly prosaic quote. Yet, there is much more here than an off-hand comment.

The expression "brown gravy" had been a dismissive rebuke to painters in the nineteenth century who opted for painting in the style of Rembrandt rather than follow the example of the Impressionists. Throughout his long career, Reiss rejected the "brown gravy" school of art for a bold, freewheeling realm of color.

Reiss also skillfully utilized new industrial materials, formica, aluminum, Monel Metal, in the furnishings and implements he designed. Every detail was aimed to create an atmosphere of progress and modern convenience where people could live in ease and harmony, able to be themselves.

"Freedom of choice" is a mantra of modern-day advertising. We see that exemplified in Reiss' 1939 design for a tabletop for Lindy's Restaurant. Deceptively simple, the selection of "liquid cheer", wine class, cocktail, brandy snifter and coffee cup, is set in a diamond pattern which gives the tomato red surface a welcoming, stylish appeal.

By contrast, Reiss looked back to German folk tradition in a free-standing metal sculpture for the Medieval Grill Room of the Alamac Hotel. Reiss worked with his brother, Hans, a sculptor who followed him to America. This remarkable piece was constructed of five different metals, wrought iron, copper, brass, steel and aluminum, and was fabricated by two master craftsmen, Julius Ormos and Charles Bardosy.

This magnificent panel exerts an amazing presence in the NYHS gallery, as it no doubt did in the Alamac's Medieval Grill Room. What struck me, on viewing it, was the way that the facial expressions of the dancers seem to change, depending on the light. In like fashion, the shifting movement of the shadows fills the room with a sense of lively energy. Is this a pair of metal cut-outs or two real dancers in fancy dress, "cutting the rug" in a Jazz Age Ballroom?

Yet, the artistic vision of Winold Reiss lives on, so evident in this dazzling exhibition. And, if we were to visit Glacier National Park, Montana, we might be able to commune with his spirit, as well.

When Winold Reiss died in 1953, his ashes were given to his friends of the Blackfeet Nation, who scattered them to the winds.

Text: Copyright of Ed Voves, all rights reserved.

Original photos by Anne Lloyd, all rights reserved.

Introductory Image: Book Cover of The Art of Winold Reiss, Immigrant Modernist, courtesy of Giles Publishing.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) Winold Reiss (1886–1953) Self-Portrait, version 2, 1914. Pastel on paper: 14 7/8 x 10 7/8 in. (37.8 x 27.6. cm) Private Collection

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) Composition VII ( Factories) by Winold Reiss, ca. 1917-22. Tempera on illustration board: 40 x 30 in. (101.6 x 76.2 cm) Collection of Charles K. Williams II, courtesy of Hirschi & Adler Galleries, N.Y.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) Perrot by Winold Reiss, 1909. Oil on canvas: 44 7/8 x 33 3/4 in. (114 x 85.7 cm) The Reiss Partnership

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) Gallery view of The Art of Winold Reiss exhibition at the New York Historical Society, showing Peacock Gate, 1929, Private Collection

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) City of the Future mural by Winold Reiss, for Longchamps Restaurant (1450 Broadway, at West Forty-First Street), 1936. Oil on canvas with gold paint: 56 1/2 x 192 in. (143.5 x 462.2 cm) Collection of the Kiki Kogelnik Foundation, New York

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) Elise Johnson McDougald by Winold Reiss, 1924 or 1925. Pastel on Whatman board: 30 1/16 x 21 9/16 in. (76.4 x 54.8 cm) National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of Lawrence a. Fleischman and Howard Garfinkle with a matching grant from the National Endowment for the Arts

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) Gallery view of The Art of Winold Reiss exhibition at the New York Historical Society, showing Harlem Portraits by Winold Reiss.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) Cover of Survey Graphic special issue, "Harlem: Mecca of the New Negro", March 1, 1925, by Winold Reiss. Collection of the Thomas J. Watson Library, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) The School Teachers, Type Study (detail) by Winold Reiss, 1924 or 1925. Pastel on Whatman board: 31 1/2 x 23 1/4 in. (80 x 59 cm) Fisk University Museum of Art, Nashville, Tennessee

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) Charles Spurgeon Johnson by Winold Reiss, ca. 1925. Pastel on illustration board: 30 1/16 x 21 9/16 in. (76.3 x 54.7 cm) National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of Lawrence Fleischman & Howard Garfinkle with a matching grant from the National Endowment for the Arts

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) Turtle by Winold Reiss, 1920. Conté crayon on paper: 19 1/4 x 14 1/2 in. (48.9 x 36.8 cm) The Brinton Museum, Big Horn, WY

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) Langston Hughes (detail) by Winold Reiss, ca. 1925 Pastel on Whatman board. 30 1/16 x 21 5/8 in. (76.4 x 54.9 cm) National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of W. Tjark Reiss, in memory of his father, Winold Reiss

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) Isamu Noguchi (detail) by Winold Reiss, ca. 1926 Pastel on Whatman board. 28 7/8 x 21 34 in. (73.3 x 55.3 cm) National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of Lawrence Fleischman and Howard Garfinkle with a matching grant from the National Endowment for the Arts

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) Fred Fripp, Graduate of Penn School, with Carol and Evelyn, by Winold Reiss, 1927. Mixed media on Whatman board. 30 x 22 1/2 in. (76.2 x 57.2 cm) Fisk University Museum of Art, Nashville, Tennessee

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) Study for Interior, Longchamps Restaurant at Manhattan House (corner of Third Avenue at 65th St.), 1950 or 1951. Graphite & tempera on illustration board: 21 x 31 in. (53.4 x 78.8 cm) Private Collection

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) Tabletop for Lindy's Restaurant, by Winold Reiss, 1939. Formica with aluminum inlay and metal edge banding: 26 x 26 x 1 1/4 in. (66 x 66 x 3.1 cm) Private Collection

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) Panel from Medieval Grill Room, Alamac Hotel, designed by Winold Reiss and Hans Reiss; Jules Ormos and Charles Bardosy, metalwork fabricators, 1923. Wrought iron, copper, brass, steel and aluminum: 55 1/4 x 52 1/4 x 2 in. (140.3 x 132.7 x 5.1 cm) Private Collection

No comments:

Post a Comment