Eye of the Beholder:

Johannes Vermeer, Antoni van Leeuwenhoek and the Reinvention of Seeing

By Laura J. Snyder

W.W. Norton/$27.95/432 pages

Johannes Vermeer, Woman Holding a Balance, c. 1664

Joris Hoefnagel, Animalia Rationalia et Insecta (Ignis), c. 1575/1580

Portrait of Antoni van Leeuwenhoek, Mezzotint by J. Verkolje

W.W. Norton/$27.95/432 pages

Reviewed by Ed Voves

As I finished reading Eye of the Beholder, Laura J. Snyder's compelling study of art and science during the Dutch Golden Age, I recalled the "Two Cultures" debate from the mid-twentieth century.

In 1959, the British scientist and novelist, C.P. Snow delivered an influential speech at Cambridge University. Snow's theme dealt with the widening chasm between the realm of art and literature on one side and the domain of science on the other. Snow's multi-faceted career proved that the humanities and the sciences need not travel on separate paths. Yet, that was the direction, Snow contended, that intellectual development was taking.

Pointing to the lack of dialog between the two disciplines, Snow delivered a heavy verdict upon the literary and artistic elite:

So the great edifice of modern physics goes up, and the majority of the cleverest people in the western world have about as much insight into it as their Neolithic ancestors would have had.

Their seventeenth century ancestors might have had a better grasp on reality. For this was the age of public figures steeped in the knowledge of the arts and sciences, men like Francis Bacon, Constantijn Huygens and the worthy gentlemen who founded the Royal Society in England. To be an "amateur" scientist or savant (in the parlance of the day) was no disgrace. Indeed, the Dutch had a delightful badge of honor for such high-minded dabblers: "Heeren curiuse Liefhebbers."

More to the point, the 1600's witnessed the world-changing contributions of two men from the city of Delft in Holland. Their achievements reveal the balance and interdependence of art and science during the seventeenth century. There was no "Two Cultures" divide in the Netherlands during the Golden Age.

Johannes Vermeer, Woman Holding a Balance, c. 1664

Antoni van Leeuwenhoek (1632- 1723), the discoverer of the unseen, unsuspected realm of micro-organisms, and the enigmatic painter, Johannes Vermeer (1632- 1675), are the two protagonists of Eye of the Beholder.

Leeuwenhoek and Vermeer lived very close to each, diagonally across Delft's market square. Leewenhoek certainly knew of Vermeer. In 1676, he was appointed by "Their worships the Sherriffs of the Town of Delft" to be the executor for Vermeer's widow who was entangled in the financial ruin left by Vermeer at his death, the year before.

Unfortunately, not one shred of documentary evidence survives, attesting to any form of contact between Leeuwenhoek and Vermeer. But it is highly unlikely they never met and Laura Snyder cogently explorers the possible, indeed likely, points of interaction.

What the two men from Delft shared in common was a fascination with the study of optics. This discipline was at the cutting edge of the Scientific Revolution. The telescope, first patented in Holland in 1608, had become a factor, relatively late but increasingly important, in the momentous debate over the heliocentric model of the solar system proposed by Copernicus.

It was left to the Dutch with their astonishing skill at making lenses and their practical, result-based work ethic to focus the optical tools of the Scientific Revolution on matters closer to home.

Lenses, in the form of eye glasses or magnifying glasses had been in use for centuries. The 1500's had witnessed a growing interest in accurately depicting the natural world. With the aid of a magnifying glass, the Flemish painter Joris Hoefnagel (1542 - 1600) painted amazingly detailed pictures of insects like these dragonflies.

Joris Hoefnagel, Animalia Rationalia et Insecta (Ignis), c. 1575/1580

Painters of the Baroque period likewise dedicated great effort to capture the effect of light and shadow. Caravaggio's The Calling of St. Matthew is particularly notable in this respect.

In both cases, artists and scientists before 1600 had not advanced much beyond what could be seen with the naked eye. There were unseen "New Worlds" waiting to be discovered. Leeuwenhoek and Vermeer would be key players in the exploration.

Portrait of Antoni van Leeuwenhoek, Mezzotint by J. Verkolje

Leeuwenhoek came from a solid, respectable, middle class background. Leeuwenhoek's father was a basket maker, an important trade for an exporting country like the Netherlands. Leeuwenhoek's stepfather, Jacob Molijn, interestingly, was a painter who specialized in heraldic coats of arms. The honorific "van" in Leeuwenhoek's name was not inherited, but was adopted by him after his election to the Royal Society in England in 1680.

Vermeer's family history was more notorious than noteworthy. His maternal grandfather and great-grandfather had been implicated in a counter-fitting scheme. Vermeer's father, by turns a cloth maker, inn keeper and art dealer, concocted the Vermeer surname to lend the family some respectability.

In 1653, the young Vermeer registered with the Guild of St. Luke as a painter. There is some speculation that Vermeer was self-taught though Snyder believes he was trained according to the normal apprenticeship method. Significantly, he kept on with the family business as an art agent.

The key factor in both Leeuwenhoek's and Vermeer's upbringing was their training in a profession. They needed to earn their living. Leeuwenhoek started out as a draper's apprentice and became interested in magnifying lenses to help him apprise the quality of cloth. It was but a short step for Vermeer from selling paintings to creating them.

Leeuwenhoek summed up the work ethic, initially entailed in selling cloth, but later in making lenses and conducting microscope studies:

"A man has always to be busy with his thoughts if anything is to be accomplished."

Neither Leeuwenhoek nor Vermeer had the time to bother with the "higher theories" that Rene Descartes and other university-trained scholars proposed. The litmus test of practical experience, not preconceived ideas, was the focus of their lives.

Optical devices from the 1600's, examples of camera obscura at top

The optical studies of Leeuwenhoek with his hand-held microscopes and Vermeer with the viewing device known as a camera obscura followed the same course: look, focus, observe, record ... look, focus, observe, record.

This of course is the scientific method in action, but Leeuwenhoek and Vermeer were doing more than following the steps of the experimental approach. Both were involved in a great perceptual leap-forward. Snyder writes brilliantly:

The work of Van Leeuwenhoek and Vermeer exemplified a particular notion of seeing, one that emerged only in this period with the birth of optical instruments and the new theories of vision. This notion accepted that seeing was a complex matter - involving much more than just rays coming either to or from the viewer's eye. Beliefs, expectations, desires and prior knowledge all play a role in how we see the world. As Galileo had said, one must use "the eyes of the mind as well as the eyes in the head" in order truly to see..."

The eyes of Leeuwenhoek's mind were certainly open. But he enhanced his vision with amazingly powerful microscopes which he made himself. These single-lens instruments had a magnifying power of 200x, compared to the more elaborate compound microscopes of the time which possessed magnification of only 20x to 30x.

In an incredibly short span of time, the former draper's apprentice from Delft used his microscopes to discover the unseen world of what he called animalcules or "little animals." Leeuwenhoek's discovery of protozoa (1674), bacteria (1676), blood corpuscles (1674) and blood capillaries (1683) totally transformed the study of biology.

Blood corpuscles depicted by Antoni van Leeuwenhoek

Leeuwenhoek also spent considerable effort helping others to see with the "eyes of the mind." It was not always an easy process. Even Christiaan Huygens, the brilliant son of Constantijn Huygens, could not identify blood corpuscles when Leeuwenhoek sent him a sample in "small Glass-pipes." And Christiaan Huygens was one of the greatest scientists of the age!

Leeuwenhoek's discoveries were so revolutionary that it took nearly two centuries before all of the implications of this new, unsuspected realm of knowledge could be understood.

Leeuwenhoek maintained a charming, if naive, fondness for the "little animals" he studied swimming about before his microscope lenses. He never grasped that some of them were harmful to humans, indeed deadly pathogens.

It was not until 1848, that the Hungarian scientist, Ignaz Semmelweis, deduced that puerperal or childbirth fever was caused by “cadaveric particles.” These were carried on the unclean hands of physicians who went from performing autopsies to delivering babies. It took another fifteen years before these “cadaveric particles” were identified as streptococci bacteria, easily removed by washing one's hands.

Ironically, it was at the same point that the scientific world grasped the implications of Leeuwenhoek's discovery of micro-organisms that Vermeer’s paintings were rediscovered. As I noted in a recent post, the French journalist, Theophile Thoré, chanced upon a painting by Vermeer during a visit to Holland in 1842. Vermeer had been totally forgotten by this point. Most of the few Vermeer paintings on display in museums were attributed to Pieter de Hooch or Gabriel Metsu.

Johannes Vermeer, Woman with a Water Pitcher, c. 1662

With an impressive command of seventeenth century science and art, Snyder underscores the revolutionary impact of Vermeer's study of optics. Vermeer, she argues, did not utilize the camera obscura as a mere tracing apparatus. Snyder cogently states that:

Vermeer used the camera obscura to develop his sense of sight, to notice natural optical effects lesser painters had missed: the color of shadows, the way an object changes color depending on the lighting, how light glances off the nails of a chair. He realized, too, that visual perception fills in missing details when the viewer has certain expectations.

Johannes Vermeer, A Lady Writing, c. 1665

In short, Vermeer trained his eyes - and the eyes of his mind - to see. Galileo, and Leeuwenhoek did so as well and in due course Isaac Newton, and (eventually) Christiaan Huygens would follow. What these remarkable men of the seventeenth century did was to unite the methodologies of the arts and sciences to create the matrix of the modern world.

In the moving summation of her splendid book, Laura Snyder maintains that the perceptual revolution initiated by Leeuwenhoek and Vermeer altered the very way that human beings view their place in the world. The achievements of these optical pioneers created a "before this moment and after it."

It took centuries to grasp that fact and in many ways we are still grappling with the legacy of these visionary Dutchmen. But after the age of Leeuwenhoek and Vermeer, there was no way for humanity to remain focused on received theories of information and misinformation from the hallowed past.

Following the lead of Leeuwenhoek and Vermeer, we can only look forward - and upward, inward and all around us.

***

Text: Copyright of Ed Voves, all rights reserved

Images courtesy of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, the Wellcome Library, London, and W.W. Norton.

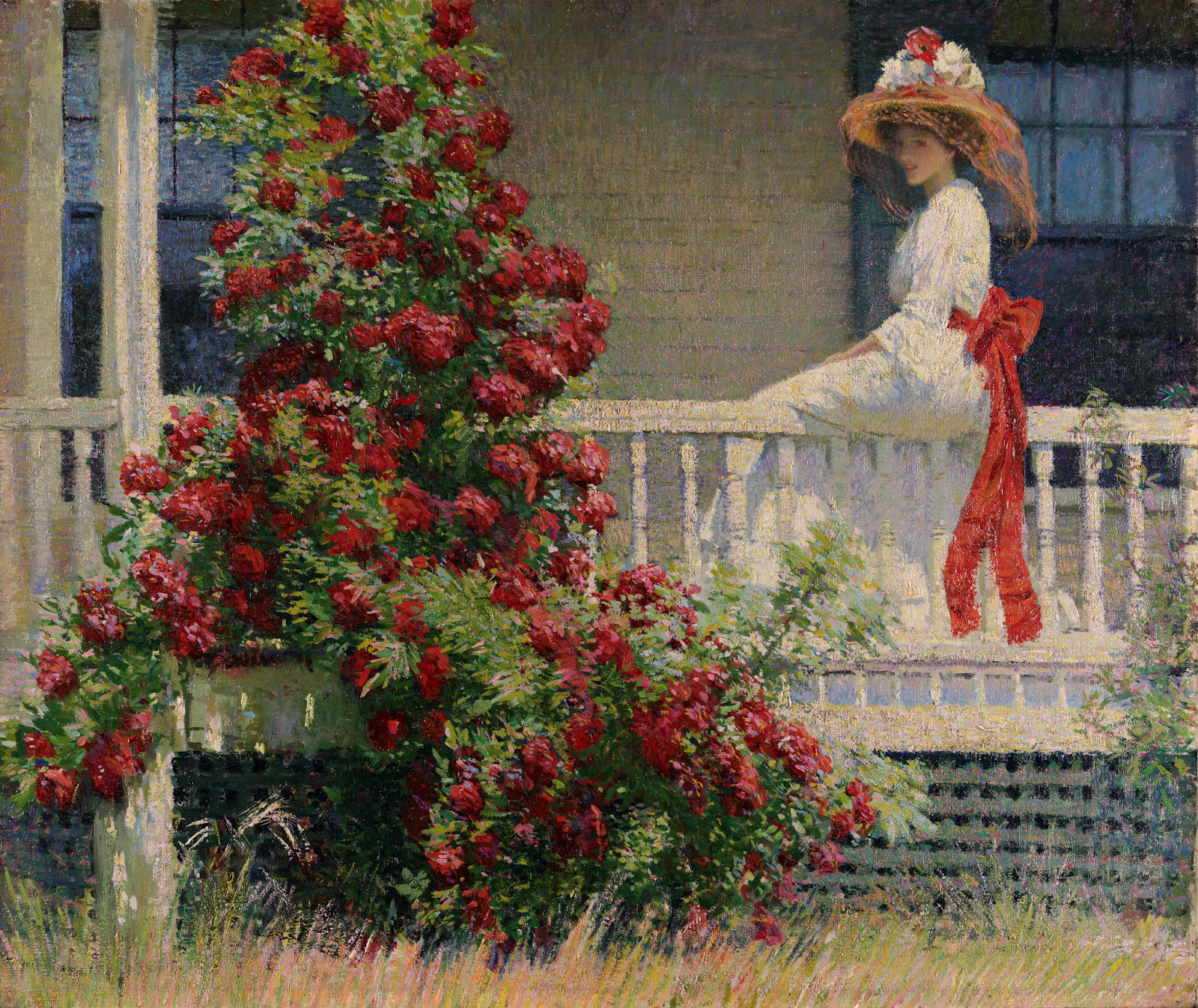

Introductory Image Cover Image Courtesy of W.W. Norton

Johannes Vermeer (Dutch, 1632 - 1675), Woman Holding a Balance, c. 1664, Oil on canvas painted surface, 39.7 x 35.5 cm (15 5/8 x 14 in.) stretcher size: 42.5 x 38 cm (16 3/4 x 14 15/16 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C Widener Collection 1942.9.97

Joris Hoefnagel (Flemish, 1542 - 1600), Animalia Rationalia et Insecta (Ignis): Plate LIV, c. 1575/1580, Watercolor and gouache, with oval border in gold, on vellum, page size (approximate): 14.3 x 18.4 cm (5 5/8 x 7 1/4 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C Gift of Mrs. Lessing J. Rosenwald 1987.20.5.55

Portrait of A. van Leeuwenhoek, three quarter length, seated. Mezzotint (by J. Verkolje) 1686 Wellcome Library, London, V0003466 (Library reference no.: Iconographic Collection 1719.1)

Jacques-Raymond Lucotte (French, active 18th century), Optics: camera obscura (top) and a Leeuwenhoek style microscope (below). Engraving by Robert Bénard [after Lucotte]. Published: Paris, Size: image and border 30.7 x 19.8 cm. Wellcome Library, London V0025361 (Library reference no.: ICV No 25808)

Leeuwenhoek simple microscope (copy - unknown maker), Leyden, Netherlands, 1901-1930 . Science Museum, London, Wellcome Images L0057739 (Library reference no.: Science Museum A500644)

Blood corpuscles depicted by Antoni van Leeuwenhoek, From: Arcana Natura Detecta by: Antoni van Leeuwenhoek, 1719. Plate page 220, Figure 1-7. Wellcome Images, Photo number: M0010779 (Library reference no.: External Reference W.R.L. 42550 and Slide number 2261)

Johannes Vermeer (Dutch, 1632 - 1675), Woman with a Water Pitcher, c. 1662, Oil on canvas,18 x 16 in. (45.7 x 40.6 cm), The Metropolitan Museum of Art Marquand Collection, Gift of Henry G. Marquand, 1889 Accession Number: 89.15.21 © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Johannes Vermeer (Dutch, 1632 - 1675), A Lady Writing, c. 1665, Oil on canvas, overall: 45 x 39.9 cm (17 11/16 x 15 11/16 in.) framed: 68.3 x 62.2 x 7 cm (26 7/8 x 24 1/2 x 2 3/4 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C Gift of Harry Waldron Havemeyer and Horace Havemeyer, Jr., in memory of their father, Horace Havemeyer 1962.10.1