Medieval Treasures from the Glencairn Museum

Philadelphia Museum of Art

June 24, 2022 - Autumn 2023

Reviewed by Ed Voves

Original photos by Anne Lloyd

In the prologue to Henry V, William Shakespeare asked if the "cockpit" of the Globe Theatre, shaped like a "wooden o", could provide the setting for retelling the story of the Battle of Agincourt.

We can well raise similar questions about the effectiveness of museums in presenting special exhibitions. When carefully chosen works of art are displayed in a gallery space, can they call forth a "Muse of fire" to ignite our imaginations as Shakespeare did?

In the case of a small, focused exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Medieval Treasures from the Glencairn Museum, the answer is a resounding yes!

A choice selection from Glencairn's renowned collection of art from the Middle Ages is on view in the exhibit, a long-term loan while building renovations are being made at Glencairn.

From masterpieces of carved ivory, the earliest dating to around the year 500, to luminous stained glass panels from the era of the Gothic Cathedrals, the exhibition distills the very essence of the culture of Christendom.

Medieval art was overwhelmingly spiritual in orientation and intended for instructional purposes. But the core humanity of the people who populate the scenes of sacred history on the stained glass panels and church sculptures from Glencairn often transcend the boundaries of theological doctrines.

When we view the greeting of the Virgin Mary and her older cousin, Anne, in this depiction of the biblical episode known as the Visitation, we are moved to join in their embrace - and extend it to all humanity. Over and over again, the Glencain "treasures" banish all lingering prejudices regarding the medieval era as a "dark age."

In the early summer of 2021, I visited the Glencairn Museum, located in Bryn Athyn, PA, about fifteen miles north of center city Philadelphia. I won't repeat the story of how the Bryn Athyn Cathedral and the Glencairn Museum came to be built by Raymond Pitcairn (1885-1966). But it has to be emphasized, once again, that "Pitcairn brought the passion and work ethic of the castle and cathedral builders of the Middle Ages to his great venture."

Like Bishop Bernward, patron of the great German abbey church of St. Michael's at Hildesheim (built 1001-1031) and Abbot Suger, who pioneered the design of Gothic cathedrals a century later, Pitcairn believed in acquiring treasures of religious art to display in his magnificent edifice.

Although Glencairn has excellent examples of ancient Egyptian, Graeco-Roman and religious art from around the world, medieval European art is the museum's premier attraction. Pitcairn collected approximately 600 works of art, mostly from the Romanesque and early Gothic periods in France, 1100-1300, with special attention to stone carvings and stained glass window panels.

From this world-class array of medieval art, curator Jack Hinton of the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA) chose 18 magnificent works of art. But before we examine these treasures from Glencairn, two important points need to be underscored.

Medieval Treasures from the Glencairn Museum is the latest collaboration between the two museums, dating back to the 1930's. There are a number of other Glencairn works currently on view in the medieval galleries of the PMA. Indeed, some have been on long-term loan for so many years that these works appear to be permanent features of the PMA.

This is the case for one of the museum's most effective displays, the pairing of a late thirteenth century crucifixion from Glencairn with the tomb effigy of a recumbent knight from the PMA's collection.

This Corpus of Christ (as the painted wooden statue is also called) reflects the emphasis upon Jesus' humanity and suffering as preached by St. Francis of Assisi (1181/82-1226). When placed above the monument to an unknown knight of the Crusading-era, this sculptural ensemble symbolizes Europe's Age of Faith in a profoundly moving way.

It is entirely fitting that Medieval Treasures from the Glencairn Museum is on display in one of the PMA's galleries devoted to the Middle Ages, only a moment's walk from the Corpus of Christ and the sleeping knight. Stepping through the doorway of Gallery 307 to view the exhibit evokes the feeling of arriving at journey's end on a medieval pilgrimage.

The first works of art to strike the eye upon entering the exhibit is the bank of five radiant panels of stained glass from the early Gothic era. These are positioned on the wall opposite to the door, yet their appeal is impossible to resist.

I was drawn immediately to these wondrous art works, particularly to the central panel, The Flight into Egypt. Commissioned by Abbot Suger for the reconstruction of the royal chapel of France, the Abbey Church at Saint-Denis, it dates to 1140-1144. This rare, color-drenched panel is one of the earliest surviving pieces of stained glass in an American art collection.

The Flight into Egypt was also, for several years during the 1970's, a very controversial work of art. Scholarly opinion was divided on whether it was a forgery. It took a long, intensive campaign to prove its authenticity. The dogged determination of a Columbia University grad student, Michael Cothren, and the scientific analysis of Robert Brill of the Corning Museum of Glass insured that The Flight into Egypt regained its status as one of the world's greatest works of medieval art.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) The Flight into Egypt, from the Chapel of St. Denis, c. 1145

To describe The Flight into Egypt as iconic is, for once, entirely appropriate.After only a few moments of viewing The Flight into Egypt, one can begin to reach a better understanding of the medieval world view. It was a state of mind where the biblical past was very much alive. Religious pilgrimages figured prominently as deeds of faith. And if one could not make the ultimate journey to Jerusalem, then a visit to a cathedral closer to home, emblazoned with stained glass windows depicting the lives of Jesus, his mother Mary and other saintly persons, would suffice.

Likewise, people during the Middle Ages had no problem in believing tales not found in sacred scripture. In The Flight into Egypt, we see Mary picking a fig from a tree which her infant son (who looks remarkably mature) had commanded to lower its branch for her convenience. Incredible, even ridiculous, to our minds, yet such a story would have given encouragement to pilgrims enduring an arduous journey to Chartres, Santiago or even Jerusalem.

Another of the Glencairn stained glass panels strikes an even more apocryphal note. In the legend of the Seven Sleepers of Ephesus, a group of early Christians, fleeing persecution, sought refuge in a cave, which was sealed-up by Roman soldiers. Instead of dying, they fall asleep, waking-up many years later like Rip van Winkle.

One of the seven, Malchus, is arrested for trying to buy bread for breakfast with a now-vintage Roman coin. Ephesus, his home town, had converted to Christianity while he and his companions slumbered, but Malchus, as we see in the charming scene, above, is once again on the wrong side of the law.

Miraculous or far-fetched - or somewhere in between - stories drawn from the Bible and popular religious tales were best told in pictorial format. Romanesque churches featured vigorous, colorful fresco paintings, but in the cold, damp climate of Europe, north of the Alps, these quickly lost their lustre. Stained glass, far more difficult to create, lasted longer. The master glass makers of the Gothic cathedrals, developed an eye for dramatic scene composition that modern-day film makers could not surpass.

The economy of creative effort used in creating narratives of Gothic-era stained glass is readily apparent in Salome Dancing at the Feast of Herod. This was one of a series of roundels depicting the life and death of St. John the Baptist from a church in northern France. While the series progresses like movie storyboards, each roundel is brilliantly self-contained, none more so than this one of sexy Salome's dance.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) Salome Dancing at the Feast of Herod, c. 1235

Here we see the sword-wielding Salome, gyrating at the feet of Herod Antipas. Her mother, Herodias, urges the irresolute Herod to strike at John the Baptist. While the other scenes in the series, (Glencairn owns two more) are equally forceful, this brilliant episode is an absolute masterpiece.This array of stained glass panels is so brilliant that it was hard to redirect my attention to the other works of art in Medieval Treasures from the Glencairn Museum. Yet, just a few feet away was a Romanesque sculpture, carved from limestone around 1150-60, which rivals the narrative inventiveness and emotional intensity of the stained glass panels.

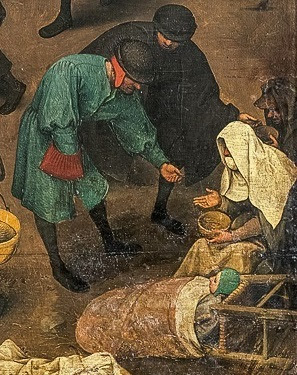

Capital with the Story of Dives and Lazarus would have perched atop a column at the Abbey of Moutiers-Saint-Jean, France. It shows Jesus' parable of the pious, impoverished Lazarus and rich, selfish Dives. Lazarus dies in misery but is redeemed, coming to rest "in the bosom of Abraham." Dives, clutched in the jaws of damnation, begs that Lazarus dip his finger into water to relieve his agony.

Romanesque sculptures like this capital were once viewed as "primitive" but are now regarded as masterful interpretations of the conflict of good and evil. If outwardly simplistic in its moral judgement, the Lazarus/Dives carving conveys a degree of psychological intensity that certainly informed the mind and guided the hand of the sculptor who made it.

The terror on the face of Dives when he realizes that he faces divine wrath for his cruel, heedless mistreatment of Lazarus is unforgettable, ranking with images from classic cinema of the 1920's or Francis Bacon's "screaming" popes.

Detail of Capital with the Story of Dives and Lazarus, c.1150-60

Skillful story-telling is indeed a prevailing theme of medeaval art. To an amazing degree, Medieval Treasures from the Glencairn Museum evokes the spirit of the Middle Ages. The "genius" is there in the details of these works and in their skillful juxtaposition in the display cases of the exhibition.

Two small artifacts - incredibly so - offer insight into the development of medieval art. The first is a small box, carved from ivory, in Spain, around the year 700. It is placed next to a sculpted "crowned" head, hardly bigger than a man's clenched fist. Together, these diminutive works of art reveal much about the course of European art during the early Middle Ages.

The carving on the ivory box narrates two episodes in the life of King Solomon, including his crafty judgement of ordering a baby sliced in two, so that rival women, each claiming to be the child's mother, coud have an equal share of the corpse. (The deed, thankfully, never was carried out.)

Though the incident was biblical in origin, the carving on the box was entirely Germanic. Spain, following the collapse of Roman rule, was dominated by Visigothic kings. Brave in battle but inept as administrators, the Visigoths succumbed to the Moorish invasion of Spain in 711.

The ineffectual rule of the Visigoths is reflected in this curious ivory box. But the "crowned" head, displayed in the same case, shows how far the artistic skill of Europe's sculptors had progressed by the time it was carved, sometime in the early 1100's. It too represents a king, perhaps King Solomon. But the identity of the maker, rather than the subject, is what counts.

The man who carved this Head of a King was almost certainly Giselbertus. His reputation as "one of the great geniuses of medieval art" is based on the astonishing carved scene of the Last Judgement which he sculpted for Autun Cathedral, 1125-1130. Skill alone, however, does not account for the renown of Giselbertus. At the base of his depiction of Christ at Autun, Giselbertus contributed an unexpected detail: his name.

Giselbertus hoc fecit. Giselbertus made this.

Looking at this small head reveals that its features are very similar to those on the figures of the Autun Last Judgement. This is the main reason that scholars believe it was carved by Giselbertus. For my part, I was struck by the mobility of expression of the face, of the fey quality of the character of the king, when viewed from different angles. He looks sly and devious on one side, impassive on the other. This might well be a portrait of King Solomon.

In signing his name on the Autun sculpture, Giselbertus brought medieval art to the point where artists ceased being anonymous. Credit would be given where it was due. Centuries would pass before this process would be complete, but thanks to Giselbertus, artistic individualism had received a huge boost.

This transition in art, from Romanesque to Gothic, with growing public recognition for artists, is the endpoint of the Medieval Treasures from Glencairn exhibit. But the modern-day part of the story has a further chapter to relate: the important role which Raymond Pitcairn played in the development of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

When the Philadelphia Museum of Art opened in 1927, its first director, Fiske Kimball, worked on a master plan to transform the museum's third floor into a chronological succession of galleries and period rooms. When complete, this would enable art lovers to follow the course of Western art from the Middle Ages to modern times.

Fiske Kimball, a brilliant scholar of architecture, was able to place in the museum galleries surviving remains from historic buildings in Europe such as the fountain from the Monastery of St Michel-de-Cuxa and the Portal of the Abbey of Saint-Laurent. This gives visitors a "you are there" passport to the Middle Ages.

However, the PMA's master plan soon hit a major obstacle. The Stock Market collapse of 1929 and the ensuing Great Depression gravely affected donations of funds and works of art to the museum. Many of the galleries remained empty. As Fiske Kimball and his staff labored to achieve their audacious goal, critics lampooned the museum as a "Grecian parking garage."

Raymond Pitcairn helped Fiske Kimball deal with the dilemma of providing works of art for the fourteen galleries designated for the study of medieval art and culture. During the Depression decade, Pitcairn loaned approximately 70 art works to the PMA, along with several donations. The loans included many of his most treasured sculptures and paintings including the fourteenth century fresco, Christ in Majesty, from a church in Spoleto, Italy.

As noted earlier, in the case of the Corpus of Christ, many of Pitcairn's loaned art works graced the medieval galleries of the PMA for very long periods of time. Even after 1945, when funds became available for Fiske Kimball to purchase a large collection of medieval art for the PMA, Pitcairn continued to generously support the museum.

As I left Gallery 307, where Medieval Treasures from the Glencairn Museum will hang until repairs at Glencairn are finished in the fall of 2023, I was in a thoughtful mood. I reflected on the vital role of enlightened artists and patrons, whose contributions make civilized life meaningful - indeed possible.

Where would we be without visionaries like Abbot Suger, without the stained glass masters who made The Flight into Egypt or gifted sculptors like Giselbertus?

Where would we be - in our own age of great wars, great plagues and great depression - without the likes of Raymond Pitcairn?

***

Text: Copyright of Ed Voves, all rights reserved Images copyright of Anne Lloyd

Introductory Image:

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) The Flight into Egypt, from the Infancy of Christ Window (detail)

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) Gallery view of Medieval Treasures from the Glencairn Museum at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) The Visitation from the Church of St. Radegonde. Artist unknown, France. Stained glass. c. 1270-1275. 30 1/2 × 23 7/8 inches (77.5 × 60.6 cm). On loan from Glencairn Museum, Bryn Athyn, PA.

Ed Voves, Photo (2021) View of Glencairn Museum, Bryn Athyn, PA

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2021) Gallery view of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, showing Corpus of Christ, late 13th century, painted wooden statue on loan from the Glencairn Museum and Recumbent Knight from a Tomb Sculpture, France, c. 1230, from the Philadelphia Museum of Art collection.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) Entrance to the Medieval Treasures from the Glencairn Museum exhibit at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) View of Stained Glass Panels from the Glencairn Museum Collection.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) The Flight into Egypt, from the Infancy of Christ Window (?), from the Abbey Church of St. Denis, France. Stained glass. c. 1145. 20 1/2 × 19 3/4 inches (52.1 × 50.2 cm). On loan from Glencairn Museum, Bryn Athyn, PA.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) The Flight into Egypt (detail)

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) Malchus is Led before the Bishop and Prefect from The Seven Sleepers of Ephesus window of the nave aisle of Rouen Cathedral. Stained glass. c. 1200-1203. 24 1/2 × 23 1/4 inches (62.6 × 59 cm).On loan from Glencairn Museum

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) Salome Dancing at the Feast of Herod, Stained glass roundel from the Church of Saint-Martin, Breuil-le-Vert, France, c.1235. diameter: 47. 5 cm. (18 11/16 inches) On loan from Glencairn Museum, Bryn Athyn, PA.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) Capital with the Story of Dives and Lazarus. Artist unknown, from the Abbey of Moutiers-Saint-Jean, France. Limestone. c. 1150-60. 25 × 11 × 14 1/2 inches (63.5 × 27.9 × 36.8 cm). On loan from Glencairn Museum, Bryn Athyn, PA.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) Capital with the Story of Dives and Lazarus (detail)

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) Gallery view of Medieval Treasures from Glencairn Museum, showing Ivory Box from Spain & Sculpted Head by Giselbertus

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) Box with Scenes from the Book of Kings. Artist Unknown, Spain. Ivory. c. 700. Approx.: 3 × 6 × 3 inches (7.6 × 15.2 × 7.6 cm). On loan from Glencairn Museum, Bryn Athyn, PA.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) Head of a King. Attributed to Giselbertus, from Autun, Burgundy. Limestone. Mid-1100's. 5 1/8 × 3 1/4 × 3 5/8 inches (13× 8.2 × 9.2 cm). On loan from Glencairn Museum, Bryn Athyn, PA.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) Corpus of Christ, late 1200's, from the Glencairn Museum collection, on view at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) Border panel, from the Moses Window (?), Artist Unknown, Abbey Church of Saint-Denis, France. Stained glass. c. 1145. 19 1/4 × 9 inches (48.9 × 22.9 cm). On loan from Glencairn Museum

.jpg)