The Artist's Garden:

American Impressionism and The Garden Movement, 1887—1920

The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA)

February 13, 2015 - May 24, 2015

The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA)

February 13, 2015 - May 24, 2015

Reviewed by Ed Voves

The Artist's Garden: American Impressionism and The Garden Movement, 1887—1920, takes a fresh look at the landscape tradition from the standpoint of our own backyard. The new exhibition at the Pennsylvania Academy of Art presents dazzling art and vintage "green thumb" gardening books from the late-Victorian era through the end of the First World War.

Cecilia Beaux, Landscape with Farm Building, Concarneau, France, 1888

The PAFA exhibit is certainly a feast for the eyes. It is an expansive exhibition with art work by virtually every American artist of the period, including Cecilia Beaux (1855- 1942) and William Merritt Chase (1849-1916).

Bessie Potter Vonnoh (1872-1955), Water Lilies Fountain, 1913

The ideals of beauty and innocence from the years before the First World War are evoked by two exquisite garden statues by Harriet Whitney Frishmuth (1880-1980) and Bessie Potter Vonnoh (1872-1955).

An additional feature of the PAFA display is a companion exhibit, Gardens on Paper. Along with rare prints, this exhibit presents an array of early color photographs, discovered in the Pennsylvania Academy’s archives. These Autochromes, the earliest method of color photography, show the garden of artist Thomas Shields Clarke at his home in Lenox, Massachusetts. I hope to do a separate post on these incredible images.

Thomas Shields Clarke, Photographic Autochrome, ca. 1910

The Artist's Garden is not just an occasion for displaying paintings of verdant fields or striking works of stained glass. There is a subtext to the exhibition, the lurking presence of daunting social problems besetting American culture at the turn of the twentieth century.

American Impressionism began when young artists from the U.S. traveled to France to study and paint with Claude Monet at his idyllic retreat, Giverny. The Americans produced works of beauty that matched some of the best work done by the great Impressionist master and his colleagues, Renoir, Sisley, Pissarro.

John Leslie Breck (1860-1899) was one of the first American painters - with the obvious exception of Mary Cassatt - to embrace Impressionism. There is no sign of humanity in his landscape, Garden in Giverny, just dense masses of flowers, seemingly untended, and an empty path. But there is such a powerful sense of being in this work that one senses the presence of the natural world in a direct, almost personal manner.

John Leslie Breck, Garden at Giverny, between 1887-91

Many of the American Impressionists followed in Breck’s footsteps, painting works of nature with little sign of human mediation. Color, itself, in the dazzling garden and flowering field, was an invitation to the Impressionist style as the artist Charles Curran noted in a 1909 article discussing the work of his colleague, Willard Metcalf.

In looking at such a gorgeous mass of flowers in nature the eye would be so filled with the richness and profusion of forms that the precise form of no one particular flower would be noticed. It would detract greatly from the charm of such a picture if each flower were sharply drawn in detail…

Impressionism then was suited to the vision of American painters who embraced it so readily. The world of art, however, had already moved on by the time that they began painting en plein air in France. The joint Impressionist exhibitions in Paris ceased after 1886. Symbolism, with its powerful explorations of the human psyche, was gaining in notoriety. The brilliant landscapes painted by the American Impressionists could thus be seen as the final flourish of an avant-garde art movement that was soon to be overshadowed by more radical artistic oeuvres.

American Impressionism and the Garden Movement can be interpreted in another light, however. They were vigorous responses to the changing circumstances of life in the United States following the Civil War. These post-war decades were dubbed the "Gilded Age" by Mark Twain. But "Iron Age" is a more accurate title.

As the U.S. economy surged past Great Britain and Germany, the environmental and social costs of breakneck industrialism could not be disregarded for long. The vast slag heaps of the coal industry and the polluted rivers threatened the image of America the Beautiful. The shocking disparity between the standard of living of the "Social Register" few and that of the impoverished “Masses” threatened the ideals of America the Just.

Nostalgia, combined with concern for the future, nurtured the Colonial Garden Movement. Beginning with displays at the Centennial Exhibition held in Philadelphia in 1876, theories about the "simplicity" of life during the eighteenth century exerted a widespread appeal. From the design of gardens and the emphasis on planting native or vintage flowers to the decoration of summer homes, a popular, romantic image of Early America took hold, countering the crass, "shoddy" reality of the late 1800's.

As the PAFA exhibit details, the Garden Movement was influenced by the cultural background of Philadelphia and the New Hope art colony in nearby Bucks County. Philadelphia was a city with a deep-rooted "club" tradition reaching back to Benjamin Franklin's Junto. In 1913, the Garden Club of America was founded in Philadelphia. The city was also the home of the Burpee Seed Company, founded in 1876. The world's largest mail order seed company, Burpee’s Seeds enabled a new generation of plant and flower enthusiasts to swell the Garden Movement.

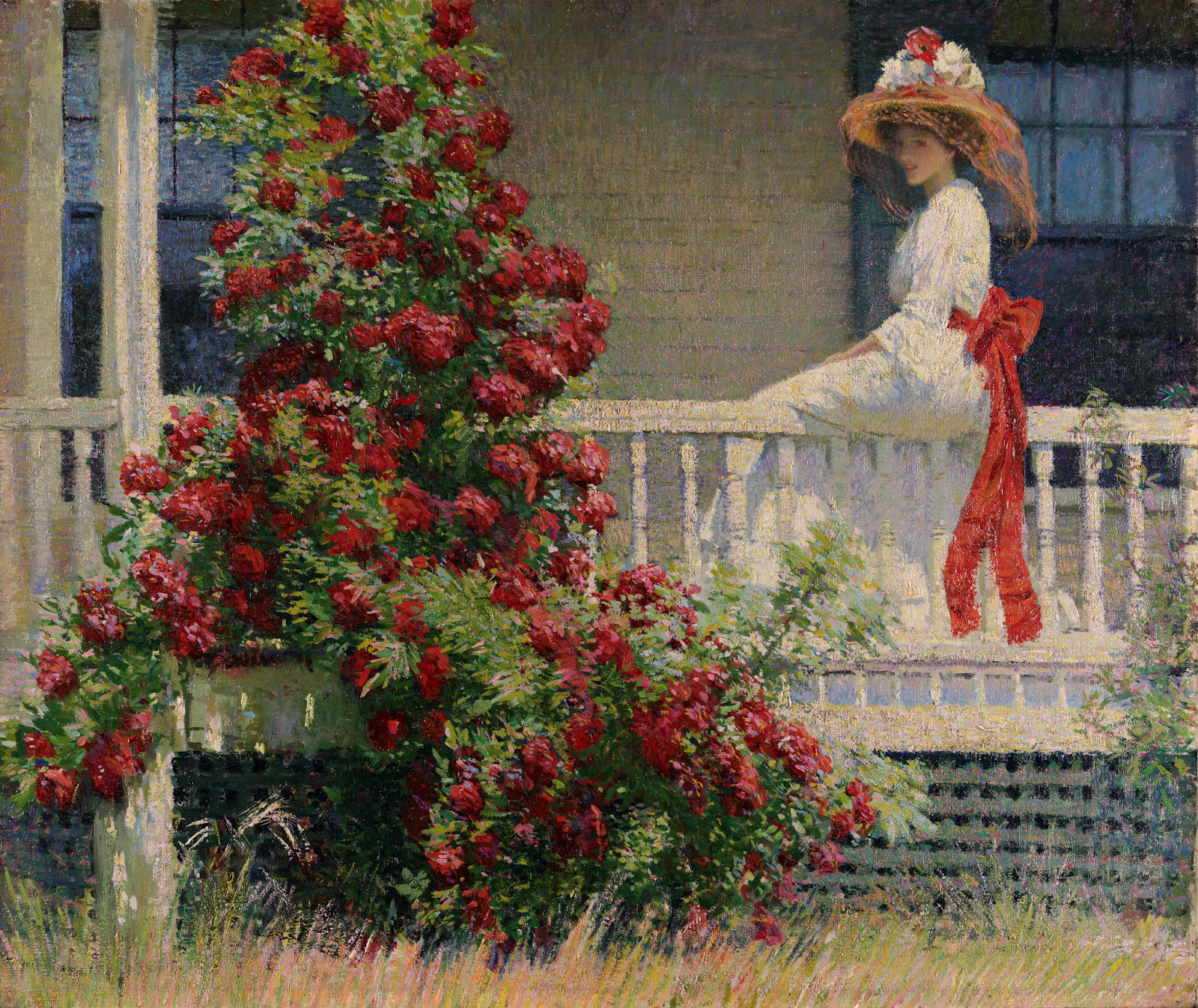

All these disparate factors combined to promote the Garden Movement as an ideal for America. Philip Leslie Hale's 1908 painting, The Crimson Rambler captured the mood to perfection. The vibrant young woman in the picture sits astride the porch fence, poised for growth and movement, just as the climbing rose bush - a variety only introduced in the U.S. during the 1890's - soars upward.

Hale (1865–1931) was a New Englander, a descendant of the Revolutionary War hero, Nathan Hale. If Philadelphia provided inspiration for the Garden Movement, many of the leading American Impressionist painters were from New England.

Of these, Frederick Childe Hassam (1859-1935) was the most commanding figure. Prodigiously talented and prolific in the number and variety of his paintings, Hassam was also a contradictory figure. Self-taught, he was a consummate professional. Hassam loved the quietude of New England seacoast refuges like Appledore Island, Maine, where he befriended the poet and gardener, Celia Thaxter. Yet he never tired of observing people in the supercharged atmosphere of the big cities.

"Humanity in motion,” Hassam declared, “is a continual study to me.”

Hassam's art was not without points of contradiction, too, and the influence of the Garden Movement, perhaps surprisingly, brought them to the surface.

Childe Hassam,The Goldfish Window, 1916

In The Gold Fish Window, 1916, Hassam painted a work of great beauty. Every detail of the scene, natural or man-made, is bathed in golden, luminous light. Yet there is total absence of the spontaneity and mobility that Hassam professed to find intriguing.

The Gold Fish Window is a disturbing picture. Its unsettling effect is compounded by the fact that Hassam painted many variations on the theme of a solitary young woman, meditating or melancholy. Like the goldfish swimming in their light-drenched bowl, the young woman is seemingly a hostage of her environment. The window frames, the bordering curtains, the polished table act as barriers to her interaction with the outside world. Even the garden, sun-dappled and flower strewn, is less of a sanctuary than a prison cell.

The young woman in The Gold Fish Window may be compared to the protagonists of Johannes Vermeer's works. Vermeer’s young women occupy a serene moment in time. Yet they are all absorbed in a task, making lace, reading or playing music. Hassam's young woman, by contrast, clutches a flower to her breast in an almost funereal gesture.

The Gold Fish Window was painted in 1916 while the Women's Suffrage Movement vigorously campaigned for the rights of women in the United States. You would never know it from The Gold Fish Window that Hassam had declared that a true artist is "one who paints the life he sees about him, and so makes a record of his own epoch.”

As we can see in the array of paintings in the PAFA exhibit, other painters of the era also placed pensive young women in their works. In 1918, Daniel Garber (1880–1958), the leader of the second generation of the New Hope Impressionists, countered this view of passive femininity. Garber’s The Orchard Window is a brilliant evocation of a young woman in harmony with nature and society.

Daniel Garber, The Orchard Window, 1918

By the 1920’s, however, American Impressionists like Garber were unable to maintain their place in the front ranks of Modernism. For all the revolutionary technique that Hassam, Garber and others brought to their work, American Impressionism was increasingly perceived as the art of the past.

These reflections deal with only one of the themes of PAFA exhibit, the Lady in the Garden. The Artist's Garden is wide-ranging and extremely perceptive in its presentation of vital developments in American life and culture. Additional themes treat the Urban Garden, Leisure and Labor in the American Garden and the Garden in Winter.

The idea of including winter scenes in the exhibit, the Garden at Rest, is particularly significant because it shows the sensitivity of these American artists to the cycles of nature, to the fundamental structure and the regenerative power of the natural world.

Of all the American Impressionists, none made a better case for the importance of the natural world than John Henry Twachtman (1853-1902). Born in Ohio, but a New Englander by choice, Twachtman infused the subtle tonalities of James McNeill Whistler into his seasonal landscapes, especially those depicting winter.

"I can see now how necessary it is to live always in the country—at all seasons of the year. We must have snow and lots of it. Never is nature more lovely than when it is snowing," Twachtman wrote, ". . . . That feeling of quiet and all nature is hushed to silence."

Abbott Handerson Thayer, Blue Jays in Winter, c. 1905-09

Abbott Handerson Thayer's Blue Jays in Winter is another testament to the rediscovery of the natural environment. Thayer (1849-1921), more famous for his paintings of angels and childhood innocence, produced this remarkable work for his book, Concealing Coloration in the Animal Kingdom.

Thayer's ideas on animal camouflage were disputed by no less a figure than Theodore Roosevelt. But the important point is that Thayer - and the rest of the American Impressionists - focused on nature as a living entity, a vital component of our daily lives.

Ultimately, the role of the artist as a vital interpreter of nature is the essential theme of this thoughtful exhibit. The Artist's Garden: American Impressionism and The Garden Movement, 1887—1920 will be on display at PAFA, February 13, 2015 - May 24, 2015. Following its presentation at PAFA, this wonderful exhibition will be shown at a number of other U.S. museums during 2015-2016.

And of course, the natural wonders depicted by Breck, Hassam, Garber, Twachtman and the other American Impressionists are also on view each time you look out the window on to your own garden or green space nearby.

***

Text: Copyright of Ed Voves, all rights reserved

Images Courtesy of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia.

Introductory Image Philip Leslie Hale (1865–1931), The Crimson Rambler, ca. 1908 Oil on canvas 25 1/4 x 30 3/16 in. Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Joseph E. Temple Fund, 1909.12

Cecilia Beaux (1855-1942), Landscape with Farm Building, Concarneau, France, 1888, Oil on canvas, 11 1/16 x 14 3/16 in. Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, Gift of Henry Sandwith Drinker, 1950.17.31

Thomas Shields Clarke, Series of approximately 100 photographic autochromes, ca. 1910 PAFA Archives

Bessie Potter Vonnoh (1872-1955), Water Lilies Fountain, 1913, Bronze, 28 ¾ x 15 ¼ x 7 ¼ in. Conner Rosenkranz, LLC Photo: Mark Ostrander, courtesy of Conner Rosenkranz, New York

John Leslie Breck (1860-1899), Garden at Giverny (In Monet’s Garden), between 1887-91 Oil on canvas, 18 x 21 7/8 in. Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Collection, 1999.18. Photo: © Terra Foundation for American Art, Chicago

Childe Hassam (1859-1935),The Goldfish Window, 1916, Oil on canvas, 34 3/8 x 50 5/8 in. Currier Museum of Art, Manchester, NH, Museum Purchase: Currier Funds, 1937.2

Daniel Garber (1880-1958), The Orchard Window, 1918, Oil on canvas, 56 7/16 x 52 ¼ in. Philadelphia Museum of Art, PA, Centennial gift of the family of Daniel Garber, 1976-216-1

Abbott Handerson Thayer (1849-1921), Blue Jays in Winter, study for book, Concealing Coloration in the Animal Kingdom, c. 1905-09, Oil on canvas, 22 1/8 x 18 1/8 in. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC, Gift of the heirs of Abbott Handerson Thayer 1950.2.12/Art Resource, NY

No comments:

Post a Comment