Art in a Time of Suffering

Reflections on Coping with the Covid-19 Crisis

By Ed Voves

Original Photography by Anne Lloyd

On Thursday afternoon, March 12, 2020, the Press Room of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City released a major communique. The headline proclaimed:

Metropolitan Museum to Close Temporarily Starting March 13

It was a shock to read this - but not a surprise. With the global spread of the Covid-19 virus and thousands of deaths already reported in China, Iran and Italy, it was only a matter of time before the disease reached the United States.

The press release quoted Daniel H. Weiss, the Met's President and CEO:

"The Met's priority is to protect and support our staff, volunteers, and visitors, and we have been taking several proactive precautionary measures, including discouraging travel to affected areas, implementing rigorous cleaning routines, and staying in close communication with New York City health officials and the Centers for Disease Control. While we don't have any confirmed cases connected to the Museum, we believe that we must do all that we can to ensure a safe and healthy environment for our community..."

It was a wise, caring and effective move. As Thursday afternoon wore on, more museums followed suit.

The next morning - Friday the 13th - more closings were announced and not just by art museums. "March Madness" was cancelled, despite earlier plans to play the exciting college basketball tournament without direct fan participation. Many of life's pleasures - creative or recreational endeavors which supply our lives with meaning - were being postponed or eliminated to prevent the spread of infection.

The ominous thought passed through my mind that this was how Sir Edward Grey, Britain's Foreign Secretary, must have felt during the last hours of peace in 1914.

"The lamps are going out all over Europe," Sir Edward exclaimed, "we shall not see them lit again in our life-time."

Reflecting on the daily, often hourly, updates on the globalization of Covid-19, I recalled a provocative 2014 exhibition at the Met. Death Becomes Her surveyed mourning apparel and funeral artifacts from the early 1800's to the twentieth century. Although medical science had begun to "conquer" some diseases during this period, other maladies, tuberculosis, cholera and the "Spanish" influenza of 1918, killed countless people all over the world.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2014) Gallery view of the Death Becomes Her exhibition, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Death Becomes Her, however, was not in the least morbid. The exhibition showed that people are resilient. The clothes they wear and their rituals during times of grief reflect the human ability to endure. Some of the "widow's weeds" on view were quiet stylish, for the most part those worn at the end of the grieving cycle, and striking funeral clothing for men and children was included in the exhibition. Life - and art - goes on.

None-the-less, a pandemic cannot easily be shrugged-off with comforting reflections on a fondly remembered art exhibit.

It has been increasingly difficult for me to focus on art, despite the embarrassment of riches, in terms of the many exhibitions planned for 2020. This year is the Metropolitan Museum of Art's 150th anniversary and a host of special programs and exhibitions are planned to celebrate this auspicious event. At the top of this list is Making the Met, a retrospective look at the landmark exhibits, inspired leadership and human drama at 82nd and Fifth Ave.

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Publicity image for Making the Met, 1870-2020. © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Big events at other museums are planned in 2020, as well, though I almost wrote about these in the past tense - "were planned."

Renovations at the Philadelphia Museum of Art are almost complete, with a ribbon-cutting and a big Jasper Johns exhibition set for the autumn. Thomas Eakins' The Gross Clinic, which the museum jointly owns with the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, will be back on display.

A fabulous Degas exhibit has just debuted at the National Gallery of Art in Washington. Another major exhibition, scheduled for May, A Superb Baroque: Art in Genoa, 1600–1750, has been postponed. Given the severe impact of the Covid-19 virus on Italy, it is likely to be a long wait before these rarely-seen (in the U.S.) Baroque masterpieces travel to D.C.

"Der mentsh trakht un Got lakht." How timely is this Yiddish proverb! Man plans and God laughs.

One of the essays planned for Art Eyewitness this spring was a follow-up to the review of Making Marvels, the Met’s exhibition of wondrous scientific instruments, automatons and other "gizmos" from the Renaissance to the Age of Enlightenment.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2019) Portable Sun Dial, made by Paulus Reinman, 1602

Works of art, as well as technological masterpieces, these "marvels" once graced the “cabinets of wonder” called Kunstkammern in Germanic-speaking realms.

These private art and science collections evolved into today's museums. The first truly public institution, the British Museum, was founded in 1759 by Sir Hans Sloane, an Irish-born physician with an insatiable appetite for collecting.

Admission ticket to the British Museum, 1790. ©Trustees of the British Museum

The rise of museums is an important topic and I had amassed fascinating information on how the transformation occurred. Yet, my thoughts kept heading along a different path, to reflections on the status of museums, now, in these dark moments of sickness and death, sorrow and fear.

On view in Making Marvels was an intriguing painting, entitled The Knight's Dream (1670) by Antonio de Pereda. Principally known as a master of still-life paintings, the Spanish-born Pereda painted an allegorical scene foreshadowing Francisco Goya's The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters (1799).

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2019) Detail of The Knight's Dream (1670) by Antonio de Pereda

In The Knight's Dream, a Spanish hidalgo, surrounded by the treasures of his "cabinet of wonders," dozes off. He is not haunted by “monsters” as in Goya’s print. Rather he is visited by a heavenly messenger whose banner bears a warning about the nature of time: "Eternally it stings, swiftly it flies and it kills."

It was a timely message – then and now. The curators of Making Marvels doubled the impact of this powerful work of art by displaying an astronomical table clock that is almost an exact duplicate of the one we see ticking away in the painting.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2019) Astronomical table clock, mid-17th century

By the time Pereda painted The Knight’s Dream in 1670, once mighty Spain’s political power was in rapid decline. The Spanish economy disintegrated as the silver shipments from its New World colonies decreased, leaving massive debts unpaid from vast expenditure on futile wars.

Spanish scholars, interested in the arts and sciences like the napping hidalgo, received little support from the bankrupt state. Some years prior to the creation of this symbolic work of art, a Spanish historian and poet living in Seville, Rodrigo Caro (1573-1647) wrote despairingly to a colleague, "I know not if you will find here in these unhappy times three men who occupy themselves with these studies …"

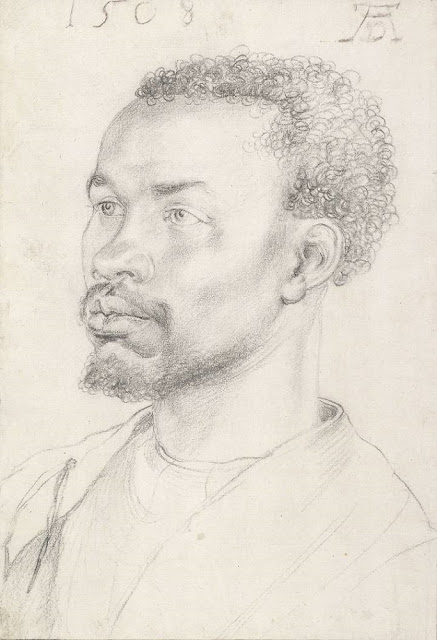

Edme de Boulonois. Juan Luis Vives, ca. 17th century

It was not always so. During the early Renaissance, Spain produced a number of outstanding humanist scholars. The most notable was Juan Luis Vives (1493-1540), whose writings on human memory and emotions laid the foundation for modern psychology. The city of Seville, birthplace of two of Spain’s greatest artists, Velázquez and Murillo, was a glittering, cosmopolitan center of culture.

Disaster struck Seville in 1646, with a devastating outbreak of plague, most likely a form of the bubonic plague or Black Death which had wiped out close to half of Europe’s population during the 1300’s. By the time it ended in 1652, an estimated 500,000 people perished in Seville and adjacent regions in southern Spain. Furthermore, there had been an earlier outbreak of plague in 1596 and it reoccurred in 1676, lasting until 1685. When Spanish deaths from its endless military campaigns are factored-in, it is no wonder that Spain’s political power and economic clout vanished during the late 1600’s.

But why did Spain’s culture go into an eclipse at the same time? A "golden age" of art and literature, of El Greco and Cervantes, had flourished during the opening decades of the seventeenth century. England also suffered major bouts of the plague during the late 1500’s and 1600’s, but English literature and science - and to a lesser extent art - continued on the upswing throughout the whole seventeenth century. The answer can be found by probing the identity of the "Invisible College."

By 1600, Spain appeared to have vastly outpaced England in the founding of universities. Spain had thirty. England had three. (Scotland's universities were a separate system.) The primary emphasis of Spain's universities, however was theology, law, philosophy and the classical medical theories of the Greeks and Romans. That was true, for most of the 1600's, at Oxford, Cambridge and Durham. The crucial difference was the development of an informal network of "Natural Philosophers" throughout England.

Over the course of the seventeenth century, these early English scientists began to organize groups with regular meetings and guiding precepts, based upon the ideas of Francis Bacon. Robert Boyle (1627-1691), one of the founders of the Royal Society in 1660, played a major role in helping to diffuse ideas and information, as well as formulating the methodology of scientific inquiry.

George Vertue, after Johann Kerseboom. Robert Boyle, 1739

Samuel Hartlib's "Comenian" circle, the Philosophical Society of Oxford, Gresham College (where Boyle was an active member) in London are some of the more well-known of these groups of natural philosophers. A remarkable woman, Lady Anne Conway (1631-1679), a patron of this "new" learning and a scientist herself, established her country estate as a research center for the Cambridge Platonists.

These free-thinking English scholars conducted experiments, published pamphlets and corresponded across the battle lines of the English Civil War and the Puritan Revolution. Their "Invisible College" enabled scholarship, science and literature in England to thrive at the same time as higher learning and cultural activities in Spain withered.

There is a special relevance of the contrasting fortunes of Spain and England during the 1600's to our present situation. The "Invisible College" which nurtured English genius during the tumultuous seventeenth century is available to us as we confront the Covid-19 pandemic and the political/social ramifications which are likely to occur as a consequence.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2020) Gallery view of Degas at the Opera at the National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C

As I write these words, art galleries all over the world stand empty. Thanks to the vision and generosity of museum administrators and curators, a vast array of digital resources is available to us during the Covid-19 crisis. Art museums, especially in the United States, have made thousands of images of paintings, drawings, sculptures and other works of art available for use via Creative Commons.

Many museum staffs have gone the extra mile by creating special web pages granting easy access to the research and home schooling textual content which is routinely uploaded on their web sites. What Juan Luis Vives, Robert Boyle and Anne Conway did long ago to assist their fellow natural philosophers, the behind-the-scenes curators and "techies" at our art museums are doing for us during the "plague year" of 2020.

The Met 360° Project. The Temple of Dendur © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

I don't wish to slight any museum curators for their efforts in sharing their collections via the Internet. However, since this is the Met's anniversary year, I am going to comment at some length on the riches to be found at www.metmuseum.org. First of all, even though the Met is closed, you can take a virtual tour of the museum via the Met 360° Project. Six videos, created by using spherical 360° technology, enable visitors to "virtually" visit selected sites at the Met, including the Temple of Dendur and the Cloisters.

The Met also introduces key works of art and new acquisitions on the Website with the Connections and the MetCollects series. In these engaging interviews, Met curators, conservators, educators, security officers, as well as collectors and artists, share their insights on iconic works of art.

In researching Art Eyewitness, I regularly use the Met’s invaluable Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Even though I spend a good bit of time on the Met's website, I have only scratched the surface. The resources, images and text, provided by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, enable us to continue to work and enjoy, protected from the threat of Covid-19. And what is true for the Met is true for the National Gallery of Art, the Philadelphia Museum of Art and other museums in the United States and other nations.

As I prepared to write this essay, I came across a search tool in the Met Digital Collections giving access to vintage photos of many of the great special exhibitions over the years at the Met. It was like being given a ticket to a time machine and I went a little crazy.

Many of the exhibition series have only a few pictures available, but there are 85 photos covering the 1983 blockbuster The Vatican Collections: The Papacy and Art. This incredible series, photographed by Al Mozell, shows the entire process of installing the exhibition - removing the art works from their wooden crates, building the exhibition set, positioning the statues on their pedestals, scenes of throngs of appreciative art lovers crowding the galleries.

Al Mozell, Photos (1983) The Vatican Collections: the Papacy & Art exhibition, © Metropolitan Museum of Art

I was one of the awe-struck visitors to the Vatican Collections exhibition. For me, it was like spending a day in the Vatican Museums, a Roman Holiday if you will.

Unlike my recent discovery of the exhibition photo site of the Met, I was aware of - and a frequent visitor to - a comparable digital picture archive of the Museum of Modern Art. There I discovered a photo of Audrey Hepburn visiting MOMA in 1957 for a Picasso exhibition. Ms. Hepburn is shown with Alfred H. Barr, the legendary founder of MOMA. I loved this photo from the minute I first saw it and I have kept it in reserve for my long-planned essay on the rise of art museums.

Barry Kramer, Photo (1957) Audrey Hepburn & Alfred H. Barr, at the MOMA exhibit,"Picasso: 75th Anniversary"

There is no time like the present. However, I am motivated to use this photo of Audrey Hepburn based on her life experience, rather than to illustrate an art history theme,

Recently, I read the compelling biography of Audrey Hepburn's early life, Dutch Girl, by Robert Matzen (GoodKnight Books/2019). Hepburn was no stranger to danger and suffering. As a teenager during World War II, she was a messenger for the Dutch resistance and was nearly killed in the Battle of Arnhem in September 1944 when rockets fired by a British aircraft at German tanks missed and exploded a few feet from where she stood.

After the Allies failed to capture a key bridge at Arnhem, the Nazis were able to halt the attack. The north of Holland, where most of the Dutch population lived, was cut-off without food. The "Hunger Winter" ensued, 20,000 people starved to death and many young people, Audrey Hepburn included, suffered the physical and emotional effects of this privation for the rest of their lives.

A visit to an art exhibition is a life-enhancing experience. So are all the joys of living. People like Audrey Hepburn, who survived several encounters with death, know this in their hearts and souls.

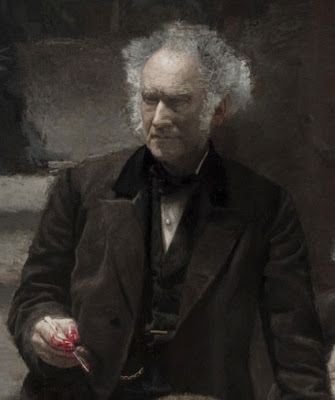

Naturally, human beings do not relish being reminded of the effects and after-effects of catastrophes. In closing, I am reminded of the response to Thomas Eakins' Gross Clinic, which I mentioned earlier. Eakins painted his heroic depiction of Dr. Samuel Gross, one of the pioneers of American medicine, for display in the Centennial Exhibition of 1876. His masterpiece was rejected. The American Civil War had ended only ten years before. The dark red oil paint dripping from Dr. Gross' fingers and surgical knife was too real, too close to the actual blood shed in the war.

Thomas Eakins, Portrait of Dr. Samuel D. Gross (The Gross Clinic), 1875

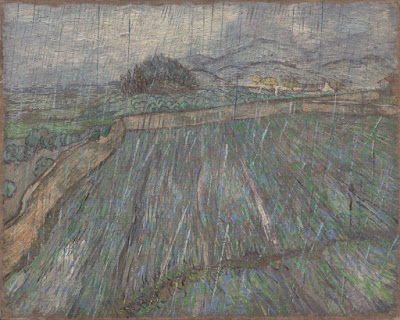

Great art is for the dark days as well as sunny afternoons. Artists paint their souls into their masterpieces. Sculptors carve the marrow of their being into theirs. When we draw comfort from works of art during times of suffering, the "blood, sweat and tears" of Van Gogh, Michelangelo, Rodin and all the rest are there for our asking.

At some point, the shadow of the Covid-19 pandemic will be lifted. Until then, thanks to the "Invisible College" provided by museum web sites, we can continue to draw inspiration from the works of art we so cherish.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2020) Gallery view of the Philadelphia Museum of Art

Hopefully, that happy day will soon come, making it is possible for art lovers to renew their kinship - for that is what it is -with the inspiring masters of great art. The experience, I think, will be even sweeter and more meaningful than before.

***

Text: Copyright of Ed Voves. Original Photos: Anne Lloyd. All rights reserved

Images courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, NYC, the National Portrait Gallery, London, and the British Museum

Introductory Image:

Thomas Eakins (American, 1844-1916) Portrait of Dr. Samuel D. Gross (The Gross Clinic) (detail), 1875. Full entry below.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2014) Gallery view of the Death Becomes Her exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC.

Metropolitan Museum of Art publicity image for the Making the Met, 1870-2020, exhibition. Copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2019) Portable Sun Dial, made by Paulus Reinman, 1602. Ivory, brass: 4 1/2 × 3 1/2 in. (11.4 × 8.9 cm) Metropolitan Museum of Art. Gift of Mrs. Stephen D. Tucker, 1903. # 03.21.24

Admission ticket to the British Museum, 1790. ©Trustees of the British Museum.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2019) Detail of The Knight's Dream (1670) by Antonio de Pereda y Salgado (Spanish, 1611-1678) Collection of Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, Spain.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2019) Astronomical table clock. From Augsburg, Germany, mid-17th century. Case: gilded brass and gilded copper; Dials: gilded brass and silver; Movement: brass, gilded brass, and steel: 25 × 10 × 10 in. (63.5 × 25.4 × 25.4 cm). Metropolitan museum of Art. Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917. # 17.190.747

Edme de Boulonois. Juan Lewis Vives, possibly late 17th century. Line engraving, 8 in. x 5 1/4 in. (204 mm x 132 mm) paper size. Given by the daughter of compiler William Fleming MD, Mary Elizabeth Stopford (née Fleming), 1931. National Portrait Gallery, London. NPG D24337

George Vertue, after Johann Kerseboom. Robert Boyle, 1739. Line engraving: 15 3/8 in. x 9 7/8 in. (391 mm x 250 mm) paper size. Acquired unknown source, 1953. National Portrait Gallery, London. NPG D32051

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2020) Gallery view of the Degas at the Opera exhibition at the National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

Metropolitan Museum of Art photo.The Met 360° Project, The Temple of Dendur. Copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC.

Al Mozell, Photos (1983) The Vatican Collections: The Papacy and Art. Exhibition Photographs: 2 x 2 inch slides. Metropolitan Museum of Art, Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts. Copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC.

Barry Kramer, Photo (1957) Audrey Hepburn and Alfred H. Barr, Jr. at the exhibition, "Picasso: 75th Anniversary". Photographic Archive - The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York. IN619.73. Copyright © The Museum of Modern Art, NYC.

Thomas Eakins (American, 1844-1916) Portrait of Dr. Samuel D. Gross (The Gross Clinic), 1875. Oil on canvas: 8 feet × 6 feet 6 inches (243.8 × 198.1 cm) Philadelphia Museum of Art/Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. # 2007-1-1

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2020) Gallery view of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Patrons are examining Sunflowers (1889) by Vincent van Gogh in Gallery 261, the Resnick Rotunda. Van Gogh's Portrait of Madame Augustine Roulin and Baby Marcelle (1888) is at right.