William Hogarth - The Printmaker's Progress

An Art Eyewitness Essay

By Ed Voves

Original photos by Anne Lloyd

When the National Gallery in London was founded in 1824, its collection consisted of 38 paintings. These had been amassed by the financier, John Julius Angerstein, and then purchased by the British government when he died. Angerstein (1735–1823) had favored Old Master artists, Claude Lorrain, Anthony van Dyck, Rembrandt and Raphael. Hardly any works by British painters had graced the walls of his London town house.

There was only one British painter whom Angerstein esteemed on a par with Claude and van Dyck: William Hogarth.

Self-taught genius. Master printer and gifted painter. Chronicler of "modern moral subjects." Generous benefactor of noble causes, yet a man with no illusions. William Hogarth (1697-1764) was all of these.

Hogarth was also a great "contrarian" and a rebel against the stranglehold of foreign Old Masters on British art. He famously denounced wealthy English visitors to Italy for purchasing "dead Christs, holy families, Madonnas, and other dismal dark objects."

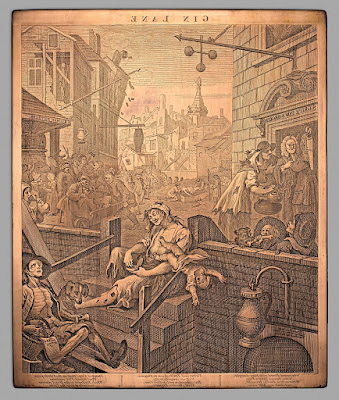

Exhibitions of Hogarth's works are comparatively rare, especially in the United States I have only been to one, presented by the Morgan Library and Museum in 2019. Entitled Hogarth: Cruelty and Humor, the exhibition was based on the Morgan's trove of preparatory drawings of Hogarth's prints issued in 1751, Gin Lane and Beer Street, and The Four Stages of Cruelty.

Although brilliantly curated, Hogarth: Cruelty and Humor was not an exhibit which induced me to linger in the gallery. Gin Lane and The Four Stages of Cruelty were unsparing critiques of the dark side of British society. Although Beer Street supplied a touch of humor, the emphasis on depravity was unsettling. Though motivated to correct glaring social vices, these prints reveal only one aspect of Hogarth's personality. As a result, I elected not to review this Morgan exhibit.

Hogarth embraced life in all of its "humors." This we can see in his magnificent print, Southwark Fair (1733).

The whole human comedy/drama is represented here. Street brawlers and acrobats, a pickpocket next to a peep show, a beautiful young drummer girl attracting a bevy of admirers while a lonely, unappreciated bagpiper is about to be struck by actors tumbling down from a crashing stage.

Cruelty or humor?

How then to comprehend and appreciate William Hogarth? This little man (his height was just under five feet) was a towering figure during his lifetime and has grown in "stature" over time. This is especially true in the post-World War II era thanks to the devoted scholarship of Ronald Paulson. Several popular biographies have also served Hogarth well, including the recent Hogarth: Life in Progress by Jacqueline Riding (2021).

Despite the impressive quality of these modern-day resources, it was a unique opportunity to study the 1822 edition of Hogarth's collected prints, in the collection of the Free Library of Philadelphia, which enabled me to gain the measure of this amazing man and artist.

Thanks to Ms. Alina Josan, librarian for the Art Department of the Free Library, I was able to closely study The Works of William Hogarth, reprinted from the original plates. The whole course of Hogarth's life and work was placed before us on the library table, enabling my wife Anne to take an array of close-up photos of these fantastic prints.

It is a rare occasion to be granted hands-on access to a historic volume like this. An "elephant folio" in size, two centuries-old and, despite wear-and-tear on the covers, its pages are in magnificent condition. Anne and I were granted a time-travel ticket to Hogarth's world. Finally, I had the chance to grasp Hogarth's ideas and ideals, and to appreciate his skill as a media-savvy artist.

When Hogarth died in 1764, control of his prints and printer's plates went to his capable widow. Jane Hogarth eventually sold the plates to the prestigious printseller, John Boydell. In 1790, Boydell published The Original Work of William Hogarth. It was a magnificent endeavor, worthy of Hogarth himself.

Boydell was not content to merely reprint Hogarth's existing prints but also commissioned new engravings of several Hogarth works to present as complete a record of the revered artist's life as was possible. Detailed commentary on each of Hogarth's works in the book was provided by a noted art writer, John Nichols.

In 1818, the publisher Baldwin, Cradock and Joy purchased Hogarth's plates and had them restored by the engraver James Heath. These were used to publish the 1822 edition which Ms. Josan “wrestled” from the storage vaults of the Free Library, so that I could appreciate Hogarth’s artistic achievement.

The print quality of the 1822 edition is astonishing, permitting minute examination of Hogarth's technical skill in drawing and engraving. Hogarth was a master of the hatching process, by which black, white and gray "color" tones were imparted to his prints. He also had an incredible eye for the effect of light. His talent in both respects can be seen in his 1733 print, A Midnight Modern Conversation.

Notice the reflection of a window, lit by the light of dawn, on the brandy decanter in the hand of the befuddled drinker. On the table close by is an overturned candle stick.

Detail of William Hogarth's A Midnight Modern Conversation

With this small detail, Hogarth makes a telling point in this lampoon of tipsy gentlemen "deep in their cups." They have drunk the night away.

Over the course of the nineteenth century, the plates of the 1822 edition were used and reused until the print quality was negligible. This over-exposure, along with the bawdy details of many of Hogarth’s pictures, led to a partial eclipse of his reputation. A number of “eminent Victorians,” however, continued to uphold Hogarth’s creative genius. Charles Dickens was a huge admirer. The walls of his study were lined with Hogarth prints.

The best way to appreciate Hogarth’s place in the realm of art is to study his prints. Hogarth was first and foremost an engraver and a printmaker. He trained in this profession as a youth and worked his way from engraving business cards to creating original series of illustrated stories, such as A Harlot's Progress (1731-32), which gained him fame and fortune.

Later in his career, Hogarth commissioned other artisans to do some of the labor involved in preparing the copper plates for his prints. This enabled Hogarth to devote more time to painting the original versions of new "progresses" like the series, Marriage A-la-Mode, as well as portraits and large biblical scenes for charitable institutions like London's Foundling Hospital. Even so, Hogarth remained an engraver/printmaker at heart, reserving for his own hand the expressive facial features of the protagonists of his prints.

Hogarth was extremely zealous in promoting and selling his prints and paintings. He endeavored to do so by his own efforts, rather than depend on agents or auction houses. Occasionally, he made a misstep in his marketing strategy. But the memory of the terrible poverty of his childhood and his father's imprisonment for debt drove him to rely on his own talents and to work without respite.

One of the key details of Hogarth's prints is the statement "Published by Act of Parliament" which appears along the bottom of his prints beginning in 1735.

Infuriated at the way that rival printers were pirating pictures like A Midnight Modern Conversation and his series, A Harlot's Progress. Hogarth petitioned Parliament to enact legislation to protect his work and that of other legitimate artists. In 1735, Parliament passed the landmark bill, Engravers' Copyright Act (8 Geo.2 c.13). "Hogarth's Act" as it became universally known, remains the foundation of modern copyright protection law.

The opportunity to closely study the splendid 1822 edition of Hogarth's prints enabled me to ponder a question concerning Hogarth's painted and printed versions. When a painting or drawing is engraved and then printed, the result is a mirror image of the original. Which is the stronger, more engaging version?

Several years ago, I had the chance to examine the Marriage A-la-Mode paintings at the National Gallery in London (Angerstein had bought the whole series).The arrangement and orientation of the printed versions, which I had seen seen in art books, seemed more effective than the painted originals. But given the reduced size of the book illustrations, it was difficult to reach a conclusion.

After studying the full-sized prints in the 1822 book, I think that Hogarth painted the originals with the "layout" of the intended print versions definitely in mind. Hogarth's paintings are superb works of art in their own right. That being said, when his paintings and prints are compared in terms of narrative movement, the verdict - in my estimation - is clear. The prints are stronger.

Earlier in his career, Hogarth created book illustrations which would have been viewed left-to-right, just as the text in books is "read." When painting the initial images of A Harlot's Progress, The Rake's Progress and Marriage A-la-Mode, Hogarth kept this matter of perception in mind. He generally configured the action in the paintings to insure that the printed versions would be viewed in the accustomed style, left-to-right.

I closely studied numerous prints in the 1822 edition, cross-referencing them to illustrations of Hogarth's paintings. No matter how impressive the paintings are as independent works of art, the narrative flow of the prints is superior. Moreover, there is a real sense of a continuum in each print series. A story, a human drama, unfolds in each of these episodic "progresses," carrying us to the tragic, unforgettable denouement.

These reflections hold-true for Hogarth's one-off pictures, as well as the "progress" series.

A good example is the hugely comedic, Morning (1738).This was the first of a set of paintings called The Four Times of the Day. Hogarth created these for his friend, Jonathan Tyers, the impresario of the Vauxhall Gardens, London's premier resort. These paintings/prints depicted street scenes at different hours of the day and different seasons. The characters appear only once, unlike the protagonists of the "progresses."

In Morning, a prudish spinster, clad in a fashionable yellow dress is intent on "keeping-up-appearances." Despite the freezing cold and snow, she is marching-off to church, St. Paul's in Covent Garden, without a cape or coat. Her shivering page boy trudges behind her, carrying her prayer book under his arm, his cold-numbed hands stuffed in his jacket and pocket.

The improbable pair is halted in their tracks by revelers carousing outside the door of an infamous dive, Tom King's Coffee House. These libertines are obviously not intent on keeping holy the sabbath and the look of consternation on the spinster's face is priceless.

Once again, the printed version is more effective in conveying the sense of narrative flow, left-to-right. Hogarth, despite the pride he felt for his paintings, knew that many, many more people would see - and buy - his prints. That is why he concentrated his prodigious creative energies, talent and insight on the design of the prints.

Hogarth demonstrated a virtuoso's skill in painting and printmaking. Yet his achievement does not stop there. It needs to be emphasized that Hogarth was creating a new form of visual story-telling, which in time would lead to cinema and graphic novels.

The magnitude of Hogarth's innovations was grasped early on. William Hazlitt (1776-1830) considered Hogarth's compositions to be Epic Pictures. Hazlitt's commentary is worth quoting at some length.

His works represent the manners and humours of mankind in action, and their characters by varied expression. Everything in his pictures has life and motion in it. Not only does the business of the scene never stand still, but every feature and muscle is put into full play: the exact feeling of the moment is brought out, and carried to its utmost height, and then instantly seized and stamped on the canvas for ever.

Hogarth's achievements are all the more impressive when it is recalled how little he had to inform his efforts. There were no art museums in early 18th century London, just a few print shops selling Dutch genre scenes. We know that Hogarth studied the mural depictions of the life of St. Paul in London's new cathedral, but the primary sources of his unprecedented "progresses" were his own keen vision and retentive memory.

Hogarth's drawing ability is evidenced by surviving sketches. He also created a system of mental note-taking and devised hieroglyph symbols, abstract combinations of lines and curls, to help jog his memory. Often, these were unneeded, as the power of his observation and ability to recall incidents of interest were phenomenal.

Hogarth was, undeniably, a genius. But there was another creative spark, outside the limited realm of the British art scene, which helped ignite his spectacular success.

On the night of January 29, 1728, John Gay's The Beggar's Opera debuted at the Lincoln's Inn Fields Theatre. This musical play struck British society like a double broadside of cannons of a ship-of-the-line. With the first volley, Gay aimed the guns of his satire at the conniving "screen master general, Prime Minister Robert Walpole. The second was directed at London's cultural savants who favored Italian opera companies at the expense of native English talent.

Hogarth was in the audience of The Beggar's Opera, as we know from a sketch of the climax of the play. This shows the two heroines, Lucy Lockit and Polly Peachum, begging for the highway robber hero, Captain Macheath, to be spared from the gallows.

This sketch served as the template for Hogarth to attempt an ambitious effort in painting with oils, at which he was still inexperienced. (There are several drops of oil paint on the sketch.) Hogarth painted the celebrated scene from the play's third act several times, his skill in handling oil paint and pictorial composition gaining in strength with each effort.The version below, in the collection of the Yale Center for British Art, was painted in 1729.

The Beggar's Opera struck a chord with Hogarth, whose political views were much like Gay's. Far more importantly, The Beggar's Opera phenomenon encouraged Hogarth to launch the first of his series, A Harlot's Progress. What Gay did with dialog and song, Hogarth would do with pictures.

Hogarth's The Beggar's Opera was his first major success as a painter. Yet, oddly, he did not make an engraving of this very impressive work. As a result, the British public remained unaware that Hogarth had painted the climax of Gay's play, an audience favorite for decades after its 1728 debut.

When Boydell started the process of publishing the huge folio edition of Hogarth's prints, he correctly saw the gap in the timeline of the artist's creative development. Boydell decided to commission an engraving after this vital work by Hogarth to include in The Original Work of William Hogarth. By what can only be described as an act of providential grace, Boydell assigned the job to another William, William Blake.

Blake's engraving of the Beggar's Opera climax is a sensational work of art, in its own right, as well as a mighty tribute to Hogarth. Art scholars regard it as a high point of Blakes's early career, along with his famous depiction of Chaucer's Canterbury Tales.

This print, however, marks a point of departure in Blake's style from Hogarth's. Boydell did not commission any further engravings after Hogarth from Blake, who would soon devote his talents and energy to his own artistic vision utterly different from that of Hogarth.

Hogarth would, I think, have approved Blake's decision to follow his own muse, to blaze his own path through life and stick to it, regardless of the personal cost.

In her superb new biography mentioned above, Hogarth: Life in Progress, Jacqueline Riding writes about Hogarth's approach to art and of life. For Hogarth this meant "life in the raw" rather than conforming to stale conventions of copying plaster casts and reworking allegorical motifs:

The combining of the elegant with the grotesque is precisely why Hogarth's work challenges, jars even ... and why he is so innovative and unusual. It is this combination that sets him and his paintings apart: a refusal to see humour and the repugnant as separate from the great highs as well as the lows of human experience.

Perhaps the purest expression of Hogarth's celebration of the raucous London he loved is The Enraged Musician. This 1741 print was based on a monochrome oil sketch (as distinct from a full-color painting) and was a companion to another scene of life impinging on art, The Distressed Poet.

One may sympathize with the musician as he tries to practice. A squawking parrot, a barking dog, a bawling infant, a little drummer boy and an oboe-playing gypsy, a milkmaid singing her sales melody while a knife-sharpener grinds the blade of a meat cleaver. What is a man of culture to do?

There is no doubt what Hogarth would had advised the musician to do. Keep the window open and start playing. Add your tune to the music of the street, to the song of life.

That is what Hogarth did with his paintings and engravings which, thanks to the magnificent 1822 volume in the Free Library collection, I was able to study and thoroughly enjoy. For a wonderful few hours, The Works of William Hogarth transported me back to London of long ago and to an exultation of life that can be embraced this very minute.

***

Text: Copyright of Ed Voves, all rights reserved. Original photos copyright of Anne Lloyd, all rights reserved. Permission to photograph images from the 1822 edition of William Hogarth's prints, courtesy of the Art Department of the Free Library of Philadelphia

Introductory Image: Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) Portrait of the Painter and his Pug, (painting by William Hogarth, 1745), engraved in 1795 by Benjamin Smith for John and Josiah Smith, publishers, London. From The Works of William Hogarth, 1822.