Reviewed by Ed Voves

In the February 1878 issue of The Nation, the publication's art critic reviewed the annual exhibition of the American Water-Color Society (AWS). One of the members of the AWS was Winslow Homer, famous as a war artist during the Civil War and now a leader among American watercolor painters. The art critic's assessment of Homer was extraordinarily perceptive:

The always unexpected Mr. Homer, so certain to do something that nobody could have anticipated and that no inferior artist could do...

The Metropolitan Museum of Art has recently opened a new exhibition, Winslow Homer: Crosscurrents. The splendid array of 88 oil paintings and watercolors on view abundantly confirm Homer's status as one of America's greatest - and strikingly unconventional - artists. Focusing on one of the Met's signature works, The Gulf Stream, the exhibition makes a convincing case for Homer as a visionary painter with a strong social conscience.

Ed Voves, Photo (2022) Gallery view of Winslow Homer: Crosscurrents at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

A just-published biography, Winslow Homer: American Passage by Wlliam R. Cross (Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 550 pages), provides much-needed detail to bolster this image of the great American artist. Together, the Met's exhibit and the new biography certainly help us to better understand Winslow Homer the man. Yet, despite the excellence of exhibition and book, the "always unexpected Mr. Homer" remains the ellusive, enigmatic Mr. Homer.

Winslow Homer (1836-1910) was born in Boston just as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Margaret Fuller and Henry David Thoreau launched the intellectual revolution known as Transcendentalism. Homer's family had only modest financial resources. This made Emerson's credo of "Self-Reliance" a necessity for Homer rather than a highminded style of living.

From early in his childhood, Homer demonsrated a remarkable skill in drawing. Just as he entered his teenage years, commercial opportunity beckoned. The newly devised lithograph process expanded the ablity to reproduce pictures for the mass-market publications being established in the U.S. during the 1850's. Homer's proficiency in drawing and designing for lithographs gained him commissions from Harper's Weekly, the New York-based journal which quickly came to dominate the American news industry.

So successful was the young artist from Boston that Harper's offered Homer one of its prestigious positions as a staff artist in 1860. With a regular salary and the cachet of Harper's name on his resume, Homer had scored a degree of professional success which was truly impressive.

And then, the "always unexpected Mr. Homer" confounded expectations. He rejected Harper's offer and set himself up as a freelance artist. He explained his audacious decision as being based on his "taste of freedom... I have had no master, and never shall have any."

Homer traveled to the front lines in early 1862 as the Union army struggled to advance toward Richmond, Virginia, capital of the insurgent Confederate States of America. Homer visited an elite unit of the Army of the Potomic, Berdan's Sharpshooters, and sent back a drawing to Harper's which appeared in its November 15, 1862 issue.

A Sharp-Shooter on Picket Duty was just the picture which readers in the North wanted to see: a combat-tested marksman, armed with the most advanced rifle of the day. The engraving testified to Union's willpower - and firepower - to achieve victory.

That sentiment was not what Homer privately thought about the matter.

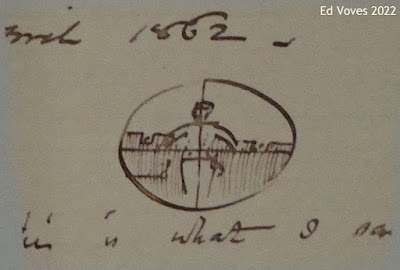

When Homer interviewed the actual troopers of Berdan's regiment, they handed him one of their rifles so that he could peer through its telescopic sight. Through its lense, he could see a Confederate soldier stationed on the opposing side of the battle line. Homer was unnerved by the experience.

Homer's Civil War paintings, including a version of Sharp-shooter in oils, occupy a prominent place in the opening gallery of the Met exhibit. These include Prisoners from the Front, painted soon after the war ended in 1865. It was Homer's first "old master" caliber painting. Yet, this and his other war pictures proved to be a problematic achievement.

For nearly three decades after the Confederate surrender, paintings related to the war remained out of favor. Overwhelmed by the scale of the watime tragedy - an estimated 750,000 military deaths and uncounted civilian casualties - Americans wanted to forget. But the source of pain, like the sensation of an amputated leg or arm, remained.

Homer needed to find a way to address this unspoken calamity and help his fellow Americans to rebuild their lives and their nation. Homer brilliantly succeeded, using an "unexpected" theme to do so.

From witnessing impressions as "near murder as anything I ever could think of," Homer turned to recording the lives of children and young people. Humanity's life force, its joys and its challenges, was celebrated by Homer in oil paintings and watercolors that have come to be cherished as some of America's most beloved pictures.

On the surface, paintings like Crossing the Pasture are exercises in nostalgia, depictions of childhood "innocence." There are certainly elements of "fond recall" in this wonderful painting, including personal memories. Homer maintained cordial relations with his own brothers, especially his older brother, Charles. But there was much more at work in this painting than merely hearkening back to boyhood memories.

Crossing the Pasture was painted in 1871-72. The date and the ages of the two boys are significant. The elder boy, carrying a switch to scare-off a menacing bull (not seen in this detail of the painting) is ten or eleven years old. He would have been born around the time of the Battle of Bull Run, the first great engagement of the war. The younger is aged about five or six years in age. His birth would have occurred around the time of General Lee's surrender at Appomattox.

The two boys in Crossing the Pasture, almost certainly brothers, might well be war orphans. But even if their father returned from the war, he was likely to have been crippled or emotionally shattered. Hundreds of thousands of Civil War vets, North and South, never fully recovered from their experience of combat.

These two youths live in a world largely devoid of older men. Despite the green fields and mountain air of Crossing the Pasture, the boys must make their way unaided through the first stages of life, confronting dangers with courage and mutual support.

The same is true for the girls and young women painted by Homer during the years following the Civil War - and Homer painted a lot of them. The war had opened the doors of economic and social opportunity to women, earning them widespread esteem. Though Homer never married, he held women in great respect, partly based on his affectionate relationship with his mother, a talented amateur artist.

Homer's young women are vigorous, self-reliant, not afraid to take risks. The protagonists in Eagle Head, Manchester, Massachusetts (High Tide) are anything but "shrinking violets." Yet, like the boys in Crossing the Pasture, the young women in Eagle Head live in decimated society. Men of their age are little in evidence. The military conflict is over but the "inner Civil War" stiil lingers on.

If an air of melancholy pervades many of Homer's paintings of children and young womanhood, he had achieved an admirable sense of emotional stability in several paintings created duiring the early 1870's. This balance was especially noticeable in works with a nautical theme. In outstanding paintings like Breezing Up, Homer evoked images of a harmonious, cooperative society.

Breezing Up, painted in 1876, the centennial year of America's independence from Great Britain, shows a catboat with a plucky crew of young boys and an older man, expertly sailing through choppy water. This is a vision of an America on course to greatness.

Dangers, however, lurked beneath the waves. Despite his great 1870's success, Homer's mood began to darken.

n 1883, Homer witnessed the rescue of two women, caught in the undertow of the surf at the the resort of Atlantic City, New Jersey. The endangered women in his painting of the event might well be two of the protagonists from Eagle Head. This time they are rescured by heroic, well-muscled life guards, who had been absent from the earlier canvas.

During the 1880's, there was a growing trend to depict heroic male figures, as in the popular frontier paintings of Frederic Remington. This is not likely to have been Homer's primary intention with Undertow.

Homer had just returned from an extended two-year stay at a remote English fishing community when he observed the near-tragedy at Atlantic City. The experience of living in the village of Cullercoats, on the edge of the menacing North Sea, marked an important point of tranistion for the visiting American.

At Cullercoats, Homer painted a series of astonishing watercolors of strong women, wives, mothers and daughters of the fishermen who braved the cold, dangerous sea to earn their living. His theme with incredible pictures like Inside the Bar was the struggle of life, the often unequal confrontation of humanity with nature.

In Breezing Up and other 1870's paintings, the protagonists of Homer's pictures seemed to be holding their own in the epic contest of human existence. The admirable fortitude of the Cullercoats "fishwives" continued the battle, with brave women and men still - if barely - winning. But with Undertow in 1883, the tide of fate, literally, began to change.

Death was cheated of victory in Undertow - this time. Two years later, Homer painted three works, two in oils, the other a watercolor study, in which human survival is anything but assured.

The first work, The Fog Warning (Halibut Fshing) shows a Grand Banks fisherman rowing his catch-laden dory back to the fishing schooner as fog begins to settle over the sea. Two ominous "fingers" of the fog bank, rising in the sky, command his attention. Unless he can reach the schooner before the fog completely shrouds the sky, he will be doomed, as is the case in the second painting of the series, Lost on the Grand Banks.

The peril faciing the Grand Banks fishermen is made even more explicit in the 1885 watercolor, Sharks (the Derelict). A dismasted schooner, adrift in tropical waters, is being swarmed by a school of sharks. There is no sign of the crew. Have they been saved by a distant ship, barely visible on the horizon or have they met a grisley fate?

Homer kept the watercolor for future reference. All the while, the existential struggle of human beings with nature, and by extention with modern industrial society, was reflected in his paintings.

As the last decade of the nineteenth century progressed, Homer painted numerous seascapes, filled with surging waves and lashing sprays of salty foam. Then in 1899, Homer returned to Sharks (the Derelict) as he prepared to paint what many believe is his greatest masterpiece, The Gulf Stream.

Many of Homer's late-career seascapes show no trace of human beings, as is the case with Sharks (the Derelict). In The Gulf Stream, Homer has placed Man in all of his tragic nobility back on the center stage of the canvas. Moreover, this soletary hero is an African-American sailor, as classically proportioned as any Greek hero in Hellenistic art.

The backstory of The Gulf Stream is brilliantly surveyed in the new biography, mentioned above, Winslow Homer: American Passage by Wlliam R. Cross. As the book and the Met exhibit testify, Homer portrayed African-Americans in many pictures with a degree of respect and honesty rare for the late 1800's. But with The Gulf Stream, Homer transcended his earlier, positive appreciations of the humanity of African-Americans by making the imperiled sailor a stand-in for all human beings. He is Everyman.

The late 1890's were the heyday of Symbolism in art. Certainly, The Gulf Stream can be appreciated as an exploration of the mysteries of life and death. There are traces of Homer's personal life in the picture, as well. His father had died recently and his own health was beginning to fail. Mortality was knocking on his door.

Homer, in his later years, lived in difficult times. Like the fisherman in The Fog Warning, he was rowing against the tide, in his case, of current social events. I feel that that harsh economic conditions, beginning with the Crash of 1873, must have affected Homer's sensitive spirit. Likewise, the hopes of a "new birth of freedom" were fading as Reconstruction was curtailed in 1877.

In 1893, during the gestation-period of The Gulf Stream, Homer painted The Fox Hunt. It is his biggest canvas, a fascinating, if bleak, view of nature oblivious of man or civilization. Yet the theme of Foxhunt is the same as in Homer's paintings with human protagonists. Life is a struggle. A hungry fox, floundering in the snow, is being pursued by equally hungry crows. The predator has become the prey.

The Fox Hunt has been described as a Darwinian "survival of the fittest" picture. If combined with some of his other late career works, including The Gulf Stream, a case could be made that the aging Homer had surrendered to world-weary despair.

However, Winslow Homer: Crosscurrents at the Met offers abundant evidence that far from resigning himself to fate, or hiding away from the world, this great American artist embraced life's experiences, in fair wind and foul weather.

Throughout his life, Winslow Homer was energized by the struggle of life, not repulsed by it. He waited until the beaches cleared of summer tourists and as the sea boomed and the ocean spray splattered him, he propped-up his easel.

Then Homer set to work, creating clear-eyed impressions of the natural world - as he saw it. These views we can still appreciate today, provided we are willing to look and to see and to feel with a degree of honesty equal to his.

***

Text and photos: Copyright of Ed Voves, all rights reserved. Original Photos: Copyright of Anne Lloyd

Images courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Introductory Image: Winslow Homer (American, 1836–1910) The Gulf Stream (Detail), 1899

Ed Voves, Photo (2022) Gallery view of the Winslow Homer: Crosscurrents exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Thomas A. Gray (American, active 1860's) Portrait Photo of Winslow Homer, 1863. Albumen silver print: Image/Sheet: 9.4 x 5.6cm (3 11/16 x 2 3/16") National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

After Winslow Homer. The Army of the Potomac - A Sharp-Shooter on Picket Duty (from Harper's Weekly, Vol. VII, November 15, 1862) Wood engraving: 9 1/8 x 13 3/4 in. (23.1 x 35 cm.) Metropolitan Museum of Art. Harris Brisbane Dick Fund. #29:88.3(5).

Metropolitan Museum of Art exhibit wall-text. Letter from Winslow Homer to George G. Briggs, 1896. Drawing shows Homer's view of a Confederate soldier through the telescopic sight of a sharpshooting rifle, 1862.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) Winslow Homer's Crossing the Pasture (Detail), 1871–72. Oil on canvas: 26 1/4 × 38 in. (66.7 × 96.5 cm) Amon Carter Museum of American Art, #1976.37

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) Winslow Homer's Eagle Head, Manchester, Massachusetts (High Tide)(Detail), 1870. Oil on canvas: 26 x 38 in. (66 x 96.5 cm) The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Mrs. William F. Milton, 1923. # 23.77.2

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) Winslow Homer's Breezing Up (A Fair Wind), 1876. Oil on canvas: height: 61.5 cm (24.2 in); width: 97 cm (38.1 in) National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. #1943.13.1

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) Winslow Homer's Inside the Bar (Detail), 1883. Watercolor and graphite on off-white wove paper: 16 x 29 in. (40.6 x 73.7 cm) The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Louise Ryals Arkell, in memory of Bartlett Arkell, 1954. #54.183

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) Winslow Homer"s The Fog Warning (Halibut Fishing), 1885. Oil on canvas: 30 1/4 x 48 1/2 in. (76.83 x 123.19 cm). Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. #94.72

Winslow Homer (American, 1836–1910) Sharks (the Derelict), 1885. Watercolor over graphite on wove paper: 14 1/2 x 20 15/16 in. (36.8 x 53.2 cm.) Brooklyn Museum of Art. #78.151.4

Winslow Homer (American, 1836–1910) The Gulf Stream, 1899. Oil on canvas: 28 1/8 x 49 1/8 in. (71.4 x 124.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Catharine Lorillard Wolfe Collection, Wolfe Fund, 1906. # 06.1234

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) Gallery view of the Winslow Homer: Crosscurrents exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, showing Homer's The Foxhunt from the collection of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) Winslow Homer's Northeaster, 1895; reworked by 1901. Oil on canvas: 34 1/2 x 50 in. (87.6 x 127 cm) The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of George A. Hearn, 1910. #: 10.64.5

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) Winslow Homer's Early Morning After a Storm at Sea, 1900–1903.Oil on canvas: 30 1/4 x 50 in. (76.8 x 127 cm) The Cleveland Museum of Art, Gift of J. H. Wade (1924.195)