Charlotte Brontë: An Independent Will

The Morgan Library and Museum

September 9, 2016 through January 2, 2017

Reviewed by Ed Voves and Anne Lloyd

Charlotte Brontë's life was like a Victorian "three-decker" novel. Her incredible rise from obscurity to become a literary sensation with the publication of Jane Eyre in 1847 was followed by staggering family tragedies, then marriage, brief happiness and early death in 1855.

What sounds like the plot of one of her novels was actually Charlotte Brontë's path to immortality.

The Morgan Library and Museum in New York City has organized an exhibition in honor of the bicentennial of Brontë's birth. With the cooperation of the Brontë Parsonage Museum in Haworth, Yorkshire, and the National Portrait Gallery and the British Library in London, the Morgan's exhibit is worthy of Brontë's life and achievement. Charlotte Brontë: An Independent Will sets a standard of curatorial excellence that will be hard to top.

Earlier this year, I reviewed part of this exhibition as it appeared at the National Portrait Gallery. The Morgan's exhibit, drawing upon three international famed institutions, is vaster in scale and superlative in the quality of the objects on display.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2016) Detail of the Richmond Portrait (1850) by George Richmond

In the earlier post, I focused upon the 1850 portrait of Charlotte Brontë, created by George Richmond. It was a gift to Bronte's father, Patrick, from her publisher, George Smith. In this review, I will comment upon several of the other Brontë treasures on view in the spectacular exhibit at the Morgan.

Born two hundred years ago in 1816, Charlotte Brontë was a product of what used to be dismissively referred to as England's "Celtic Fringe." Her father, the Rev. Patrick Brontë was born in Ireland in 1777, while her mother's family came from Cornwall. Charlotte Brontë was also a strong-willed Yorkshire woman at a time when the northern regions of England were the epicenter of the Industrial Revolution. She also represented, along with her sisters Emily and Anne, the final flowering of the literature of the Romantic Rebellion. Seldom has one little woman embodied so much British history and so much individual achievement in one, very brief life.

And Charlotte Brontë was a little woman. In physical stature, that is. According to the joyner who made her coffin, she measured four feet, nine inches.

Anne Lloyd, View of Charlotte Brontë: An Independent Will, Morgan Library, 2016

The first object to greet visitors to the Morgan exhibit is one of Charlotte Brontë's dresses, the so-called "Thackeray dress". Brontë is reputed to have worn this dress to an ill-fated dinner party at the home of William Makepeace Thackeray on June 12, 1850. She almost certainly did not wear the dress to dinner. But the story illustrates the "outsider" position of Brontë - and her sisters - in the British literary scene of the 1840's and 1850's.

The Brontë dress on view at the Morgan is of a type known as delaine dress. The word "delaine" originally referred to woolen dresses. By 1850, the term was used for light-weight dresses made of various printed fabrics, including wool-cotton mix as in the case of this dress.

Anne Lloyd, Photo of Charlotte Brontë's "Thackeray Dress", 2016

Thackeray's thirteen-year old daughter, Anne, left a vivid account of the dinner party. She described Charlotte Brontë as "a tiny delicate, serious little lady, pale with fair straight hair, and steady eyes. She may be a little over thirty; she is dressed in a little barège dress, with a pattern of faint green moss."

According to Houghton, barège was a mix of woolen and silk threads, very much in fashion for evening dresses in 1850. When it came to fabrics, Charlotte Brontë clearly knew her "stuff."

Anne Lloyd, Detail of Charlotte Brontë's "Thackeray Dress", 2016

To focus upon the "Thackeray" dress may seem obsessive, when the Morgan exhibit is bursting with "once-in-a-lifetime" treasures, including the manuscript of Jane Eyre. Yet, it is worth considering this dress along with a famous quote by Brontë who was responding to critics of Jane Eyre.

"To you I am neither Man nor Woman - I come before you as an Author only - it is the sole standard by which you have a right to judge me - the sole ground on which I accept your judgement."

Brontë published Jane Eyre under the nom de plume, Currer Bell. When she and her sisters, Emily and Anne decided to "earn their fortune" as professional writers they chose enigmatic male names, Currer, Ellis and Acton, respectively. The surname "Bell" was, perhaps coincidentally, the middle name of their father's assistant curate and Charlotte's eventual husband, Arthur Bell Nicholls.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2016) of The Brontë Sisters (c.1834) by Patrick Branwell Brontë

The Brontë sisters tried every form of employment deemed suitable for gentlewomen to earn their bread. Governessing, managing a school of their own, all that was now at an end. Their hearts were not in it and their brother Branwell's erratic behavior forbade housing students even if they could find any.

A legacy left to the sisters by their Aunt Branwell allowed them some financial freedom, but it wasn't a complete answer. In the autumn 1845, during this time of uncertainty , Charlotte Bronte came across her sister's Emily's poems. They electrified her. Charlotte faced down Emily's fury and insisted that the poems must be put before the public. The rest is history.

Charlotte Brontë, aka Currer Bell, had the right to insist upon being judged "as an Author only." Though politically conservative, Charlotte Brontë was in the vanguard of the eminent Victorian women who would stubbornly smash the barriers of the "Old Boy" British establishment.

Anne Lloyd, Photo of Charlotte Brontë's portable writing desk, 2016

The "Thackeray" dress, Charlotte Brontë's portable writing desk, the Richmond's portrait and the manuscript of Jane Eyre testify to the front-row place which Charlotte Brontë earned for herself among the "greats" of English literature. But these objects from Brontë's later life can only be understood in terms of the wondrous "little books" and poems which she and her siblings created as children.

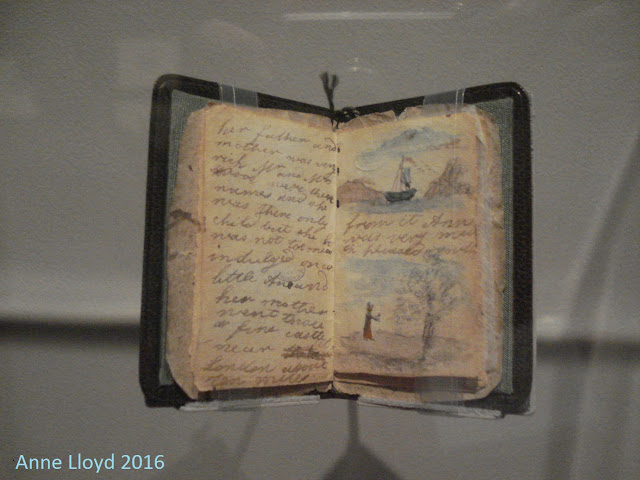

On display at the Morgan exhibit is a miniature manuscript book with water color drawings. It is dated to 1828, when the nine-year old Charlotte created this tiny treasure for her younger sister, Anne, later the author of The Tenant of Wildfell Hall.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2016) of Miniature Booklet (c.1828) by Charlotte Brontë

There once was a little girl and her name was Ane” reads the opening line of Charlotte Brontë’s first tale, complete with misspelling. Looking at this incredible work of love, one is struck by the unshakable thought that here is “genius" or at least the seed of genius.

The Brontë treasures, currently on view in the gallery of the Morgan Library, certainly testify to one of the great sagas of creativity in human history. Why else would we continue to read Jane Eyre, Wuthering Heights, Villette and The Tenant of Wildfell Hall? Why else would we throng to an exhibition such as Charlotte Brontë: An Independent Will at the Morgan Library?

Anne Lloyd, View of the Brontë's Parsonage Museum, Haworth, U.K., 2014

The truth is that our hearts, our souls, our imaginations are still moved and shall ever be moved by the greatest Brontë epic of all - the lives of the Brontë family of Haworth.

***

Text: Copyright of Ed Voves, all rights reserved

Images courtesy of Anne Lloyd and the Morgan Library and Museum, New York City

Introductory Image: Anne Lloyd, Photo (2016) Detail of The Brontë Sisters (c.1834) by Patrick Branwell Brontë, Primary Collection of the National Portrait Gallery, London.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2016) Detail of the Richmond Portrait (Charlotte Brontë) (1850) by George Richmond, National Portrait Gallery Collection, London.

Anne Lloyd, Gallery view of Charlotte Brontë: An Independent Will (the "Thackeray dress") at the Morgan Library and Museum, New York City, digital photograph, 2016

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2016) The "Thackeray dress," two-piece printed delaine dress (of cotton and wool), ca. 1850, worn by Charlotte Brontë, Brontë Parsonage Museum

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2016) Detail of the "Thackeray dress," c. 1850, worn by Charlotte Brontë, Brontë Parsonage Museum

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2016) Charlotte Brontë’s portable writing desk, with contents including pen nibs, ink bottle, and other tools, Parsonage Museum

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2016) Miniature manuscript booklet with watercolor drawings, by Charlotte Brontë, c.1828, Brontë Parsonage Museum

Anne Lloyd, View of the Brontë Parsonage Museum, Haworth, U.K., digital photograph, 2014