Time and Cosmos in Greco-Roman Antiquity

Institute for the Study of the Ancient World, New York City

October 19, 2016 - April 23, 2017

Reviewed by Ed Voves

The exhibit space of the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World (ISAW) in New York City consists of two moderately-sized galleries. The ISAW is located a couple blocks from the Metropolitan Museum of Art at 15 East 84th Street. What ought to be a classic illustration of a sapling wilting under the shadow of a mighty oak tree is not true at all.

The ISAW is a research and graduate education institute of New York University. It mounts two important exhibitions each year and somehow manages to encompass whole civilizations or historical epochs in the confines of these two galleries.

In its latest exhibit, Time and the Cosmos in Greco-Roman Antiquity, ISAW has brought together an astonishing range of art works from museums throughout Europe and the United States. ISAW has no permanent collection of its own, but knows how to pick the best of the best.

I was especially impressed that a silver figurine from the treasure of Mâcon was loaned to ISAW from the British Museum. This is the Statuette of Tutela with Planetary Divinities, the introductory image of this review.

In 1764, a vast hoard of ancient silver and gold, mostly coins, was discovered in Mâcon in France. All but eight figurines and one silver plate were melted down for the face value of the bullion. The British Museum was able to purchase the exquisite Statuette of Tutela and seven others before they were consigned to the smelting furnace.

As the name of the ISAW exhibit proclaims, the over-arching theme of the present exhibition is the biggest one imaginable: time.

Time is the absolute component of life: of our daily lives, of the march of history and ultimately of the nature of the universe. Everyone and everything exists in time.

Time's importance should occasion no surprise. But people throughout history have not been able to agree about time anymore than tribal or national boundaries.

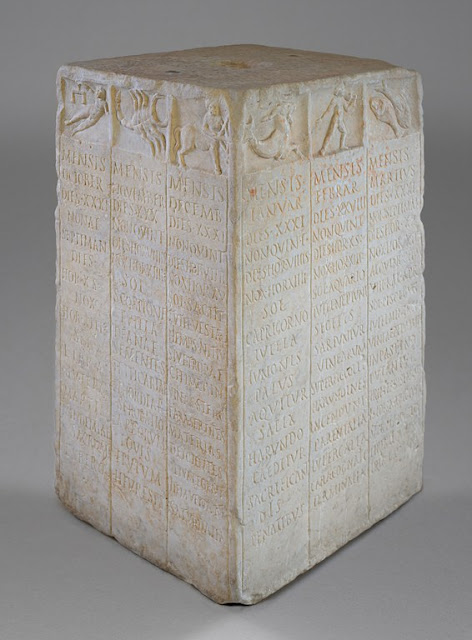

Roman Calendar Inscription with Zodiac, 1st century A.D.

Most city states in ancient times had civic and religious calendars and dating systems unique to themselves. For ancient Romans, time and history began with the founding of the city by Romulus (738 B.C. to us). The first Roman calendar was composed of only ten months and was a thorough mess. February was later added as the last month of the year, but was then squeezed to fit between January and March.

It took Julius Caesar to straighten things out in 46 B.C. Caesar introduced a proper twelve month calendar, which unfortunately for him included the Ides of March.

With just two galleries at their disposal, the ISAW curators wisely limited the exhibition to Greek and Roman civilization. But they do acknowledge the influence of ancient Egypt and the Babylonians, especially the latter on the rise of astrology which retained a powerful influence throughout ancient times. The ISAW exhibit brilliantly reveals a Classical world that was considerably less "classic" than we have been led to believe.

Roman Frieze showing Putti with Sundial, 140–160 A.D

The Greeks and Romans measured the course of the day using sundials, as is well known. However, one of the wonderfully strange objects on view in the ISAW exhibit is a small portable sun dial shaped like a ham! Historians surmise that the shape (like a Prosciutto ham) had an "eat, drink and be merry" connotation. It actually functioned, though the Greeks and Romans also used portable sundials that look like official time pieces by our standards.

Portable Universal Sundial, 1st–4th century A.D.

Many of the other works of art and artifacts displayed in Time and Cosmos seem alien to the image we have long held of the Greeks and Romans as founders of Western Civilization. And even some of the exhibit pieces that do conform to the conventional view of the Classical Age raise questions.

The superb mosaic from the Villa of Titus Siminius Stephanus in Pompeii likely depicts Plato's Academy with the sitting figure directly under the tree being Plato himself. Or it might depict the "seven sages." These pioneering thinkers included Thales of Miletus, the first "scientist" whose many accomplishments included predicting the solar eclipse of 585 B.C.Thales believed in the unity of nature whose phenomena could be explained without reliance on mythology.

Roman Mosaic Depicting the Seven Sages ("Plato's Academy"), from Pompeii

The ancient Greeks and Romans generally ignored the writings of Thales with his emphasis on scientific method. Astrology retained a strong grip on the minds of ancient people until the triumph of Christianity in the fourth century A.D. (and behind closed doors after that). The surviving art and artifacts from antiquity testify to the ceaseless efforts by people, great and small, to comprehend what was in store them, to prepare for and - if possible - to deflect "the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune."

The ISAW has an intriguing stone object on display, a fragment of what is called a "parapegma." The museum text calls it a "precursor to the modern day almanac." On it were inscribed market days in a nine-day cycle and a peg could be inserted in notch holes to keep track. This prosaic use in turn was related to astronomical, meteorological and astrological lore attached to each of these days.

Roman Parapegma, after 8 B.C.

It is easy enough to understand the day-to-day use of the parapegma, but what purpose was served by the beautifully carved "Altar" with Zodiacal Frieze and Heads of the Twelve Gods is hard to ascertain. It was mounted on a pedestal and may have been purely decorative. But we have no idea what - if anything - was placed in its center space. Perhaps a mirror for individuals to reflect on fate or some device for divination, but this remains a mystery.

"Altar" with Zodiacal Frieze and Heads of the Twelve Gods, 117–138 A.D.

The ISAW exhibit also presents a short visual "reconstruction" of the extraordinary Antikythera Mechanism. In 1900, a Greek sponge diver found fragments of what is now considered the first mechanical computer at an ancient shipwreck site. Named for the nearby island where it was found, the Antikythera Mechanism was a box containing bronze gears permitting complex calculations. Three external dials controlled the settings.

A century later, historians of science are still trying to figure out the workings of this amazing machine. The main purpose, as outlined by the ISAW, is clear. The Antikythera Mechanism can be "understood to be dedicated to astronomical phenomena and operates as a complex mechanical 'computer' which tracks the cycles of the Solar System."

The Antikythera Mechanism dates to 70 B.C., the final flourishing of ancient Greek scientific endeavor. Many of the works of art in the ISAW exhibit date from the "high noon" of the Roman Empire, during the second century A.D.

This brings to mind Edward Gibbon's famous remark about this period in his Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, the first volume of which was published in 1776:

If a man were called to fix the period in the history of the world during which the condition of the human race was most happy and prosperous, he would, without hesitation, name that which elapsed from the death of Domitian to the accession of Commodus.

Gibbon, a leading thinker of the Age of Reason, wrote his magisterial book entirely based on the surviving literature from ancient times. Gibbon knew about the religious cults of antiquity but very little archaeological evidence about them had surfaced by the time of his writing. As a result, Gibbon could find a kinship between the 1700's Enlightenment and the age of the Good Emperors.

One of the most beautiful, but troubling, works on display in Time and Cosmos dates to Gibbon's "most happy and prosperous" era. Statuette of Nemesis with Portrait Resembling the Empress Faustina I, eighteen inches in height, comes from the Getty Museum collection. It was one of the first exhibit objects to "catch" my eye in the ISAW exhibit, but the more I read and thought about it, the more questions it raised.

Statuette of Nemesis with Portrait Resembling the Empress Faustina I, 150 A.D.

Nemesis, the goddess of divine or "moral" retribution, is usually thought of in terms of delivering "just desserts" to arrogant or law-breaking individuals. This Nemesis, however, has the facial features of Faustina, the wife of the Roman emperor, Antoninus Pius, who ruled 138 to 161 A.D.

Despite the placid countenance of Faustina/Nemesis, this statuette is one of menacing portent.The wings of Faustina/Nemesis exemplify swift justice, the wheel of destiny in her hand signifies control of present and future. The prostrate figure under the foot of the goddess is an enemy of Rome.

Antoninus Pius ruled Rome during a comparatively peaceful period of the often violent Pax Romana. His predecessor, Hadrian, however, had attempted to impose the values of Greco-Roman civilization on the Jews of Palestine by building a temple to Jupiter in Jerusalem. Bitter memories of the Roman destruction of the Temple of Jerusalem in 70 A.D. were still very much alive. In 132, the revolt of Simon bar Kokhba challenged Hadrian's heedless policy, as well as the value system we see on display in the ISAW exhibit.

Nemesis, in the form of six Roman legions, eventually crushed Simon bar Kokhba and his rebels. Is there a connection between this statuette, discovered in Egypt, and the Jewish resistance to Greco-Roman civilization? Might the prostrate man under the heel of Faustina/Nemesis symbolize Simon bar Kokhba or someone else in Rome's eastern dominions who dared to think in different terms from the ruling elite?

We are unlikely to know the answer to this question. Indeed, it is a bit unfair to reach beyond the basic framework of Time and Cosmos to raise such an issue. There is so much here to think upon and ponder. Yet, it is the mark of a great museum exhibition that it sparks provocative thoughts such as these.

Time and Cosmos is ultimately concerned with "world view" - in ancient times and for all time. Just one more month remains to see this superb exhibit but the issues it addresses so brilliantly are truly "for the ages."

***

Text: Copyright of Ed Voves, all rights reserved

Images courtesy of Institute for the Study of the Ancient World (ISAW) and the British Museum

Introductory Image: Statuette of Tutela with Planetary Divinities, from Mâcon, France, 150–220 AD. Silver with Gilding Dimensions: H. 13.9 cm; W. 6 cm; D. 4.2 cm. The British Museum. GR 1824,0424.1 © Trustees of the British Museum. Digital image courtesy of the British Museum's Open Access Policy.

Roman Calendar Inscription (Menologium Rusticum Colotianum) with Zodiac, Festivals, and Agricultural Activities, found near the Palatine, Rome. 1st century A.D. Marble.H. 66.4 cm; W. 41.3 cm; D. 38.7 cm. Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli. Inventory Number:2632 © Institute for the Study of the Ancient World / Guido Petruccioli, photographer

Frieze from a Roman Sarcophagus Representing Putti with Sundial. 140–160 A.D. H. 34.5 cm; W. 23 cm; D. 7.4 cm. Musée du Louvre, Paris. Inventory Number:MA1341. Musée du Louvre, Paris, Département des Antiquités grecques, étrusques et romaines © RMN-Grand Palais / Hervé Lewandowski / Art Resource, NY

Portable Universal Sundial. Believed to have been discovered near Bratislava, 1st–4th century A.D. Bronze. H. 6.4 cm; W. 6.1 cm; D. 2.5 cm Museum of the History of Science, Oxford. Inventory Number:51358 © Museum of the History of Science, University of Oxford

Roman Mosaic Depicting the Seven Sages ("Plato's Academy"), from the Villa of Titus Siminius Stephanus, Pompeii. 1st century BC–1st century A.D. Stone Tesserae. H. 96 cm; W. 94 cm. Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli. Inventory Number:124545 © Institute for the Study of the Ancient World / Guido Petruccioli, photographer

Roman Parapegma with Lunar Days, Market Days, and Planetary Weekdays, believed to be from Latium, Italy. After 8 B.C. Marble. H. 53.5 cm; W. 33 cm; D. 3 cm. Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli. Inventory Number:2635 © Institute for the Study of the Ancient World / Guido Petruccioli, photographer

"Altar" with Zodiacal Frieze and Heads of the Twelve Gods, from Gabii, Latium, 117–138 AD. Marble. Diameter. 83.5 cm; D. 26.5 cm. Musée du Louvre, Paris. Inventory Number: MA666 Musée du Louvre, Paris, Département des Antiquités grecques, étrusques et romaines © RMN-Grand Palais / Hervé Lewandowski / Art Resource, NY

Statuette of Nemesis with Portrait Resembling the Empress Faustina I, discovered in Egypt, 150 AD. Dolomitic Marble. H. 46.4 cm; W. 20.3 cm; D. 12.7 cm. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Villa Collection, Malibu, California. Inventory Number: 96.AA.43 Digital image courtesy of the Getty's Open Content Program.