Tell It with Pride:The 54th Massachusetts Regiment and Augustus Saint-Gaudens' Shaw Memorial

National Gallery of Art Washington D.C.,

September 15, 2013 - January 20, 2014

Reviewed by Ed Voves

Tell It with Pride, the new exhibition at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, recounts one of the pivotal moments of the American Civil War. It also documents the long, ever-evolving attempt to understand and pay homage to that tragic conflict 150 years ago, especially in terms of the African-American contribution to winning the "War for the Union."

For exactly a century, there were two vantage points to properly examine the greatest of all Civil War monuments. This is the bronze sculpture honoring the sacrificial courage of Colonel Robert Gould Shaw and the African-American soldiers of his regiment. Shaw and many of his men were killed during the heroic 1863 attack on Fort Wagner, near Charleston, South Carolina.

One could go to the intersection of Beacon and Park streets on the northern boundary of Boston Common and personally view the Memorial to Robert Gould Shaw and the Massachusetts Fifty-Fourth Regiment. This bronze relief sculpture by Augustus Saint-Gaudens is enshrined across the street from the state capitol building of Massachusetts. It marks the path of the great military parade of Colonel Shaw and the 54thMassachusetts prior to their rendezvous with destiny on the night of July 18, 1863..

The second vantage point required travel of spiritual nature. Since it was unveiled in 1897, "The Shaw" has occupied a special place in American folk memory and religious conviction - at least in the North. Without going to Boston Common, an art lover or American patriot could peer into the human heart and there find a resonance of "The Shaw."

Time and tide have not budged Saint-Gaudens' mighty sculpture from either place.

There actually was a third venue for studying Saint-Gaudens' tribute to Colonel Shaw and the gallant African-American troops of the 54th Massachusetts Volunteers. Saint-Gaudens' bronze sculpture had been cast from a plaster version and this remarkable work had then been re-tooled into a stunning, golden-hued object d'art that had won international praise and awards.

In September 1997, the National Gallery of Art created a special exhibit space for this magnificent plaster model which Saint-Gaudens had exhibited to wide acclaim in Paris in 1900. This second "Shaw", on long-term loan from the Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site in Cornish, New Hampshire, had a long, interesting - and ill-starred - history behind it. Praised at first, it had then been ignored and badly preserved. The impact of this gold-patinated plaster version had also been significantly lessoned by its eventual placement at a remote location in the New England countryside where Saint-Gaudens had maintained a short-lived art colony.

Now skillfully and beautifully restored, the plaster monument to Colonel Shaw and the 54th Massachusetts is the centerpiece of the National Gallery's insightful exhibit.

Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, 1863

Tell It with Pride recounts how Shaw, the twenty-five year-old son of a prominent New England family, accepted command of the first U.S. Government-sponsored military unit comprising African-American troops. Several local units of African-Americans had been recruited in the liberated areas of the South. But the 54th Massachusetts was a special case, as it had been raised in direct response to the Emancipation Proclamation of January 1, 1863. The great African American abolitionist, Frederick Douglass had been instrumental in pressing for the regiment's authorization. Volunteers, including two sons of Douglass, answered the call from all of the states loyal to the Union and from Canada as well.

54th Massachusetts Regiment Recruitment Poster

Sergeant Major Wilson wears the swirling, light blue stripes of his rank and perhaps it is this insignia which nurtured the quiet sense of composure and self-confidence on his handsome face. Private Townsend, on the other hand, glares apprehensively at the camera. His Enfield rifle from bayonet point to rifle butt is taller than he, a point of contrast made even more incongruous by the embroidered curtains and table cloth of the setting.

Sergeant Major John Wilson, 1863

Private James Matthew Townsend, 1863

On May 28, 1863, Colonel Shaw, Sergeant Major Wilson, Private Townsend and a thousand comrades from the 54th Volunteers marched past the Massachusetts State House in a military review that was one of the most inspired dedications to the principals of political liberty and human equality in all of American history. It is this proud moment that the Shaw Memorial commemorates.

The tragic death of Colonel Shaw and many of the men of the 54th during the assault on Fort Wagner on the night of July 18, 1863 did not diminish the significance of this demonstration of idealism. In fact, the sacrificial valor of the 54th demolished one of the principal precepts of the Southern Confederacy - that African-Americans were incapable of fighting with the same measure of courage, dedication and skill as white soldiers. That delusion fell to pieces during the attack on Fort Wagner, though many in the South - and some Northern racists, too - refused to acknowledge the obvious message of the event.

It is significant that the public spirit and sense of personal initiative that characterized the conduct of the men of the 54th Massachusetts Regiment did not stop at the attack on Fort Wagner. This spirit carried on after the Civil War into the decades-long campaign to erect a memorial to Col. Shaw and his men. It was an African-American citizen of Boston, Joshua B. Smith, who was instrumental in the effort to erect a monument to Shaw and to honor the 1863 actions of the men of the 54th "by which the title of colored men as citizen soldiers was fixed beyond recall."

Fund-raising continued for nearly two decades, but the years between 1865 and 1880 were not favorable for civic projects commemorating the heroes of the Civil War. Most people in the United States wanted to get on with their lives following the end of hostilities. Huge sums were still needed to care for maimed soldiers, North and South, and to provide for orphaned children. Furthermore, Shaw's parents were modest New England people who discouraged a grand equestrian statue of their son.

In 1881, the man and the hour arrived that would lead to the creation of "The Shaw." The man was sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens. Born in 1848, Saint-Gaudens was too young, by a couple of years, to have served in the Civil War. But like Shaw, the great conflict determined the course of his life. Many of Saint-Gaudens' greatest works would have Civil War themes, but none was greater than the Shaw Memorial.

Saint-Gaudens, immensely gifted, studied art in France and Rome after the war. Returning to the United States, he received a commission to create a statue of Admiral David Farragut, one of the first major Civil War monuments. The lifelike bronze portrait of Farragut was unveiled in New York City in 1881, making Saint-Gaudens’ reputation in the process.

Saint-Gaudens soon had more work than he could handle. But when he was approached by the committee from Boston in charge of the planned Shaw Memorial in 1882, Saint-Gaudens willingly agreed to work on the project.

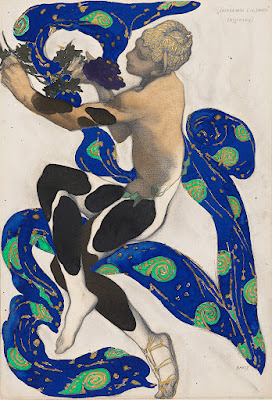

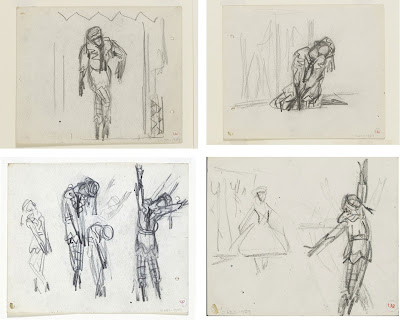

Preliminary sketch for the Shaw Memorial, 1883

Saint-Gaudens submitted several plans, initially for an equestrian figure of Colonel Shaw. But he reckoned without considering the Puritan reservations of Shaw's family. Then in 1883, Saint-Gaudens created a plaster sketch for a bas-relief showing a mounted Colonel Shaw positioned near to his men. This was accepted and a contract formally signed on February 23, 1884. The work was expected to be completed in two years, but the Boston committee had reckoned without considering the genius and ambition of Augustus Saint-Gaudens.

By the time it was unveiled on May 31, 1897, the Shaw Memorial had been transformed from a bas-relief to a statue group. Shaw and the men of the 54th do not march past in serried ranks of low-relief, blank faced heroes like the Roman legionaries on the famous ancient monument, Trajan's Column, from the second century A.D. Instead, the image of Col. Shaw is a fully realized, three-dimensional equestrian statue emerging from the setting of the action. In an absolute master-stroke, Saint-Gaudens created a similar effect for the infantrymen of the 54th. They are positioned so that the rows of troops stride forth, in step with Shaw, seemingly out of the stone architectural base that had been designed by Charles F. McKim, Saint-Gaudens' associate.

Saint-Gaudens insured that the individuality of the foot soldiers of the 54th, as well as their commander, was on view. He sculpted each head of the marching 54th infantrymen, from the grizzled old sergeant to the young, impassive drummer boy, upon separate African-American models who posed in his New York studio. In an age of racial type-casting, Saint-Gaudens affirmed human individuality to an astonishing degree.

Study Head of a Black Soldier, 1883/1893

But what these old warriors could not have known is that one of the biggest hold-ups was Saint-Gaudens' unresolved struggle on how to depict the allegorical figure, the "angel" of victory or death, who hovers over the 54th as it marches to war.

So vivid, so superbly realized are the figures of Shaw and his men that it is a cause for wonder that Saint-Gaudens bothered to include the "angel" at all, much less become obsessed with the way to properly depict her. Allegorical figures were much more the norm of nineteenth century art than today - witness the bare-breasted heroine leading the charge in Eugène Delacroix's Liberty Leading the People (1830). But the angel is a vital feature of Saint-Gaudens' work, in some ways its key component.

In an early version, the angel's face is toward the viewer. She is positioned in a pose of vigorous motion, her arm thrusting forward as if urging the viewers to join the 54th and begin the charge on Fort Wagner directly from that spot at the intersection of Beacon and Park streets in Boston.

Early Study of the Allegorical Figure for the Shaw Memorial, late 1880's

This "prototype" angel is a militant spirit much like the winged companion who accompanies General William Tecumseh Sherman in Saint-Gaudens' statue of the controversial Union General erected in New York City. Saint-Gaudens worked on the Sherman Monument for much of the time that he was involved with the Shaw Memorial. The angel who leads the grim-faced Sherman is based upon the ancient Greek personification of Victory, the Nike of Samothrace.The pairing of General Sherman and the Winged Victory brought a certain logic to Saint-Gaudens' design. Sherman's capture of Atlanta, Georgia, in the summer of 1864, and the subsequent "scorched earth" March to the Sea had, after all, produced significant Union victories.

The assault on Fort Wagner was a defeat. Despite the heroic efforts of the 54th Massachusetts and the white soldiers in the second wave of the attack, the Confederate garrison held out, safely protected by formidable "bomb-proof" bunkers.

Saint-Gaudens acknowledged the tragic nature of the sacrifice of the 54th by posing the angel's shrouded head in profile, a gaze of grieving solicitude on her face. There is no trace of the martial ardor of the Nike of Samothrace. Instead, Saint-Gaudens gave his angel the sorrowing expression of the Virgin Mary as she beholds the dead Jesus at the foot of the cross in Giotto's Arena Chapel fresco from the fourteenth century.

Allegorical Figure, Shaw Memorial, (detail) 1900

This same expression graces the face of the angel in the gilded plaster version that is the centerpiece of the Tell It with Pride exhibition. This golden-hued version, from which the bronze memorial in Boston had been cast, can be regarded as Saint-Gaudens’ "director’s cut." Saint-Gaudens had made further minor changes on the plaster version following the installation of the bronze cast in 1897.

Memorial to Robert Gould Shaw and the Massachusetts Fifty-Fourth Regiment, 1900

After being exhibited in Paris in 1900, this plaster "Shaw" began a checkered career marked by benign neglect, exposure to the New England winter and – in 1997 – brilliant restoration. Today, it serves as the "show-stopper" in this magnificent exhibition. Tell It with Pride also includes a wealth of period photos and historic artifacts including the Congressional Medal of Honor presented to Sergeant William Carney of the 54th for saving the regimental flag during the attack on Fort Wagner. This was the first ever Medal of Honor awarded to an African-American soldier of the United States.

The American Civil War took place a century and a half ago. But as you walk through the Tell It with Pride exhibition, time seems to stand still and the poignancy of the events of 1863 exerts a living presence in the museum gallery.

Shaw Memorial (detail) 1973

"Look at the monument and read the story; - see the mingling of elements which the sculptor’s genius has brought so vividly be-fore the eye. There on foot go the dark out-casts, so true to nature that one can almost hear them breathing as they march."

***

Images courtesy of the National Gallery of ArtText: Copyright of Ed Voves, all rights reserved

Introductory Image:

Augustus Saint-Gaudens

Shaw Memorial, (detail) 1900

Patinated plaster

Overall (without armature or pedestal): 368.9 x 524.5 x 86.4 cm (145 1/4 x 20 1/2 x 34 in.)

overall (with armature & pedestal): 419.1 x 524.5 x 109.2 (165 x 206 1/2 x 43 in.)

U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site,

Cornish, New Hampshire

Colonel Robert Gould Shaw

John Adams Whipple

Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, 1863

Albumen print

Overall: 10.9 x 6.1 cm (4 5/16 x 2 3/8 in.)

Image 8.4 x 5.8 cm (3 5/16 x 2 5/16 in.)

Boston Athenaeum

54th Massachusetts Regiment Recruitment Poster

J.E. Farwell and Co.

To Colored Men, 54th Regiment! Massachusetts Volunteers, of African Descent, 1863

Ink on paper

Overall: 109.9 x 75.2 cm (43 1/4 x 29 5/8 in.)

Courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society

Sergeant Major John Wilson

Unknown Photographer

Sergeant Major John Wilson

Albumen print

Image: 9.1 x 5.8 cm (3 9/16 x 2 5/16 in.)

Sheet 10 x 6 cm (3 15/16 x 2 3/8 in.)

West Virginia and Regional History Collection

West Virginia University Libraries

Private James Matthew Townsend

Unknown Photographer

Private James Matthew Townsend

Albumen print

Image: 8.6 x 5.8 cm (3 3/8 x 2 5/16 in.)

Collection of Greg French

Preliminary Sketch for Shaw Memorial, 1883

Augustus Saint-Gaudens

Preliminary Sketch for Shaw Memorial, 1883

Plaster

Overall: 41 x 38.7 cm (16 1/8 x 15 1/4 in.)

U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site,

Cornish, New Hampshire

Study Head of a Black Soldier, 1883/1893

Augustus Saint-Gaudens

Study Head of a Black Soldier, 1883/1893

Plaster

Overall: 14.8 x 13.2 cm (5 13/16 x 5 3/16 in.)

U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site,

Cornish, New Hampshire

Early Study of the Allegorical Figure of the Shaw Memorial, late 1880sAugustus Saint-Gaudens

Early Study of the Allegorical Figure of the Shaw Memorial, late 1880s

Plaster

Overall: 25.4 x 94 cm (10 x 37in.)

U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site,

Cornish, New Hampshire

Allegorical Figure, Shaw Memorial, (detail) 1900

Allegorical Figure, Shaw Memorial, (detail) 1900

Augustus Saint-Gaudens

Shaw Memorial, 1900

Patinated plaster

Overall (without armature or pedestal): 368.9 x 524.5 x 86.4 cm (145 1/4 x 20 1/2 x 34 in.)

overall (with armature & pedestal): 419.1 x 524.5 x 109.2 (165 x 206 1/2 x 43 in.)

U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site,

Cornish, New Hampshire

Memorial to Robert Gould Shaw and the Massachusetts Fifty-Fourth Regiment, 1900

Augustus Saint-Gaudens

Shaw Memorial, 1900

Patinated plaster

Overall (without armature or pedestal): 368.9 x 524.5 x 86.4 cm (145 1/4 x 20 1/2 x 34 in.)

overall (with armature & pedestal): 419.1 x 524.5 x 109.2 (165 x 206 1/2 x 43 in.)

U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site,

Cornish, New Hampshire

Shaw Memorial (detail), 1973

Richard Benson

Robert Gould Shaw Memorial, 1973

Pigmented ink jet print

Image: 30.5 x 38.7 cm (12 x 15 1/4 in.)

Sheet 32.9 x 45.6 cm (12 15/16 x 17 15/16 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington

Gift of Susan and Peter MacGill

© Richard Benson. Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York