Romantic Geography, in Search of the Sublime Landscape

By Yi-Fu Tuan

By Yi-Fu Tuan

University of Wisconsin Press/205 pages/$24.95

Reviewed by Ed Voves

"I'm sick of Portraits," declared Thomas Gainsborough in a 1769 letter to his friend, William Jackson, "and wish very much to take my viol-da gamba and walk off to some sweet village, where I can paint landskips and enjoy the fag-end of life in quietness and ease."

After finding fame and fortune painting the handsome, haughty faces of Lord So-and-So and Lady So-and-So, Gainsborough (1727-1788) yearned to escape to Nature. The refuge from the cut-throat world of London society that Gainsborough so earnestly wished for was one he never found.

Gainsborough did get to paint "landskips," lots of them in fact, vistas of England as Arcadia.

Thomas Gainsborough, Mountain Landscape with Bridge

Gainsborough, alas, never sold many of his "landskips." The artistic revolution that established the supremacy of landscape painting over portraiture did not take place within Gainsborough's lifetime. But a year after Gainsborough died in 1788, a seismic political shift occurred that opened the gates to a climate of creative endeavor we call Romanticism.

In 1789, the French Revolution began. It was a new age marked by the clash of competing values, the rhetoric of the "Rights of Man" vs the "Terror." The distinguished scholar, Dr. Yi-Fu Tuan, calls such opposites "polarized values."

Dr. Yi-fu Tuan, one of the world's great geographers, believes that the vision and sense of adventure of Romanticism are needed today. In his new book, Romantic Geography, Dr. Tuan looks beyond the narrow focus of geography in the twenty-first century, geared as it is to studying micro-environments. His aim is to rekindle the risk-taking approach that characterized the sciences - and art - during that daring, dangerous time.

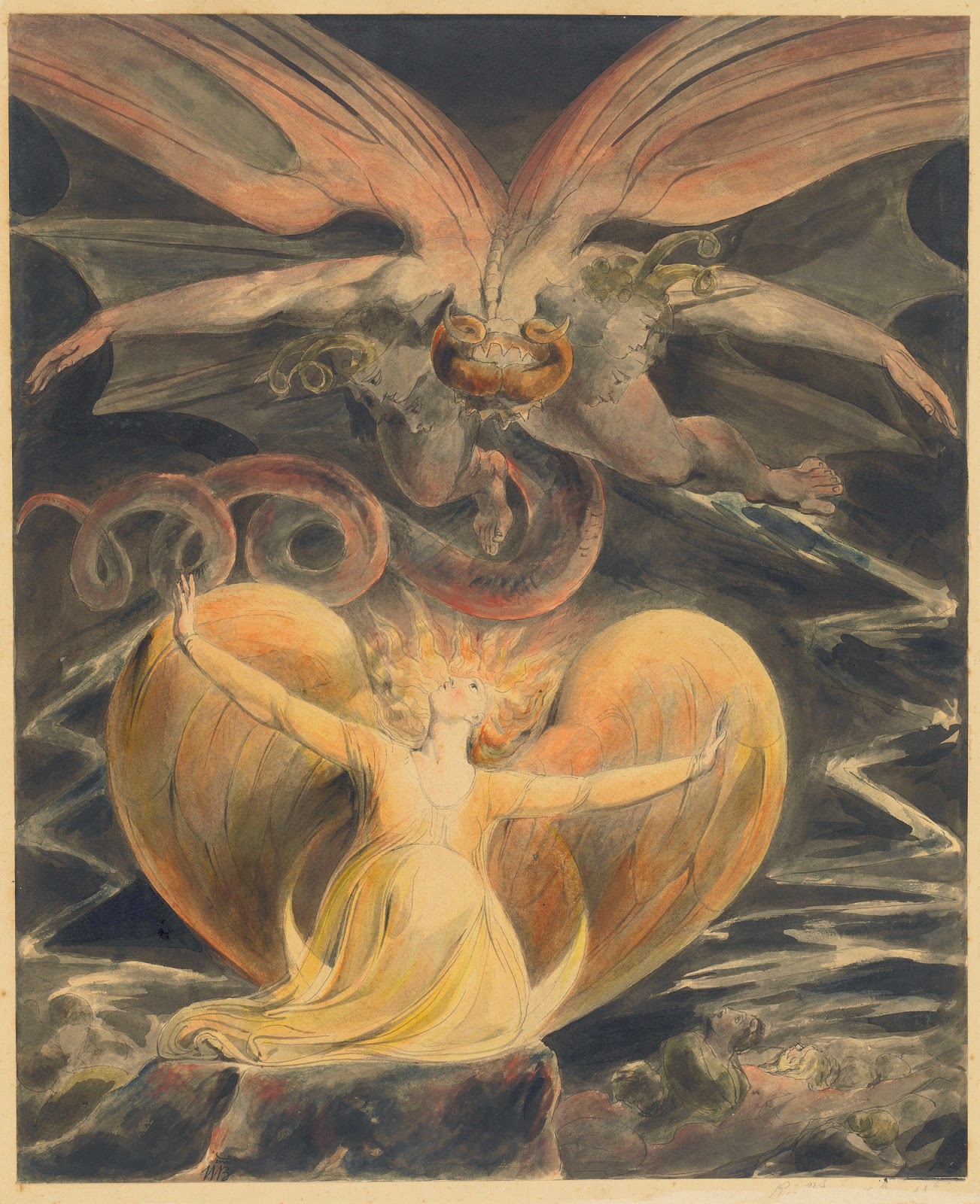

Romanticism actually began in the decade before the French Revolution and continued until the follow-up revolts throughout Europe in 1848. Although Dr. Tuan has many profound insights to offer into the period, he only mentions William Blake among the Romantic era artists. Romantic Geography, none-the-less, is a brilliant book, with much to offer to the study of landscape art.

William Blake, The Great Dragon and the Woman Clothed with the Sun

In terms of art history, Romantic Geography provides a key to understanding why Romanticism is such a vital component of human experience and why it developed in the West rather than in Asia.

Asian landscape art long predated that of Western Europe and has many impressive and inspiring attributes. Yet, landscape painting in the West, especially in the Romantic era, sparked the great revolution of Modern Art. Why did this pivotal turning point not occur in China where so many other innovations originated?

As Dr. Tuan notes, the spirit of the "quest" was well-established in Europe, dating back to the Middle Ages, indeed to Jason and Odysseus among the ancient Greeks. This daring spirit took on different guises, "good" when it came to searching for the Holy Grail or campaigns of social justice such as the abolition of slavery. Quests could also be rapacious "holy" wars like the Crusades or heedless plundering of the earth's resources.

A different mindset developed in the East. Dr. Tuan writes that in Asia, especially China, there was a deep-seated aversion to nomadic movement. Wandering Buddhist monks were honored, but the hordes of Huns and Mongols beyond the Great Wall were a different matter.

"In China, a recurrent theme in historical writing is the conflict between farmers and nomads, culture and barbarism," Dr. Tuan notes. "Chinese poetry, where it touches the steppe and desert, is filled with desolation, melancholy and death."

Western art and culture sometimes depicted wilderness regions in a negative light too. But where the Chinese sought harmony as the highest ideal, restless impulses frequently led Europeans to regard a "desert experience" as a means of strengthening one's moral fiber.

A comparison of art from the 1600's offers revealing insights about the roots of the Romantic era. Vision combined with wanderlust to propel the great revolutions, beginning in Western Europe, that have shaped our world.

In 1644, the Ming Empire of China collapsed in a dreadful conflagration of crop failure, rioting and foreign invasion. The last Ming emperor, Chongzhen, who ruled 1627-1644, was a tyrant who purged his government of capable officials and generals. He replaced them with "yes-men" whose ineptitude led to famine and military defeat. Despite Chongzhen's malign rule, most of China's educated class, steeped in Confucian ideals, maintained their loyalty. They were horrified when the emperor hung himself in the imperial garden, as Manchu invaders from the north stormed the Great Wall.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art displayed a major exhibition back in 2011, The Art of Dissent in 17th-Century China: Masterpieces of Ming Loyalist Art from the Chih Lo Lou Collection. The exhibit detailed the response through art of China's cultured elite to these disastrous events. A remnant of the nation's scholars and officials, called Ming Loyalists, tried to maintain the Ming government in southern China. When that failed, they created enduring art works preserving the culture and cosmology of the vanished Ming social order.

Zhang Feng, Landscapes

Artists like Gong Xian, Shitao, and Zhang Feng were known as yimin or "left-over" subjects. Their landscape paintings and poetry proclaimed both their pro-Ming convictions and the ideals of eternal China which would outlast any invader.

The vast geographic scope and minute human scale in these yimin works is in keeping with the traditions of Chinese art. More disturbingly, there is a total absence of people in many of these landscapes, as in the incomparable series by Gong Xian (1619-1689).

The vast geographic scope and minute human scale in these yimin works is in keeping with the traditions of Chinese art. More disturbingly, there is a total absence of people in many of these landscapes, as in the incomparable series by Gong Xian (1619-1689).

Gong Xian, Ink Landscapes with Poems

The deserted landscape is a coded message of support for the vanished Ming dynasty. It is also a fundamental revelation of the emotional state of the Ming Loyalists. The patriotism of the Ming Loyalists was courageously expressed but eventually subsumed by the wistful, elegiac nuances in their art works. These are almost devoid of the kind of determination that will spark successful wartime resistance. Like the French in 1940, the Ming Loyalists were psychologically defeated even before the Manchu invasion began.

At the very same time that Ming China was in turmoil, the kingdoms of Europe were convulsed by the Thirty Years War, 1618-1648. One of the most destructive conflicts in human history, the Thirty Years War oppressed the minds and spirits of scholars and artists in Europe as the Ming collapse did to their counterparts in China.

Chief among them was Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640), the greatest artist of his day. Rubens painted a number of passionate allegorical works extolling reconciliation and peace. When these were ignored, Rubens retired in 1635 to his estate of Het Steen in Flanders. He spent the last five years of his life, the "fag end" as Gainsborough expressed it, painting landscapes.

Ruben's landscapes are some of the greatest of the seventeenth century. They are not "dreamscapes" like Gainsborough's or Zhang Feng's. Rubens evoked realism, vigor and in some cases horror, as in this hunting scene in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The noble stag is drawing the pack of hunting dogs away from the deer in the foreground. But the stag will surely be set-upon by the dogs and savagely hacked to pieces.

Peter Paul Rubens, A Forest at Dawn with a Deer Hunt

The heightened emotionalism of Rubens' picture is the key to the Romantic art that followed nearly two centuries later. At its highest pitch - the Sublime - Romantic art reveled in horror, in depictions of violence, moody evocations of ominous or fateful events. And underpinning the sense of dread called forth by the Sublime was the hope that a New Age - a better one - would arise from the wreckage of the old.

Dr. Tuan reflects that Romanticism "inclines toward extremes in feeling, imagining and thinking." This super-charged atmosphere generates what Dr. Tuan refers to as dissonance. In this "trial by error" process, human beings struggle toward transcendence by courting possible disaster in the quest for new insights and innovations.

One of the classic paintings of the Romantic era is a perfect illustration of dissonance in action. The human future is here gripped in the begrimed, calloused hands of the stevedores or keelmen in J.M.W. Turner's Keelmen Heaving in Coals by Moonlight.

J.M.W. Turner, Keelmen Heaving in Coals by Moonlight

This 1835 painting documents the backbreaking process of loading coal from the mines of England's Tyneside region onto square-rigged sailing ships that will take it to the factories of Manchester or London. The dissonance – the drudgery and danger - of the keelmen's lives created the means for rapid change and rising standards of living that were a feature of the Industrial Revolution.

Another Romantic-era landscape, George Innes' Lackawanna Valley, picks up this theme.

In 1856, George Inness was commissioned to paint a view of the new depot of the Delaware, Lackawanna, and Western Railroad, in Scranton, Pennsylvania. By contract, Inness was tasked with giving a central place to the "roundhouse," the circular building where locomotives, passenger and freight cars were serviced for their next run. The roundhouse was not even completed as Inness set to work depicting the railroad yard and surrounding valley.

Inness’ painting was initially known as The First Roundhouse of the D. L. and W. R. R. at Scranton. The owners of the D. L. and W. R. R., however, were less than pleased. After a discrete interval, they sold the painting which eventually found its way into the collection of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

George Inness, The Lackwanna Valley

It does not take long to figure out what rattled the composure of the D. L. and W. R. R. bosses. When examining Inness’ painting, what strikes the eye – and holds it – is the field of tree stumps. The rail barons wanted the looker to focus on their big, impressive roundhouse or the puffing locomotive. That might be what the reclining figure in the foreground is looking at, but what we see are the missing trees, hewn down to build the Scranton rail depot.

Americans who first viewed Inness’ painting likely saw the missing trees too. Even amid the railroad mania of the mid-nineteenth century, alarm was beginning to mount regarding the effect on the natural environment of the rapid industrialization of the United States.

Inness could have side-stepped the issue and pleased the railroad owners by not including the tree stumps. Artists, however, must be people of integrity and Inness remained true to his vision.

Inness also remained true to the spirit of the Sublime. The full impact of his uncompromising depiction of The Lackawanna Valley can be appreciated by comparison with a photograph of the Scranton rail yard taken about a half-century later. The tree stumps are gone but so is the rest of Nature!

Americans who first viewed Inness’ painting likely saw the missing trees too. Even amid the railroad mania of the mid-nineteenth century, alarm was beginning to mount regarding the effect on the natural environment of the rapid industrialization of the United States.

Inness could have side-stepped the issue and pleased the railroad owners by not including the tree stumps. Artists, however, must be people of integrity and Inness remained true to his vision.

Inness also remained true to the spirit of the Sublime. The full impact of his uncompromising depiction of The Lackawanna Valley can be appreciated by comparison with a photograph of the Scranton rail yard taken about a half-century later. The tree stumps are gone but so is the rest of Nature!

Delaware, Lackawanna, and Western Railroad yards, Scranton, PA, c.1900

The Romantic Age thus left a mixed legacy to the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

How we respond to this ecological crisis will determine our future. Dr. Tuan recognizes the importance of stewardship of the earth. But he calls for bold, Romantic-style initiative, not the reclusive scholarship of the Ming Loyalists.

"Humans cannot just want to chew the cud on fertile land and live contentedly," Dr. Tuan writes. "They are, after all, children of God, not cattle."

***

Text: Copyright of Ed Voves, all rights reserved

Images Courtesy of the National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. , the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, the Library of Congress and the University of Wisconsin Press.

Introductory Image: Romantic Geography, in Search of the Sublime Landscape, 2014 (Cover)

Thomas Gainsborough (British, 1727 - 1788) Mountain Landscape with Bridge, c. 1783/1784 Medium: oil on canvas. Dimensions: overall: 113 x 133.4 cm (44 1/2 x 52 1/2 in.) framed: 146.7 x 167.6 cm (57 3/4 x 66 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. Andrew W. Mellon Collection. 1937.1.107

William Blake (British, 1757-1827) The Great Dragon and the Woman Clothed with the Sun, 1805 Medium: pen and ink with watercolor over graphite. Dimensions: 40.8 x 33.7cm (16 1/16 x 13 1/4 in.) support: 55.2 x 44.3 cm (21 3/4 x 17 3/8 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. Rosenwald Collection

Zhang Feng, (Chinese, active ca. 1628–1662) Landscapes, dated 1644. Medium: Album of twelve paintings; ink and color on paper. Dimensions: Each leaf: 6 1/16 x 9 in. (15.4 x 22.9 cm) Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Credit Line: Edward Elliott Family Collection, Gift of Douglas Dillon, 1987. Accession Number: 1987.408.2a–n

Gong Xian (Chinese, 1619–1689) Ink Landscapes with Poems, dated 1688. Medium: Album of sixteen paintings; ink on paper. Dimensions: 10 3/4 x 16 1/8 in. (27.3 x 41 cm) Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Credit Line: Gift of Douglas Dillon, 1981 Accession Number: 1981.4.1a–o

Peter Paul Rubens (Flemish, 1577–1640 ) A Forest at Dawn with a Deer Hunt, ca. 1635. Medium: Oil on wood. Dimensions: 24 1/4 x 35 1/2 in. (61.5 x 90.2 cm) Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Purchase, The Annenberg Foundation, Mrs. Charles Wrightsman, Michel David-Weill, The Dillon Fund, Henry J. and Drue Heinz Foundation, Lola Kramarsky, Annette de la Renta, Mr. and Mrs. Arthur Ochs Sulzberger, The Vincent Astor Foundation, and Peter J. Sharp Gifts; special funds, gifts, and other gifts and bequests, by exchange, 1990. Accession Number 1990.196

Joseph Mallord William Turner (British, 1775 - 1851) Keelmen Heaving in Coals by Moonlight, 1835. Medium: oil on canvas. Dimensions: overall: 92.3 x 122.8 cm (36 5/16 x 48 3/8 in.) framed: 127.6 x 158.1 x 14 cm (50 1/4 x 62 1/4 x 5 1/2 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. Widener Collection 1942.9.86

George Inness (American, 1825 - 1894) The Lackawanna Valley, c. 1856.

Medium: oil on canvas. Dimensions: overall: 86 x 127.5 cm (33 7/8 x 50 3/16 in.) framed: 120.3 x 161.6 x 15.2 cm (47 3/8 x 63 5/8 x 6 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. Gift of Mrs. Huttleston Rogers 1945.4.1

Delaware, Lackawanna, and Western Railroad yards, Scranton, PA. Detroit Publishing Co., publisher. Detroit Publishing, Co. Date Created/Published: between 1900-1910. Medium: 2 negatives : glass ; 8 x 10 in. Reproduction Number: LC-DIG-det-4a18925. Rights Advisory: No known restrictions on publication. Gift of State Historical Society of Colorado; 1949. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA

.jpg)