Americans in Spain, Painting and Travel, 1820-1920

Chrysler Museum of Art, Feb. 12-May 16, 2021

Milwaukee Art Museum, June 11-Oct. 3, 2021

Reviewed by Ed Voves

In the late autumn of 1869, Thomas Eakins entered into the final stages of his four years of artistic study in France. Although it had been a productive apprenticeship, Eakins felt he needed something more to set the seal of complete success on his endeavor. Eakins planned a trip to one of the other European countries where he could examine the works of "Old Masters" he had not been able to study at the Louvre.

Eakins selected a surprising destination for his farewell tour of Europe - not Italy or the Netherlands nor Austria-Hungary or Great Britain. On November 29, 1869, Eakins boarded a south-bound train for Spain.

Eakins' sojourn in Spain began a trend among aspiring American painters during the latter decades of the nineteenth century and the early twentieth. Now, an ambitious exhibition, jointly organized by Corey Piper, curator of the Chrysler Museum of Art in Norfolk, Virginia, and Brandon Ruud of the Milwaukee Art Museum, follows the footsteps of Eakins, Mary Cassatt, William Merritt Chase, Robert Henri, John Singer Sargent and Childe Hassam.

Difficulty, tinged by a certain degree of danger (mostly imaginary), imparted a sense of adventure to journeys to Spain during the 1800's. For artists like Eakins, the great traditions of Spanish painting were the primary inducement to venture south from France. The astonishing realism of Velazquez and the ethereal spirituality of Murillo exposed American painters to new dimensions in art which were often lacking in the ateliers of Paris.

Only few days after arriving in Spain, Eakins explained to his father in Philadelphia the nature of his revelatory experience in his new surroundings:

Since I am now here in Madrid I do not regret at all my coming. I have seen big painting here. When I had looked at all the paintings by all the masters I had known I could not help saying to myself all the time, its very pretty but its not all yet. It ought to be better, but now I have seen what I always thought ought to have been done and what did not seem to me impossible. O what a satisfaction it gave me to see the good Spanish work so good so strong so reasonable so free from every affectation. It stands out like nature itself.

Eakins, after studying major works by Velazquez at the Prado, quickly adapted to the influence of the Spanish Baroque master, notably his concentration on character, accentuated by dark, neutral tones in the background.

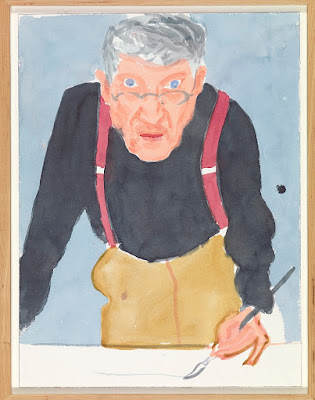

This shift in technique is readily apparent in Eakins' portrait of fellow artist, James Beckwith, on view in the exhibition. Created in 1904, this masterful work shows how the lessons of Velazquez had been integrated into Eakin's methodology, shaping, yet not determining, his own mature style.

What Eakin's achieved, his fellow-countrymen aimed to rival. Yet, it was not artists alone who ventured to Spain from the United States. Americans of diverse backgrounds traveled to Spain intent on savoring that nation's reputation for romance, for social customs little affected by industrialism. Spain's rugged landscape was dotted by castles and, yes, windmills. Spanish towns and cities, especially Toledo and Seville, retained much of their medieval character into the twentieth century

These picturesque aspects of nineteenth century Spain came at a price - paid by the Spanish people. The staggering cost in human lives during the heroic war against the Napoleonic invasion, 1808-1814 was followed by a political betrayal of the very people of Spain who had resisted the French. Goya's unforgettable paintings and prints record this tragic conflict as no other works of art were to do of war before photography.

The continuing harshness of daily life in Spain, the social and economic malaise which lingered for decades, can be seen in the face of the Spanish peasant, originally drawn by William Merritt Chase in 1881 and then engraved by Frederick Juengling two years later.

American ideas about Spain were initially shaped by a great writer, rather than an artist. The exhibition begins with artifacts related to Washington Irving's 1826 sojourn in Spain. Irving had been wandering around Europe, searching for inspiration, when an invitation reached him from Alexander Everett, the American Minister to Spain. Irving stayed three years, during which he visited - and for a time actually lived in - the famous Moorish palace, the Alhambra. Irving's romantic re-imaging of Spanish history, Tales of the Alhambra, was a huge hit with audiences in England and the United States.

Irving was a close friend of the Scottish painter, David Wilkie (1785-1841). Overshadowed today by J.M.W.Turner and John Constable, Wilkie was very popular during his day, especially for genre depictions of daily life. He painted a charming scene of Irving, immersed in a mighty tome in the Archives of Seville, the resulting information later to appear in his biography of Christopher Columbus.

For the purpose of the present exhibition, it is important to note that Wilkie's evocations of Spain were made into lithographs, appearing in Sir David Wilkie's Sketches, Spanish and Oriental, published in 1846.

Lithographs, aimed at a mass audience, later followed by photographs as book illustrations, helped whet the appetite for paintings of Spain and all things Spanish. Also important were spectacular landscape paintings of Spain, part of the mid-nineteenth century mania for "sublime" views of the world. Gibraltar from Neutral Ground by Samuel Coleman (1832-1920) was aimed at an American audience reeling from the horror of the Civil War years.

Such works were the foundation for Eakins and those who followed him to Spain, hoping to gain experience and insights that would help launch their professional careers.

Eakins had just returned home when another intrepid Pennsylvania artist made her way to Spain. Mary Stevenson Cassatt's portraits and genre scenes of Spain are very different from her later Impressionist work. But the marks of budding genius are apparent. Cassatt's handling of lace, gold braid, pleated shirts and other details of texture almost obscure the human drama in Offering the Panal to the Bullfighter (1873). Almost, but not quite.

The panal is a honey comb dipped in a glass of water which is given to matadors before they pit their lives against their fearsome, horned, adversaries. The pro-offered drink and the fantastic regalia, however, are really secondary considerations in this remarkable painting. Cassatt has captured the human chemistry in the exchange, the machismo of the bull fighter and the coy sensuality of the young woman with brilliant effect.

Cassatt's achievement with Offering the Panel was not a matter of beginner's luck. This is confirmed by the discovery of a forgotten work which she executed during her time in Spain. Cassatt's Spanish Girl Leaning on a Window Sill recently came to light in a private collection in Madrid, thanks to a Canadian art scholar, Betsy Boone. The exhibition in Norfolk and Milwaukee marks the first time that Cassatt's Spanish Girl appears in the United States.

Cassatt captured the passion and allure of the Spanish national character. Attempts by other American artists to dress family members or models in Spanish garb failed to achieve a similar effect. One American artist who did succeed evoking the Spanish identy, with its exotic "otherness" so different from the French, was Robert Henri (1865-1929).

Henri grew up in the American West when it was still open frontier. He nurtured a deep love of Spain that surely can be explained - at least in part - by the epic grandeur of the landscape of both countries. Likewise, the proud, touchy and mercurial nature of the Spanish found a kindred spirit in Americans from the "Wild" West, including Henri's own family. Henri's farther shot and killed a rival rancher in a classic range dispute over grazing rights!

Henri, famed for his Ashcan School urban realism, never tired of Spain. He visited Spain seven times between 1900 and 1926, on several occasions, leading a large group of his students on extended visits to Madrid, where he introduced them to the riches of the Prado.

Two of greatest works of Henri's Spanish oeuvre, Blind Singers (1912) and Betalo Rubino, Dramatic Dancer (1916) are on display. They are among the "show stoppers" in an exhibition rich in masterpieces and richer still in insight.

These magnificent paintings by Henri and their counterparts by Cassatt, Chase and the other Americans in Spain succeeded because their true subject was the soul of Spain and of the Spanish people. However much these great artists approached Spanish themes in terms of stereotypes - bullfighters, flamenco dancers, humble water carriers with their burros - they ultimately found their way to depict individuals rather archetypes.

What Henri wrote about Velazquez was true of himself, of Eakins, of Cassatt and the rest.

I saw the Velazquez pictures. I was in the Gallery for hours, and then wandered the streets thinking much to the glory of Velazquez. His paintings were clear of all the tricks of the art of the Salons ... simple and direct about men rather than the incidents surrounding them. To me they were great compositions. Each head or figure seemed to tell all the tragedy or comedy possible to man.

***

Text: Copyright of Ed Voves, all rights reserved Americans in Spain exhibition images courtesy of the Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, Virginia, and the Milwaukee Art Museum.

Introductory Image: Mary Cassatt, Spanish Girl Leaning on a Window Sill, ca. 1872. Oil on camvas: 24 3/8 in. (61.9 x 38.26 cm) Collection of Manuel Piñanes García-Olías, Madrid, Spain.

Gallery view of Americans in Spain, Painting and Travel, 1820-1920 at the Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, Virginia. Photo by Ed Pollard.

Thomas Eakins (American, 1844-1917) James Carroll Beckwith, 1904. Oil on canvas: 83 3/8 x 48 1/8 inches. (211.77 x 122.24 cm) San Diego Museum of Art, gift of Mrs. Thomas Eakins, # 1937.30.

William Merritt Chase (American, 1849-1916) Spanish Peasant, 1881. Engraved by Frederick Juengling, 1883. From George Parsons Lathrop's Spanish Vistas. New York: Harper and Brothers. Wood engraving: 9 x 6 9/16 inches. (22.86 x 16.67 cm) Private Collection.

David Wilkie (Scottish, 1785-1841) Washington Irving in the Archives of Seville, 1828-29. Oil on canvas: 48 1/4 x 48 1/4 inches. (122.6 x 122.6 cm) New Walk Museum and Art Gallery, Leiscester (UK), purchased from Thomas McLean, 1890. L.F2.1890.0.0

Samuel Colman (American, 1832-1920) Gibraltar from the Neutral Ground, ca.1863-66. Oil on canvas: 26 1/8 x 36 5/16 inches. (66.4 x 92.2 cm) Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, CT. Gallery Fund, 1901.35

Mary Cassatt (American, 1844-1926) Offering the Panal to the Bullfighter,1873. Oil on canvas: 39 5/8 x 33 1/2 inches. (100.6 x 85.1 cm) Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, acquired by Sterling and Francine Clark, 1947. #1955.1