Edited by Stephen Farthing Thames & Hudson/$29.95/576 pages

Reviewed by Ed Voves

Before exulting at the increase of slightly under one and a half seconds, an additional finding of the 2017 study needs to be considered. Many of the 2017 "brief encounters" included precious time spent taking "selfies" in front of the paintings.

How much attention people devote to works of art is their own business. Heaven knows, I've breezed by many a painting or sculpture myself. But I can't help thinking that art lovers would be well-advised to devote some serious time to reading Art: the Whole Story. After reflecting on the abundant wisdom in this beautiful, modestly-priced book, they might want to slow down a bit.

Originally published by Thames and Hudson in 2010, the new edition of Art: the Whole Story shows how well it has stood the test of time.

The basic premise of Art: the Whole Story is the selection of major works of art for close study. Both as singular masterpieces and as representative examples of the epochs during which they were created, these works rate as the "best of the best." A supporting gallery of "focal points" - significant details - provide insights for appreciating each of these landmarks of visual expression.

When judiciously used to guide our perception, Art: the Whole Story is a powerful research tool and a template for stimulating awareness. The subtitle of the book, however, is cause for concern. Despite its merits, it is not "the whole story" or even the final word about the works of art it examines.

The editorial team is well aware of the dangers of a "quick fix" approach to art. Noted art scholar, Richard Cork, writes:

There are no formulae available, no surefire ways of arriving at the requisite sense of alert, probing observation. Each encounter with a particular work of art demands its own singular approach ... Those who argue that audio guides are the answer, providing instant commentaries on a select number of exhibits should think again. How can you formulate an authentic response of your own when a voice, lodged intimately in the ear, is telling you precisely what to think?

The answer to that question is provided by enhancing the power of human perception. This is one of the primary aims of Art: the Whole Story.

Let's explore a case study of how the editorial team of Art: the Whole Story helps us to formulate "an authentic response" to famous works of art.

In 1821, the British Museum purchased fragments of frescoes from the tomb of Nebamun, an official in the government of Amenhotep III (c.1390-1352 BC). Amenhotep's reign was the high point of ancient Egypt's New Kingdom. The fresco episode showing Nebamun and his tabby cat hunting in the marshes of the Nile is especially well-known and beloved.

A different, more prosaic scene was chosen for study in Art: the Whole Story. This shows the normal workday routines underway on the estate of Nebamun. At center, two chariots are being readied for use. One of the chariots is harnessed to a team of mules or onagers.

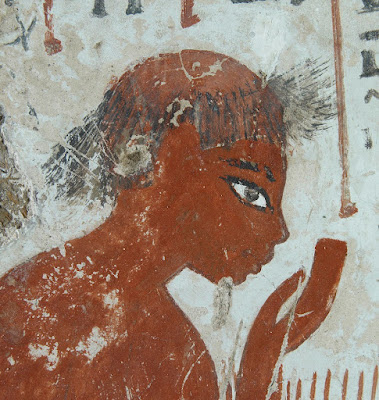

Detail of Nebamun fresco, showing elderly farm worker

The old farmer was imbued with naturalistic detail which was neither needed nor desired in the depictions of Nebamun. It was this farmer's task to maintain the necessary order and harmony on the estate for Nebamun to achieve eternal life and a semi-godlike status. At least that was how Nebamun would have interpreted the proper functioning of social life. But to us, over three thousand years later, the quiet nobility of the aged farmer is the true subject of this fresco scene.

Our perceptions of great works of art change as our consciousness expands. We can see more, appreciate more, as we look further and search deeper.

This process, of course, is at work in the lives and the oeuvres of great artists.

Christian artists were charged with creating works which directed the viewer to look inward or heavenward. As a result, the art of Christendom for many centuries rejected attempts at naturalism. Russian art, following the lead of Christian Byzantium, persisted in depicting scenes from biblical history in an ethereal manner, as can be seen in this celebrated icon, painted by Andrei Rublev in 1410.

Here, three angels visiting Abraham were depicted in a way to induce a state of meditation and prayer rather than to recreate how the event might have looked many centuries earlier.

A little over a century after Rublev's icon, Jacapo Pontormo painted a disturbing, perplexing view of the aftermath of the Crucifixion. Everything seems "wrong" about this picture when you see it displayed in an art textbook. The garish choice of colors, the off-center placement of Jesus' corpse, the dense tangle of the bodies of the mourners and disciples - appears out of "sync."

Appearances are deceiving. As the brilliant critique of the Deposition from the Cross by Ann Kay demonstrates, Pontormo's technique and perspective differed from Rublev. But both artists painted with the eye of faith.

The flamboyant pinks and blues of Pontormo's color palate were chosen so that the drama of the painting would stand out from the gloom of the church interior where it is displayed. Jesus is deliberately positioned away from the center point, thus heightening the sense of loss so graphically portrayed on the anguished faces of his mother, Mary, and his grieving followers.

Art: the Whole Story has a global reference point. Art from all points of the compass, from all cultures and epochs are included in this remarkable book. The same degree of insight and authority which the writers apply to Western artists is accorded to Asian, African and Oceanic art.

I especially appreciated the inclusion of Native American art in the shape of a Lakota Sioux "exploit" robe. This remarkable work, brought to Europe from the Great Plains of North America in the early 1800's, was featured in a great Metropolitan Museum of Art exhibition in 2015.

An excellent example of the sensitive and perceptive treatment of non-Western art appears in the section of the book devoted to Rajput or Rajasthani painting from India.

Art: the Whole Story seldom disappoints in its selection of specific works of art to analyze. I do wish that the book could have focused on at least one of the great U.S. artists who worked in America, Thomas Eakins or Winslow Homer, rather than working abroad like James McNeil Whistler. But that is a small matter, when compared with the otherwise expansive coverage and clarity of detail.

Perhaps a more controversial point is the fact that nearly a third of the book is devoted to art since 1900. Given the ever-growing complexity of modern art, the burgeoning forms of artistic media to be covered and the diversity of individual expressions, the decision to devote so much space to such a comparatively short period was understandable, indeed correct.

If some major modern artists are not accorded "star treatment" - Alberto Giacometti gets only a brief mention - others, like Paul Klee, receive their due. I was particularly impressed with the analysis of Henri Cartier-Bresson's 1932 photo of a man hopping over a puddle of water near the Gare St. Lazare train station in Paris.

Life and art intersect in Cartier-Bresson's wonderful photo. The "decisive moment," as it came to be called, occurred when the French photographer poked his Leica camera through a gap in the fence to record this incredible instant.

Thousands of years ago, the "decisive moment" occurred when the first artist dabbed mineral pigment on a cave wall. The moment came again and again as Praxiteles, Michelangelo, Vermeer, Turner, et al, followed suit.

Thanks to the wise counsel and enlightening format of Art: the Whole Story, this "decisive" moment is readily at hand.

***

Text: Copyright of Ed Voves, all rights reserved

Art: the Whole Story book cover and image of page spread , courtesy of Thames and Hudson.

Introductory Image: Johannes Vermeer, The Kitchen Maid, c. 1658. Oil on canvas: 18 x 16 inches (45.5 x 41 cm) Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. Courtesy of Rijksmuseum. https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/collection/SK-A-2344

Ustad Sahibdin (Indian, c. 1601-1700) Krishna Lifts Mount Govardhan, c. 1690. Paint on Paper: 11 x 7 7/8 inches (28.5 x 20 cm) British Museum, London. Courtesy of British Museum, Creative Commons.

Paul Klee (Swiss, 1879-1940) Fish Magic,1925. Oil and watercolor on canvas on panel: 30 3/8 × 38 3/4 inches (77.2 × 98.4 cm) Philadelphia Museum of Art # 1950-134-112 The Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection, 1950

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2018) Henri Cartier-Bresson, The Decisive Moment (Simon & Schuster, 1952), p. 39-40. Images shown are the 1932 photos, Behind the Gare St. Lazare, Place de l'Europe, Paris, France (left) and Allées du Prado, Marseille.