Assyria to Iberia at the Dawn of the Classical Age

September 22, 2014–January 4, 2015

Reviewed by Ed Voves

Assyria to Iberia at the Dawn of the Classical Age is the third in a series of landmark exhibitions exploring the birth of Western civilization. Mounted by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Assyria to Iberia traces the spread of writing, commerce, art, religion - and war - from Mesopotamia, the "land between the rivers" to distant shores as far away as Iberia, modern-day Spain.

Assyria to Iberia highlights the role of two remarkable realms. The Phoenician city-states of Tyre and Sidon, located on the coast of the Mediterranean Sea in modern-day Lebanon and Syria, are given pride of place in the exhibition. But these merchant-adventurers share the stage with the menacing Assyrian Empire that eventually conquered the Middle East from Egypt to the Persian Gulf.

The timeline of the exhibit extends from the collapse of Bronze Age civilization around 1100 B.C. to the revival of the fabled city of Babylon during the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II, 604–562 B.C.

Relief of a striding lion from Babylon

One could easily be tempted to view the story of the savvy, seafaring Phoenicians and the bloodthirsty Assyrians in terms of "good and evil." The Hebrew Bible, which began to be compiled during this period, certainly viewed the warlike Assyrians in negative terms.

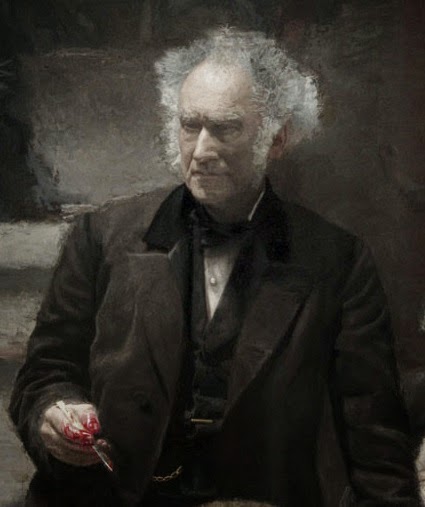

Among the first major works of art in the exhibit, a statue from the British Museum conveys the Bible's fearful estimation of the Assyrians. The image is of Ashurnasirpal II (883-859 B.C.), the king who set Assyria, then a modest state in the north of present-day Iraq, on the march of conquest. His statue, a rare example of a full-bodied sculpture rather than bas relief, projects the image of inhumanity that the Assyrians carefully cultivated. Predatory eyes, an implacable, resolute stance, hands gripping weapons of war - a sickle and a mace - these were the attributes of a model Assyrian monarch.

Statue of Ashurnasirpal II

The inscription on the king's tunic, below his battlement-shaped beard, proclaims Ashurnasirpal II as "great king, strong king, king of the universe, king of Assyria ... conqueror from the opposite bank of the Tigris as far as Mount Lebanon [and] the Great Sea, all lands from east to west at his feet he subdued."

The curators of the Met's Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art brilliantly manage to navigate a middle course between Biblical loathing and Assyrian bravado. They document events from multiple perspectives – such as the military campaign of Assyrian King Sennacherib against the Hebrew state of Judah in 694 B.C.

Lord Byron's 1815 poem, The Destruction of Sennacherib, memorably recounted the Bible's version of the event in which the Assyrian armies were thwarted by Yahweh's "Angel of Death."

The Assyrian came down like the wolf on the fold, And his cohorts were gleaming in purple and gold; And the sheen of their spears was like stars on the sea, When the blue wave rolls nightly on deep Galilee...

According to the Hebrew account, the legions of Sennacherib were decimated by plague, melting, as Byron proclaimed "like snow in the glance of the Lord." The Assyrians retreated and Jerusalem was saved.

The exhibition, however, displays another treasure from the British Museum, the Taylor Prism. This baked clay cylinder records in cuneiform script the cities of Judah that Sennacherib's troops put to the torch and the thousands of captives they seized. Hezekiah, King of Judah, is derided as being besieged in Jerusalem “like a bird in a cage.”

The Taylor Prism makes no mention of Assyrian casualties. In a strikingly similar manner to modern-day propaganda, the Assyrians always depicted themselves doing the killing - never being killed. A carved battle scene in the Metropolitan exhibit shows in gruesome detail Assyrian troops slaughtering opponents from Elam. This is a work of art that does not invite lingering contemplation.

Another Assyrian bas-relief from the British Museum, Relief Showing a Lion Hunt, is only a little less grisly. But it merits close study, for there may be a subtext in this and similar works which show Assyrian kings killing lions. In his book, The World of Art, Robert Payne wrote movingly of the contrast between Assyrian monarchs and the animals they hunted.

"A pitiless empire produced pitiless art," Payne noted, "the faces of all men are alike. Individuality is reserved for the animals which appear in the hunting scenes... "

In contrast to the impassive, formalized features of the Assyrian hunters, every effort was made to convey the uniqueness of the lions. Likewise, the sculptors highlighted the vitality and vigor with which these wild animals confronted the "civilized" men killing them for sport. Describing another hunting scene not in the Metropolitan exhibit, Payne wrote:

A wounded lioness with paralyzed hind legs tries to drag herself along by the forelegs, and every curve of the sagging back and belly, and every tendon of the forelegs suggest the awareness of death, and all the sympathy of the artist flows to the lioness.

Relief showing a lion hunt

In the lion hunting scene on view in Assyria to Iberia, the features of each dead lion in the row of feline corpses is clearly individuated. The faces of the Assyrian hunters, from king to servant lackey, are drained of humanity. Were the bas-relief sculptors, who were likely captives or hostages from conquered lands, inserting a subtle comment about the Assyrian overlords?

If so, the Assyrians missed the point. They never stopped killing until death stalked them.

In 612 B.C. a coalition of forces from Babylon, Persia and the Caucasus took advantage of a civil war among claimants to the throne of Assyria. They launched a devastating attack on Nineveh, capital of the over-stretched empire. With shocking suddenness, the "Thousand Year Reich" of the Assyrians was toppled, their trophy-laden cities sacked and set aflame. Like a mirage in the desert, the Assyrian empire vanished in the blink of an eye.

The seafaring Phoenicians lasted a lot longer and left a far richer cultural legacy. Instead of weapons of war, the chosen instruments of the Phoenicians were their navigational skills and monopoly of Tyrian red. This purple dye made from seashells was in huge demand throughout the Mediterranean basin. With this export, the Phoenicians brought in annual shiploads of silver “tribute” to bribe the Assyrians and a little left over for themselves.

The distinctive feature of Phoenician art was the fusion of elements and influences from all over the Near East, Egypt and the Mediterranean to form an "Orientalizing" style. This was favored throughout the entire region. Greece and Italy, both emerging from the "Dark Age" following the collapse of the Bronze Age palaces, are prime sites for the discovery of "Orientalizing" art. Homer's Iliad extolled the ornate metal work traded by the Phoenicians.

A silver bowl, . . . that skilled Sidonian craftsmen wrought to perfection,

Phoenician traders shipped across the misty seas.

Bowl with Egyptianizing motifs

Several of these Phoenician silver masterpieces are on display in the exhibit, including one found at Olympia, scene of the Greek Olympic Games beginning in 776 B.C. Another is this gilded silver Bowl with Egyptianizing Motifs. It was found in a 7th century B.C. grave in central Italy at Praeneste, a site associated with the Goddess of Fortune.

It was another goddess, worshiped by the Phoenicians, whose image became a dominant motif of the age - and of the Metropolitan exhibit. Ishtar or Astarte, was the goddess of love and fertility. She appeared in many guises, including the face on the exhibition's signature piece, Plaque with Striding Sphinx.

Usually shown wearing an Egyptian wig, Astarte was a beloved figure in almost all of the regions visited or colonized by the Phoenicians. These seafarers carried her image with them on their biremes, sometimes as a figurehead on these ships.

One of the most frequent poses of the goddess was in ivory carvings showing a beautiful woman peering through a window or between two columns. The Metropolitan exhibit displays a particularly exquisite example from the Louvre collection dating to the late 9th century - early 8th century B.C.

Woman at the window ivory plaque

Scholars have debated - with some academic heat - whether these "women in the window" represent goddesses, temple prostitutes or simply beautiful women. There was an element of all three in Astarte. The ancient Hebrews, who feared and reviled the seductive power of Astarte as a threat to the worship of Yahweh, would have emphasized the second interpretation. But to the Phoenician mariners, sailing in their little ships, Astarte was their protectress. And the faces on these ivory carvings would also have also reminded them of their womenfolk back home.

The Phoenicians established colonies at Carthage in North Africa and Spain. Temples to Astarte were erected at these newly-occupied sites and one, recently found near Seville in Spain, has led to a major re-appraisal of the fabled Carambolo Treasure.

Unearthed during building renovations back in 1958, the Carambolo Treasure consists of twenty-one pieces of 24-carat gold jewelry. These were initially thought to have been made by Iberian craftsman for rulers of the local Tartessos culture around 800 B.C. With the discovery of the temple to Astarte, this stunning necklace is now believed to have been part of the regalia of the high priest of Astarte's cult.

Necklace from the Carambolo Treasure

Astarte was not the only seductive woman whose dazzling face launched - or sank - a thousand ships during the age of the Phoenician mariners.

Beguiling female heads also appear on several strange, flying creatures that once decorated the rims of bronze cauldrons which blazed with fire in palaces and temples. Part bird, part human, these are the Sirens described in Homer's Odyssey, whose melodious singing lured love-sick sailors to their doom. A hanging display of several of these bronze Sirens in the Met's exhibit brings home the dangers faced by Phoenician mariners and their Greek counterparts.

Cauldron and stand

An impressive bronze cauldron, complete with its iron stand, was discovered in Cyprus, the "copper island" which was a prime trading destination of the Phoenicians. Dating to the 8th–7th century B.C., the cauldron testifies to the transition from the Bronze Age to the Age of Iron. The attached figures or protomes on the rim are male this time, Janus-headed bird men, and fearsome Griffins. The effect of viewing these extraordinary bronze visages set against leaping flames and smoke rising up from within the cauldron must have been mesmerizing.

Assyria to Iberia is a worthy successor to its predecessors, The Art of the First Cities, presented at the Metropolitan Museum in 2003, and Beyond Babylon, the 2008 exhibit which surveyed the Bronze Age. However, despite the scale of the exhibit and the jaw-dropping beauty of some of the art works on display, there is a melancholy feel to this third installment of the Met's study of the rise of civilization. There are lessons here that should have been learned a long time ago - and still haven't been.

Along with the Assyrian battle and lion-hunting reliefs, the Metropolitan exhibit presents other works of art that evoke war lust and its consequences - ancient and modern.

This statue of a scorpion bird-man is one of the Tell Halaf Sculptures that the German archeologist Baron Max von Oppenheim (1860–1946) excavated in Syria during the 1920's. This mythological character derives from the Gilgamesh epic, the sacred text of Mesopotamia and the "Fertile Crescent" lands that extended through Syria to the Hebrew kingdoms and the Phoenician port cities. Oppenheim brought this fearsome gate guardian and other sculptures from Tell Halaf to an iron foundry in Berlin which he converted into a museum.

On November 18, 1943, the British air force launched a devastating series of incendiary bombing attacks on Berlin and on November 22 the Tell Halaf Museum was set ablaze. When the cold water of the fire hoses struck the superheated basalt of the statues, the ancient sculptures literally exploded into thousands of fragments. Oppenheim rescued these shards and pieces and they were stored in a museum located in Communist East Berlin. After German re-unification, in an amazing reconstruction effort lasting nine years, many of the shattered sculptures were restored.

Statue of scorpion bird-man

From a purely artistic standpoint, the Tell Halaf rescue effort provides an up-beat conclusion to Assyria to Iberia. It certainly validates the dedication, skill and scholarship of the Metropolitan curators and their colleagues around the world. Their efforts deserve the highest praise.

Yet, it needs to be remembered that the November 22, 1943 air raid killed 2,000 Berliners, many of them women and children, as well as destroying the Tell Halaf Museum. Perhaps it was the latest news of murder and mayhem from the Middle East that oppressed my spirits upon leaving the wonderful Assyria to Iberia exhibition.

But what does it say about civilization in the twenty-first century that we can restore war-shattered statues from the age of the Assyrians and still go on killing fellow human beings with the cold, heartless demeanor of Sennacherib and Ashurnasirpal?

Text: Copyright of Ed Voves, all rights reserved

Images Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

Introductory Image:

Openwork plaque with a striding sphinx Ivory Excavated at Nimrud (ancient Kalhu), Fort Shalmaneser, Room NW 21 Neo-Assyrian period, South Syrian style, 9th–8th century B.C. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1964 (64.37.1)

Image: © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Relief of a striding lion Glazed and molded brick Babylon, Processional Way Neo-Babylonian, 604–562 B.C. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Vorderasiatisches Museum Image: bpk, Berlin/Vorderasiatisches Museum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin/

Art Resource, NY (Photograph by Olaf M. Tessmer)

Statue of Ashurnasirpal II Statue: magnesite; base: reddish stone Nimrud, Ishtar Sharrat-niphi temple Neo-Assyrian, ca. 875–860 B.C. The Trustees of the British Museum, London Image: © The Trustees of the British Museum

Relief showing a lion hunt Gypsum alabaster Nineveh, North Palace Neo-Assyrian, ca. 645–640 B.C. The Trustees of the British Museum, London Image: © The Trustees of the British Museum

Bowl with Egyptianizing motifs Gilded silver Praeneste, Colombella necropolis, Bernardini Tomb Phoenician or Orientalizing, early 7th century B.C. Museo Nazionale Etrusco di Villa Giulia, Rome Image: Bruce White

Woman at the window Ivory and gold Arslan Tash, Bâtiment aux Ivoires, room 14

Late 9th–early 8th century B.C. Musée du Louvre, Paris, Département des Antiquités Orientales Image: © RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, NY (photograph by Raphael Chipault)

Necklace from the Carambolo Treasure Gold El Carambolo (Camas, Seville)

7th century B.C.Museo Arqueológico de Sevilla; On permanent loan from the Municipal Collection of Seville Image: Bruce White

Cauldron and stand Cauldron: bronze; stand: iron Salamis, Tomb 79 Cypro-Archaic I, ca. 8th–7th century B.C. Cyprus Museum, Nicosia Image: Bruce White

Statue of scorpion bird-man Basalt Tell Halaf Citadel, Western Palace, “Scorpion Gate” Syro-Hittite, early 9th century B.C. Max Freiherr von Oppenheim-Stiftung, Cologne Image: bpk, Berlin/Vorderasiatisches Museum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin/Art Resource, NY (Photograph by Steffen Spitzner)

.jpg)