Art in Detail: 100 Masterpieces

By Susie Hodge

Thames & Hudson/$39.95/432 pages

Reviewed by Ed Voves

Art in Detail: 100 Masterpieces is an acutely perceptive survey of some of the greatest paintings and sculptures of the Western world. Written by the noted scholar, Susie Hodge, it is truly an "eye-opening" look at art.

In reviewing a wide-ranging book like Art in Detail, the first task is to find a common theme uniting all of the disparate parts. That is easy enough with Hodge's book. Every one of the one hundred works she examines, like Georges De La Tour's astonishing contrast of light and shadow, is indeed a "masterpiece."

Georges De La Tour, St Joseph the Carpenter, c. 1642

One might argue that Hodge should have selected several different choices for analysis. Leonardo da Vinci's The Virgin and Child with St. Anne would have made for intriguing study rather than another look at the relentlessly examined Mona Lisa. Yet - overwhelmingly - Art in Detail delivers what it promises: fascinating insights into one hundred of the supreme treasures of Western art.

Lurking just below the surface is another theme that is not so readily apparent. Each of these works of art was painted or sculpted by a recognizable artist. Each can be documented. We know who created it, when, where and what materials the artist used.

Beginning with Giotto in 1305 and extending to a 2014 painting by Paula Rego, Art in Detail charts the rise of artists as creative individualists. Hans Holbein's The Ambassadors (1533), with its trove of cryptic details, and Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin's Soap Bubbles, painted exactly two centuries later, treat the subject of human mortality in totally unique and absolutely dissimilar ways.

Hans Holbein The Younger, The Ambassadors, 1533

Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin, Soap Bubbles, c. 1733-34

Over the vast expanse of human history, almost all artists were anonymous creators of religious images or monuments to kings and rulers. Occasionally, a master from antiquity like Apelles achieved lasting renown but nothing of his actual oeuvre has survived. Several indisputable masterpieces like the Riace bronzes have been recovered but we do not know the identity of their creator.

That changed at the dawn of the Renaissance with Giotto and the painting of the Arena Chapel frescoes. Giotto was credited by Giorgio Vasari as having initiated 'the great art of painting as we know it today, introducing the techniques of drawing from life ..."

Hodge studies Giotto's Adoration of the Magi from the Arena Chapel frescoes, noting for instance that the Star of Bethlehem was painted to resemble Halley's Comet which had appeared in 1301.

Significantly, the resounding success of the Arena Chapel frescoes did not lead to carbon copy imitations all over Italy. Every major artist who followed Giotto - even Lorenzo Monaco whose narrative sense was much the same - always left a different "finger print" in style and technique.

Lorenzo Monaco, The Adoration of the Magi, 1420-22

This is the central paradox of Western art. The Classical tradition was relentlessly extolled by high-brow theorists. Generation after generation of students were indoctrinated to paint or sculpt like the Old Masters. Yet, nobody taught Rembrandt van Rijn to paint like Rembrandt.

No one taught Frans Hals to paint in his unique manner either. Hodge has selected Hals' The Laughing Cavalier for analysis and it is a brilliant choice. Painted in 1624, this work has many of the elements of Hals' signature style. But it also has a high degree of detail and "finish" not found in his later portraits.

Early in his career, the Flemish-born Hals used a color-drenched palette and an exacting eye for detail to impress his aristocratic patrons. We don't know the identity of the Cavalier (who really isn't laughing) but he would surely have been pleased with the embroidered lovers' knots, Mercury's staff and other motifs on his sleeves.

Frans Hals, The Laughing Cavalier, 1624

During the 1630's and 1640's, the Dutch middle-class gained social status to match their growing economic power. Hals found a ready market for portraits or character studies, the now famous tronies which American collectors have long favored.

Since many of these middle-class patrons dressed in black, Hals experimented with a bold, loose brushstroke to evoke the folds and sheen of the dark cloth. We can see an early example of this in the Cavalier's black cloak. Focusing closely on Hals' technique, Hodge provides illuminating commentary on this important detail. The following quote is characteristic of the power of perception which she devotes to all one hundred of the art works she studies:

At a time when brushstrokes were meant to be invisible, Hals made his obvious, from fine blended marks in the face to longer marks in the clothing, which create a sense of spontaneity. This freely handled application was unusual then, but in the 19th century was seen as a precursor to Realism and Impressionism.

Hodge has created a very effective technique of analyzing the details of these masterpieces. She divides each work under discussion into tightly-cropped frames. This enables her to focus on technical matters, for instance, the "wet-in-wet" method which Hals often used, "layering wet paint, rather than waiting for previous layers to dry."

This method of analysis also provides insight on thematic factors as well. The exceptional attention that Hals paid to the lace and embroidered sleeve enables Hodge to make the educated guess that the "Laughing Cavalier" was likely a cloth merchant as silk, lace and damask weaving had become major industries in Haarlem, the city in Holland where Hals worked.

Hodge's technique succeeds both for unfamiliar works or art and for paintings we've seen so often that we roll our eyes at the mention of their title. There is always something of value to discover in Art in Detail.

Jacques-Louis David,The Oath of the Horatii, 1784

Jacques-Louis David's The Oath of the Horatii, painted in 1784, has appeared in countless art history books. Kenneth Clark discussed it in the Civilization documentary series as a revolt against the status quo of Europe's Age of Enlightenment. Clark likened The Oath of the Horatii to Picasso's Guernica (which Hodge also discusses), calling it "the supreme picture of revolutionary action..."

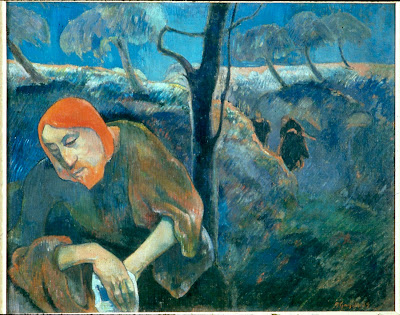

The Oath of the Horatii is also the "supreme picture" of Neoclassical art. As such it can be readily contrasted with the "supreme picture" of Romanticism, Goya's The Third of May, 1808, which also is studied in Hodge's book. But I was very stuck by a lesser known Romantic painting, which movingly demolishes all the male vanity and "call of duty" propaganda evoked by The Oath of the Horatii.

Eugéne Delacroix's Entry of the Crusaders Into Constantinople depicts a harrowing moment in one of the most disgraceful episodes of Western history. Crusading knights marching (ostensibly) to liberate Jerusalem from the Saracens in 1204 conspired with the Venetians to attack and despoil the Christian city of Constantinople instead.

Eugéne Delacroix, Entry of the Crusaders Into Constantinople,1840

The treachery of this incident needs no further comment here. But it is worth noting that Delacroix painted this compelling work of art while memories of the horror of the Napoleonic Wars still lingered in the European mind. These bloody, ruinous wars were founded upon the heartless sentiments of David's The Oath of the Horatii.

Delacroix saw war a bit differently from David. In Entry of the Crusaders Into Constantinople, the outstretched arm of the old man is a plea for the right to life rather than an invocation of the cold steel of revenge and slaughter.

When viewed in this light, Delacroix's Entry of the Crusaders Into Constantinople is not a "history" painting but a testament to humanity. The same can be said, to a greater or lesser degree, for all one hundred masterpieces in Hodge's book.

Art in Detail provides more than a mass of technical detail involved in creating a painting or a sculpture. Here, in this very fine book, is a wealth of information that will draw us back for many a return visit. Here we can explore how great artists have sought to find insights into the dilemmas of human existence and the mysteries of creative expression.

Genius is in the details, as Hodge certainly shows. Yet, the scope of skill in the visual arts is far wider than mastery of technique. Ever since cave walls served as the "picture plane," artists have been searching for ways to express the greater truths of earthly life. It's a messy, often chaotic process, but one that is directly related to human self-realization.

To her credit, Hodge finds room for such visionary matters. In an engaging discussion of Helen Frankenthaler's early experimentation with Color Field painting, Hodge quotes Frankenthaler's reaction to her efforts. Standing on a ladder to survey her work, Frankenthaler declared that she was "sort of amazed and surprised and interested."

No better description could possibly be given for the electric moment when a work of art becomes a masterpiece.

***

Text: Copyright of Ed Voves, all rights reserved

Images Courtesy of Thames & Hudson

Introductory Image: Art in Detail: 100 Masterpieces, 2016 (cover) Image credit: Thames & Hudson

Georges De La Tour (French, 1593-1652) St Joseph the Carpenter, c. 1642. Oil on canvas. 137 x 102 cm (54 x 40 in.) Louvre, Paris, France © ACTIVE MUSEUM/Alamy Stock Photo),

Hans Holbein The Younger (German, 1497-1543) The Ambassadors, 1533. Oil on oak panel. 207 x 209.5 cm (81 1/2 x 82 1/2 in.) National Gallery, London, UK © Peter Barritt/Alamy Stock Photo

Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin (French, 1699-1779) Soap Bubbles, c. 1733-34. Oil on canvas. 93 x 74.5 cm (36 5/8 x 29 3/8 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, USA classicpaintings/Alamy Stock Photo

Lorenzo Monaco (Italian, c.1370-c.1425) The Adoration of the Magi, 1420-22. Tempera on panel, 115 x 183 cm (45 x 72 in.) Uffizi, Florence, Italy The Art Archive/Alamy Stock Photo

Frans Hals (Dutch, 1582-1666) The Laughing Cavalier, 1624. Oil on canvas. 83 x 67.5 cm (32 5/8 x 26 1/2 in.) Wallace Collection, London, UK © SuperStock/Alamy Stock Photo

Jacques-Louis David (French, 1748-1825) The Oath of the Horatii, 1784. Oil on canvas. 330 x 425 cm (129 7/8 x 167 3/8 in.) Louvre, Paris, France © Heritage Image Partnership Ltd/Alamy Stock Photo

Eugéne Delacroix (French, 1798-1863) Entry of the Crusaders Into Constantinople,1840. Oil on canvas. 410 x 498 cm (161 1/2 x 196 in.) Louvre, Paris, France © Heritage Image Partnership Ltd/Alamy Stock Photo