Hymn to Apollo: the Ancient World and the Ballets Russes

Institute for the Study of the Ancient World (ISAW)

March 6 – June 2, 2019

March 6 – June 2, 2019

Reviewed by Ed Voves

Great Art is timeless. When an artist steps in front of an easel to paint, begins to sculpt a lump of clay or focuses a camera, time vanishes. There is no yesterday, no tomorrow. Art is the eternal now.

What is true for the artist is true for the art lover. To enter into the spirit of a work of art is to create a special communion with reality. The title of a great masterpiece by Nicholas Poussin perfectly expresses this heightened state of being.

A dance with the music of time.

Hymn to Apollo: the Ancient World and the Ballets Russes is a case in point. This recently-opened exhibition at the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World (ISAW) brilliantly surveys the world of dance in ancient Egypt, Greece and Rome. This in turn leads to an exploration of how the culture of antiquity informed and inspired the Ballets Russes during the early twentieth century.

Millennia and centuries do not seem to matter a great deal in this astonishing exhibition. What is on display in the ISAW galleries is the spirit of the dance. During the time you spend there, you are almost certain to feel the rhythm, sense the time-collapsing exhilaration of human bodies, hearts and souls in motion.

Plaque Depicting a Satyr and a Maenad,

from the Julio-Claudian era, 27 BC-68 AD

ISAW, a research facility of New York University, is located at 18 East 84th St. in New York City. It has no art collection of its own. Yet, this is not an obstacle to mounting outstanding exhibitions and several of the ones that I have seen at ISAW rank with the best exhibits I have reviewed in Art Eyewitness.

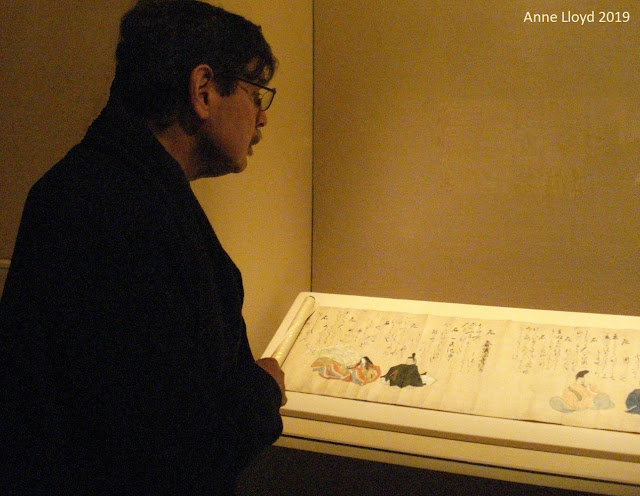

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2019) View of the entrance of ISAW, New York

To mount Hymn to Apollo, the ISAW curators called upon their colleagues at museums like the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, the Wadsworth Athenaeum in Hartford, CT. and ISAW's New York City neighbor, the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Special thanks is owed to the Harvard University Theater Collection and to the New York Public Library for Ballets Russes-related works from their respective holdings.

These borrowed works of art, ancient and modern, have been juxtaposed in such a way to inform and enlighten viewers about dance in ancient times and during the era of the Ballets Russes, 1909 to 1929. The correlation of depictions of dance on Greek and Etruscan vases with costumes for the Ballets Russes dancers is so expertly handled that the influence of ancient artifact on modern stage prop is readily apparent.

Skyphos with a Dancing Maenad, attributed to the Frignano Painter, 375–350 BC

Léon Bakst, Costume for a Nymph, from Narcisse, 1911

The mastermind of the Ballets Russes was Sergei Diaghilev (1872-1929). Diaghilev was no stranger to history and art. In 1898, he co-founded an art association in Russia, The World of Art (Mir iskusstva). The group sponsored art exhibitions and published an influential journal bearing its distinctive name. Though short-lived, the group and journal established Diaghilev as a major player in the "world" of art.

Diaghilev was both a visionary and a realist. In 1905, as he traveled around Russia collecting works of art for an exhibition, Diaghilev was shocked at the imminent sense of revolt against the government of Tsar Nicholas II. Military defeat at the hands of Japan and the ruthless repression of striking workers on January 22, 1905, "Bloody Sunday," brought Russia to the brink of destruction.

Diaghilev conceived the brilliant idea that touring companies of Russia's supremely-gifted musicians, singers and dancers could help restore his nation's battered reputation. Beginning in 1908, with a modest degree of support from the Imperial Russian government, Diaghilev achieved wonders. A year later, the Ballets Russes was officially born.

Diaghilev was determined that the theme and content of his ballets be Russian, not just showcasing Russian dancers performing in French ballets. He got his wish with immortal Russian-themed ballets like Firebird and Petrushka.

Adolf de Meyer, Lubov Tchernicheva as a Nymph with Vaslav Nijinsky as the Faun from L’Après-midi d’un Faune, 1912

How then did the culture of the ancient world, the world of Apollo, Bacchus, Cleopatra, secure an important, if not commanding, position in the repertoire of the Ballets Russes? Today, we associate roles from antiquity with Vaslav Nijinsky, the godlike superstar of the Ballets Russes. But things might have turned out very differently.

A brief survey of the history of the Ballets Russes reveals that antiquity-themed ballet constituted only a small share of the performances by that fabled company. The first year of Ballets Russes, 1909, featured Cléopâtre. The 1911 season marked the debut of Narcisse, followed the next year by L'Apres-midi d'un Faune and Daphnis et Chloé.

Léon Bakst, Costume Design for a Woman from the Village, Daphnis et Chloé

All four of these ballets featured costumes and sets by the incomparable Leon Bakst (1866-1924). But only one, L'Apres-midi d'un Faune, was choreographed by Nijinsky. Michel Fokine, who was deeply interested in ancient history, was the choreographer of Narcisse and Daphnis et Chloé.

Diaghilev's success earned him enemies at the Tsar's court and he was dismissed from the Imperial Ballet in 1911. It was an incredible blunder by an autocratic regime heedless of the gathering forces of revolution. Diaghilev, however, was determined to continue Ballets Russes programs, even without patronage.To do that, he had to expand his search for viable stories for his ballets. Necessity was the mother of his invention.

Diaghilev selected themes for his ballets from a wide-ranging body of sources to appeal to his international clientele. Thus, the staging of Narcisse, L'Apres-midi d'un Faune and Daphnis et Chloe represent a crucial stage in the globalization of the Diaghilev ballet revolution. Classical antiquity was summoned to life, as we see displayed in the ISAW galleries, to help give birth to modern music and dance.

Female “Psi Idol” Figure, from the Mycenaean, pre-Hellenic era, ca. 1250 BC

The vision of antiquity which Diaghilev, Bakst, Fokine and Nijinsky embraced was based upon recent discoveries in archaeology, such as Sir Arthur Evans' discovery of the Minoan palaces on Crete and Heinrich Schliemann's excavations at Mycenae in Greece. Europe's outstanding network of museums provided easy access to study material which Diaghilev insisted that his team examine in detail.

All the same, the ample store of knowledge about ancient dance was "circumstantial" evidence. Texts from antiquity with musical and dance notation have not survived. As a result, people in the modern age have no clue how the ancients actually danced.

The importance of dance as an integral component in religious rituals and civic ceremonies in Greece, especially, was appreciated by the beginning of the twentieth century. Diaghilev and company aimed to free modern dance from outmoded social conventions by using ancient example to liberate the modern spirit.

The Painter of London, Libation Bowl Depicting Dancing Girls

and a Girl Playing the Double Pipe, ca. 450 BC

A detailed study on ancient dance is provided in the Hymn to Apollo exhibition catalog. Space does not permit even the briefest of summary of this text. But it is vital to quote this chapter on the significance of dance in antiquity. The author, Frederick G. Naerebout, writes:

Whatever way we seek to understand the function and meaning of dance in ancient Greece, it should be clear that for the ancient Greeks themselves dance was above all an important way to make sense of the world...

Dance in antiquity was often enjoyed as a form of entertainment, but above all it was "an indispensable part of paideia, the formation of a responsible citizen."

Normally, an exhibition review like this praises the curatorial team for what is included in their displays. Hymn to Apollo presents the rare occasion when it is proper to comment favorably on the exclusion of material. In this case, it should be noted that paintings, costumes, etc. from Rite of Spring did not "make the cut" for presentation.

Rite of Spring (1913), the most famous and notorious of the Ballets Russes productions, was based on an ancient theme, though not from Greece or Rome. ISAW has certainly presented excellent exhibitions dealing with Europe during "deep" antiquity, like The Lost World of Old Europe (2010). But limiting the exhibition to the inspiration which the Ballets Russes drew from Egypt, Greece and Rome was a wise decision.

By focusing on classical antiquity, the ISAW curators insured that this important topic in the Ballets Russes story would not be marginalized. If my memory serves, Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes, the great 2013 exhibition at the National Gallery in Washington D.C., did not examine the influence of ancient dance on the Ballets Russes.

Hymn to Apollo does include an antiquity-themed ballet which was not commissioned by Diaghilev. Apollon-Musagète (Apollo,

Leader of the Muses) was composed in 1927-28 by Igor Stravinsky for the

American music patron, Mrs. Elisabeth Sprague Coolidge. Choreography was

handled by George Balanchine, then 24 years old. It was first performed in the U.S. and then in Paris by the Ballets Russes company.

Diaghilev was greatly impressed when Stravinsky played the first half of the ballet for him. He described the score as "music not of this world but from somewhere above."

Diaghilev died less than a year later, on August 19,1929. The original Ballets Russes did not survive him, though two successor companies mounted performances during the 1930's to the 1960's. By the time of his death, Diaghilev, along with Bakst, Nijinsky and Fokine, had raised ballet to become one of the most dynamic art forms of the twentieth century.

Diaghilev and company did have a little help, as this outstanding ISAW exhibition shows. They had abundant inspiration from dance and music "not of this world but from somewhere above," namely from the gods and goddesses, heroes and heroines of Egypt, Greece and Rome.

Diaghilev was greatly impressed when Stravinsky played the first half of the ballet for him. He described the score as "music not of this world but from somewhere above."

Léon Bakst, Costume Design for Tamara Karsavina as Chloé, for Daphnis et Chloé

Diaghilev died less than a year later, on August 19,1929. The original Ballets Russes did not survive him, though two successor companies mounted performances during the 1930's to the 1960's. By the time of his death, Diaghilev, along with Bakst, Nijinsky and Fokine, had raised ballet to become one of the most dynamic art forms of the twentieth century.

Diaghilev and company did have a little help, as this outstanding ISAW exhibition shows. They had abundant inspiration from dance and music "not of this world but from somewhere above," namely from the gods and goddesses, heroes and heroines of Egypt, Greece and Rome.

***

Text: Copyright of Ed Voves, all rights reserved Images courtesy of the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World (ISAW)

Introductory Image:

Artist Unknown. Statue of a Young Satyr Turning to Look at His Tail, Roman, Imperial, ca. 1–200 AD. Marble: H. 34.9 cm; W. 17.8 cm; D. 12.1 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919: 19.192.82 CC0 1.0 Image courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2019) View of the entrance of the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World, with exhibition banner for Hymn to Apollo: the Ancient World and the Ballets Russes.

Text: Copyright of Ed Voves, all rights reserved Images courtesy of the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World (ISAW)

Introductory Image:

Artist Unknown. Statue of a Young Satyr Turning to Look at His Tail, Roman, Imperial, ca. 1–200 AD. Marble: H. 34.9 cm; W. 17.8 cm; D. 12.1 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919: 19.192.82 CC0 1.0 Image courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Artist Unknown. Roman, Augustan or Julio-Claudian. Plaque

Depicting a Satyr and a Maenad, 27 BC–68 AD. Terracotta: H. 45.1 cm; W. 49.4 cm; D. 4.4 cm.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1912: 12.232.8b. CC0 1.0

Image courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Attributed to the Frignano Painter, Campania, Italy. Skyphos

with a Dancing Maenad, Late Classical, 375–350 BC. Terracotta: H. 16.5 cm; W.

15 cm. Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Gift of Dr. Harris

Kennedy, Class of 1894: 1932.56.39. Imaging

Department © President and Fellows of Harvard College

Léon Bakst (Russian, 1866-1924)

Costume for a Nymph, from Narcisse, 1911.

Dress: Silk and paint with repp detail at waist. Center-back L. 92 cm; Underarm

chest ca. 78 cm (unfitted); Waistline 74 cm. Dansmuseet—Museum Rolf de Maré

Stockholm: DM 1969/47

Image (c)

Dansmuseet – Musée Rolf de Maré Stockholm

Adolf de Meyer (French, 1868-1946) Lubov Tchernicheva as a

Nymph with Vaslav Nijinsky as the Faun from L’Après-midi d’un Faune, 1912.

Platinum print: H. 16.2 cm; W. 14 cm

New York Public Library, Jerome Robbins Dance Division,

Roger Pryor Dodge Collection: (S) *MGZEC 84-819, No. 2007 Image courtesy of the

New York Public Library

Léon Bakst (Russian, 1866-1924) Costume Design for a Woman

from the Village, for Daphnis et Chloé,

ca. 1912. Watercolor and graphite: H. 26 cm; W. 21.6 cm. The Metropolitan

Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Sallie Blumenthal, 2015: 2015.787.5. Image

source: Art Resource, NY

Artist Unknown, Mycenaean, pre-Hellenic. Female “Psi Idol”

Figure, ca. 1250 BC.

Terracotta and pigment: H. 11.1 cm; W. 6.3 cm; D. 3 cm. Brooklyn Museum, Charles Edwin Wilbour Fund:

35.744

The Painter of London, D12, Athens, Greece. Libation Bowl Depicting Dancing Girls and a

Girl Playing the Double Pipe, Classical, ca. 450 BC. Terracotta: white ground:

Diam. 22.5 cm; D. 3.2 cm. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Edwin E. Jack Fund:

65.908. Photograph © 2019 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Léon Bakst (Russian, 1866-1924) Costume Design for Tamara

Karsavina as Chloé, for Daphnis et Chloé,

ca. 1912. Graphite and tempera and/or watercolor on paper: H. 28.2 cm; W. 44.7

cm Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, CT, The Ella

Gallup Sumner and Mary Catlin Sumner Collection Fund: 1933.392 Image: Allen

Phillips/Wadsworth Atheneum