Matisse in the 1930's

Philadelphia Museum of Art

October 20, 2022 - January 29, 2023

Reviewed by Ed Voves

Original photography by Anne Lloyd

The "grizzle-chinned, wrinkle-browed" face of Henri Matisse appeared on the cover of Time Magazine on October 20, 1930. It was a notable honor in what should have been a very good year for Matisse. He had vacationed in Tahiti and traveled to the United States where he served on a prestigious art award jury. His own paintings were selling well and his son, Pierre, was setting up a gallery in New York City.

All was not well for Matisse, however, in 1930.

Matisse's critical reputation was in marked decline. Many of his fellow artists from the pioneering days of modern art looked askance at his recent paintings. Hostile art critics and the radicals of the Surrealist Movement openly scorned and derided him.

The decade of the 1930's would turn the tables on Matisse's detractors and opponents. Beginning with a commission to paint a large mural, which he boldly accepted during his visit to the United States, Matisse reinvigorated his oeuvre - and his life.

A magnificent exhibition has just opened at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, detailing this crucial decade during which Henri Matisse (1869-1954) created some of his greatest works of art. Two French museums are participating in this extraordinary effort, the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris and the Musée Matisse Nice, where the exhibition will be displayed in 2023, following its initial presentation in Philadelphia.

Approximately 140 works of art are on view in the special exhibit galleries of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, including major paintings and a selection of sculptures. Additional insight is provided by a wide-range of drawings, prints and deluxe art books for which Matisse prepared special illustrations.

The defining work of art created by Matisse during the "30's", however, could not be transported to the walls of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. But this work, a mighty mural, is close-at-hand, just a few blocks away at the Barnes Foundation. This stroke of good fortune - and savvy planning - makes for a unique opportunity to appreciate Matisse's art not likely to occur again for a long time to come.

The pivot of Matisse in the 1930's is the "back-story" of the Barnes mural, The Dance. Matisse created this sensational work of art for Dr. Albert Barnes, the most brilliant, opinionated and controversial art collector of the era. Few episodes in the history of modern art are more fascinating or influential than this improbable partnership.

Matisse in the 1930's then proceeds to examine Matisse's paintings - drenched with color and quiet passion - which followed in the wake of this celebrated masterpiece. Matisse's collaboration with the Ballet Russes de Monte Carlo rounds-off a decade of achievement which was little short of a resurrection.

Matisse during the 1930's can only be understood by first studying his works from the 1920's. Indeed, it is important to try and appreciate the cultural current of France during the years following the First World War. The dramatic "call to order" in 1918 by the French poet and filmmaker, Jean Cocteau, asserted the need for artists to reassert civilized values and traditional artistic themes after four years of insane slaughter.

Cocteau first sounded Le Rappel a l’ordre in 1918, but Matisse had already steared his own course in that direction in December 1917. Travelling to Nice, in the south of France, Matisse tried to shake-off the stress and strain of the war, both of his sons having been called to serve in the French Army. He focused his art on themes far from the unquiet Western Front.

The dominant motif in the opening gallery of Matisse in the 1930's is the odalisque. Dressed in the exotic garb of the women of Algeria and Morocco - often very scanty clothing - the odalisque was a figure of mystery and sensuality. Delacroix and Ingres had painted notable examples of this genre during the early 1800's, so when Matisse adopted the odalisque as his subject of choice, he was following in the footsteps of giants of classical French art.

Matisse loved the tactile texture of colorful fabric and the beauty of young women. Painting odalisques enabled him to indulge his enthusiasm for both.

The Moorish Screen, painted in 1921, presents an enclosed world of ease and beauty. The intricate screen, with its pattern of arabesque designs, shields the two women from even a hint of unpleasantness, noise and squalor from the outside world.

Here, in this elegantly furnished room, order has been restored. But such a relaxed atmosphere, especially given the sultry climate of North Africa, allowed repressed Europeans to engage in fantasies with overtones of sexual indulgence and exploitation.

Large Odalisque in Striped Pantaloons is a striking example of Matisse's skill in drawing and printmaking. This lithograph, created in 1925, is very much in the tradition of Ingres, one of the greatest masters of drawing in European art. On its own, individual, merits, Large Odalisque is a very impressive work, devoid of any hint of exploitation. Matisse here presents an image of a sensitive, intelligent woman at peace with her body and her personal identity.

When Large Odalisque in Striped Pantaloons is viewed along with the other depictions of nude or semi-clad women in the exhibition's opening gallery, there is a definite shift in feeling. The effect is unsettling, to say the least, putting the viewer in the role of a voyeur.

Was this true of Matisse, as well? Had the revolutionary leader of the Fauves become an artistic hedonist, content to boost his profits with sales of socially-acceptable erotica?

A very different perspective of this great French artist emerges in the pages of Hilary Spurling's brilliant biography. Matisse's painting sessions were marked by intense, often "unbearable" concentration, as the exacting painter wrestled with problems of color, design and theme.

For Matisse - and his models - there was remarkably little of Luxe, calme et volupté (Luxury, peace, and pleasure), the title of his famous 1904 painting, in the daily ordeals in his studio.

"I have always thought," Matisse wrote "that a large part of a painting's beauty derives from the artist's combat with his own limited means of expression."

Painting odalisques for Matisse was a form of expression - rigorous, challenging and artistically rewarding. Yet, it is difficult to escape the conclusion that Matisse's critics were correct to question his emphasis on painting odalisques over the course of the 1920's.

Moreover, Matisse had to be aware of the dangers of devoting himself to "classical" art.

"A young painter who cannot liberate himself from the influence of past generations," Matisse had famously declared, "is digging his own grave."

Now, the middle-aged Matisse needed a new challenge to keep from "digging his own grave."

Matisse got exactly that in the autumn of 1930. He took a day-off from his duties as an art jury member for the Carnegie Commission to visit the Barnes Foundation, located in Merion, PA, a suburb of Philadelphia.

The visit to the Barnes Foundation went well. Matisse was able to see many of his own early masterpieces. No less than twenty-five works by Matisse were part of the Barnes' collection when it opened in 1925 to a select audience.

Astutely noting the wide-range of Barnes' collecting interests, Matisse declared approvingly that "the old masters are put beside the modern ones, Rousseau next to a Primitive, and this juxtaposition helps students to understand a lot of things that the academies don't teach."

Dr. Barnes could not have expressed that better himself. He was impressed with Matisse and offered him a commission to paint a sprawling three-piece mural spanning the central hall of his private museum. Matisse agreed, the choice of topic being reserved to him rather than Barnes. This was a major concession from Barnes, but his side of the bargain was reflected in the modest $30,000 commission to be paid in three installments.

For the theme of the Barnes mural, Matisse reached back to an earlier commission. This was the creation in 1910 of two decorative panels, Dance and Music, for Sergei Shchukin (1854-1936), a Moscow industrialist with a visionary interest in modern art.

Matisse's paintings for Shchukin were huge wall-sized works. The Dance for Dr. Barnes would be vaster still, the three panels measuring fifteen feet high by forty-five feet. The central panel (slightly bigger than its companions) dwarfed the entire Russian Dance painting in size.

The epic campaign to create The Dance for the Barnes Foundation extended from the summer of 1932 to April 1933. The prolonged effort is brilliantly chronicled in the exhibition - even if the "star" of the show is off-stage at the Barnes.

An impressive array of the preparatory sketches and studies are on view, which deserve detailed study. The temptation to hurry past these "prep" works to view the huge "sketch at scale" of the central dancer's legs is hard to resist.

Equally addictive is the wonderful documentary film of Matisse at work on the mural. We see him wielding his long bamboo stick, tipped with a piece of charcoal, then carefully positioning the wheeled step-ladder, ably assisted by his faithful dog, Raudi. The film was shot by Mrs. Robert Sattler and later transferred to video.

To paint this massive work in France, rather than on site in America, invited difficulties. Matisse made a "huge mistake" in the initial measurements, according to the tactless Dr. Barnes. But he rallied quickly and carried the project through to a successful conclusion. Travelling with the completed mural to the United States in May 1932, Matisse installed The Dance in the central hall of the Barnes Foundation.

It was a moment of triumph, disappointment and the discovery of a "silver lining." Matisse's jubilation was dashed when Dr. Barnes closed the doors of his museum, soon after the mural was installed. Except for selected students and a few honored guests, hardly anyone was permitted to see The Dance. This woeful state of affairs continued for decades. Matisse fumed at Barnes, calling him "a monster of egotism."

The "silver lining" was soon discovered. Creating The Dance inspired Matisse to an extraordinary degree. The experience of painting a figurative work of this type, where the dancers represented pure movement unencumbered by any cultural or social attributes, unleashed the talents of Matisse, which had been held in check during the odalisque years of the 1920's.

The Dance was a catalyst for a sustained burst of creative genius, lasting from 1933 to 1940. For Matisse, these years were a second-lease on artistic life, a return to the vigorous use of color of the pre-World War I era, tempered and enhanced by a celebration of the human body.

The galleries devoted to Matisse's easel paintings, post-The Dance, exude a life-affirming spirit which is simply astonishing.

I sensed a real excitement and pleasure among my fellow art lovers as we beheld one "mid-Matisse" masterpiece after another: Dancer Resting,1940, from the Toledo Museum of Art and Large Reclining Nude (1935) from the Cone Collection of the Baltimore Art Museum.

And from the Philadelphia Museum of Art there was the "home team's" own Matisse icon, Women in Blue (1937).

There is a naturalness and modern-day sophistication to these 1930's paintings strikingly at odds with the 1920's odalisques. And when Matisse did hearken back to the odalisque theme, as with his 1937 Yellow Odalisque, the chic modernity of its protagonist makes the title seem like an ironic play on words.

As the decade of the 1930's progressed, Matisse continued working with unremitting energy and audacity. He collaborated on projects for ballet props and costumes, which the exhibition illustrates with a 1939 film of a dance troupe performing on a set influenced by the design of the Barnes mural.

Perhaps most significantly, Matisse returned to creating book illustrations which he had done earlier in his career. Towards the end of the 1930's, he began to focus on drawings for special edition books of a type known as livre d'artiste.

What was a sideline to his productivity during the 1930's became a vital facet of his career, following his near-death in 1941 from abdominal cancer. Matisse painted only sporadically thereafter.

Unable to stand before his easel, Matisse drew simple, yet elegant, pictures and "painted with scissors", making cut-outs. Both were used to illustrate exquisite volumes of the poems of Stéphane Mallarmé, Charles Baudelaire and the medieval poet, Charles d’Orleans.

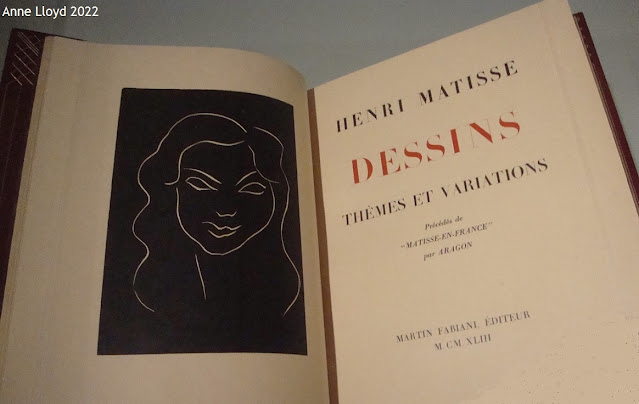

The Matisse in the 1930's exhibit ends with an examination of the 1943 book of illustrations, Drawings:Themes and Variations. This volume contains seventeen sets of drawings, each representing a letter of the the alphabet, with a total of 158 drawings. Two sets are on view in the exhibition.

In reality, this final gallery is a summation of Matisse's 1930's work and a forecast of what was to come. Working under the shadow of Nazi tyranny and the specter of his own mortality, Matisse devoted himself to a series of drawing projects which culminated in his designs for the Roman Catholic Chapel of Vence, consecrated in June 1951.

Henri Matisse died on November 3, 1954. His heart finally gave out. The stream of creative energy, rejuvenated by his acceptance of a mural commission from Dr. Albert Barnes in the autumn of 1930, was still flowing.

No comments:

Post a Comment