Lives of the Gods: Divinity in Maya Art

To compare ancient peoples, separated by thousands of miles and

hundreds of years, is always problematical. The danger of emphasizing

superficial resemblances between two cultures can easily lead to dubious or

untenable conclusions.

Despite this risk, I think that the astonishing Mayan kingdoms of southern Mexico and Central America rank with the ancient Greeks as the most dynamic cultures of their respective regions. What the Greeks were to the lands bordering the Mediterranean Sea, the Maya equaled in their influence on the Mesoamerican world.

After visiting the Lives of the Gods: Divinity in Maya Art exhibition, now in its final weeks at the Metropolitan Museum, one is struck by the singular nature of Mayan civilization. The parallels with Greece, however, are certainly interesting. The small Mayan kingdoms, like the Greek city-states, never formed a united coalition or empire. But that can be said of other native peoples of the Americas as well, like the Moche of Peru.

The fundamental influence of religion on both the Maya and the Greeks is what really counts in comparing the two cultures. As the subtitle of the Met's exhibition, Divinity in Maya Art, affirms, religion was fundamental to the Mayan peoples.

Lives of the Gods: Divinity in Maya Art is a superb exhibition, very much in the grand tradition of the Met. Inevitably, it will be compared with the 2018 Golden Kingdoms exhibit which presented 200 treasures, notably exquisite gold jewelry, of the Aztecs, Incas and Mayas. There is little glitter in the 100 works of art on view in Lives of the Gods, but visitors should not be disappointed. The Maya regarded jade as far more valuable than gold and they honored their gods with a another precious substance which cannot be put on view in a modern art museum: blood.

Mayan gods were powerful, capricious beings, willful and cruel like Zeus and company. But they were different, too. Mayan gods,

especially the youthful and much-loved Maize God, could perish and be reborn.

The gallery devoted to images of the Maize God is centered on a sensational limestone carving from Copan in Honduras. The exhibition text, expressed in almost poetical terms, deserves quotation here because it demonstrates the emotional appeal of certain aspects of Mayan religion:

The Maize God is an eternally youthful being who endures trials and overcomes the forces of death. Maya artists portrayed him as a graceful young man with glossy skin and a sloping forehead, his elongated head resembling a maize cob crowned with silky, long locks of hair... Formally appealing and conceptually rich, the Maize God’s transit through death and his subsequent rebirth were metaphors for regeneration and resilience.

Not all of Mayan cosmology touched the hearts of the people with the reassuring symbolism of the Maize God. Religion for the Maya was an awe-inspiring, often terrifying system of belief.

The terrifying aspect of statues and paintings of the Mayan gods was emulated by the kings or ajaws of Mayan states like Palenque or Tikal. This wasn't just "dress-up" on the part of Mayan rulers like the formidable King Jaguar Bird Tapir of Tonina in southern Mexico. The rulers of Mayan kingdoms assumed the personality of gods for important ceremonial and religious functions.

Due to the challenging natural environment of the Mayan world, which the Met exhibition evokes with brilliant video and sound clips, the gods of the Maya needed to be constantly placated.

The Mayas - like their northern rivals in the great city of

Teotihuacan in central Mexico, lived in danger of frequent droughts, the annual

hurricane season, periodic earthquakes and the occasional volcanic eruption.

These disasters involved the anger of deities like Chahk, the god of rain and

storms, or K’awiil, the celestial lord of lightning. These heavenly overlords lashed out when provoked by human failure

to pay them due homage.

To keep the gods pleased required rich gifts, chiefly of human blood. This sacrificial bloodletting is not pleasant to consider but it is necessary given the role it played in Mayan religion.

Blood sacrifice among the Maya came in two forms. The first involved the ritual execution of captives, an almost universal practice by the peoples of Mesoamerica. We will address this briefly later in the essay.

The other form involved shedding one's own blood, an act largely reserved for the Mayan kings, queens and nobility at moments of high importance, such as transition points on the calendar cycle or the opening of a military campaign. This act of personal mutilation was known as ch'ahb' meaning "penance" and was often inflicted by stabbing with a stingray spine.

One of the key works of art in the exhibition is a carved

limestone lintel which depicts such an act of blood sacrifice. It is entitled Lady K'abal Xook

Conjuring the Spirit of a Warrior. Lady K’abal

Xook, was the wife of Shield Jaguar III, king of Yaxchilan, located on the

border of Chiapas, southern Mexico, and Guatemala.

In this work from the British Museum collection, Lady K'abal

Xook has pieced her tongue and is bleeding into a

bowl containing pieces of cloth. These, most likely made of cotton fabric, will

absorb the blood and then be burned as an offering. Weakened by bleeding and

related rituals such as fasting, Lady K’abal Xook will be enabled to enter into

a trance state and commune with the other world.

This is exactly what is depicted in the detail above. A

spirit warrior, armed with shield and spear, emerges from a giant serpent's

mouth, in order to converse with Lady K'abal Xook.

The scene most likely refers to preparations for war, as her husband's kingdom,

Yaxchilan, was one of the most aggressive Mayan

states.

The impressive carving of Lady K'abal Xook and the spirit warrior bears a few faint traces of the vivid colors with which it was painted when created around the year 725. Whatever guidance she received in her vision ultimately failed to help Lady K'abal Xook's homeland. The population of Yaxchilan, worn-down by constant warfare and drought, abandoned the city a century later, during the widespread collapse of the Classical Mayan kingdoms.

A very different visit by a celestial being was carved into the upright back panel of a throne (above). It was discovered in Guatemala, at a site on the Usumacinta River not far from Yaxchilan. The date of its creation is unknown, but is projected as occurring between the seventh and ninth centuries. I don't profess to being an expert in Mayan art, but I suspect that this wondrous work of art (my favorite in the exhibition) was created in the earlier range of these dates.

This carved backrest to a throne shows a Mayan king (at right) conversing with a small, supernatural visitor (center). This unearthly creature has the face of a jaguar deity and wings. His upward gaze meets that of the Mayan ajaw. It is truly a meeting of two worlds.

Oddly enough, the face of the jaguar deity resembles that of a shipwrecked Spanish sailor, though centuries before Columbus. Behind him, a royal attendant takes in the interview, perhaps mystified, as we are, at what is going on.

What message does the jaguar deity impart to the intently-listening king? Of course, we cannot know. But experts in Mayan art and religion locate the scene to a cave, sacred places to the Maya. Whatever communication is being given, it is certainly of importance.

What impresses me with this magnificent carving is the tone of a style and presentation. It is free of the frightful imagery which we see on carvings from the eighth and ninth centuries when the Mayan kingdoms were in their death spiral. That is why I surmise that it should be dated earlier, before the fatal steps to the dissolution of the Classical Mayan age had been taken.

Indeed, Mayan art of the earlier periods, (proto-Classical and early Classical, third-fifth centuries) often demonstrates humane values and a sense of humor. There are quite a few examples of early Mayan art on view in Lives of the Gods, making this part of the exhibition a very enjoyable and compelling trip back in time.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) Whistling Vessel, 5th century

Displayed close to the Throne Back carving is a whistling device showing another mythical scene. Activated by being filled with water, the ceramic vessel mounts a vignette showing a trickster tale. A fearsome bird deity confronts a kneeling human being, unaware of a cat climbing-up the side of the vessel, ready to pounce.

Other ceramic masterworks on view comprise a group of lidded vessels for feast days, topped with animal knobs or handles. Howler monkeys, a peccary and a turtle with a grinning man's head emerging from its mouth attest to the Maya kinship with the animal realm and a generous helping of fun. It's hard to resist a smile when looking at these wonderful examples of Mayan pottery.

As the timeline of Lives of the Gods reaches the eighth and ninth centuries, the Mayan success story began to turn to ashes. The complex turn of event, drought, soaring population, hardening class distinctions are still being studied by historians. One thing can be certain, during the 700's, the time of Lady K’abal Xook's vision quest, warfare in the Mayan world escalated from low-intensity raids to secure a few captives for sacrifice to rampaging campaigns of wholesale destruction.

The terrible eclipse of Classical Mayan civilization is evoked in the carved images of bound prisoners awaiting execution. As part of his humiliation, a captive warrior named Yak Ahk' has been dressed as a jaguar deity, who had been tortured and killed in a tale from Mayan myth.

The precise chronology of the Maya wars is still incomplete and likely to remain so. Looking at this one carving is quite sufficient, however, to illustrate the suicide of the Classical Maya kingdoms. The image of Yak Ahk's suffering recalls the haunting 1971 photo of a young Vietnamese girl, Phan Thi Kim Phuc, set aflame by napalm. One picture tells us all we need to know.

The Mayan people proved able to survive the apocalypse of the Classical kingdoms. After the great cities were abandoned, by the year 900, Mayan life reconfigured on a localized, village basis. This decentralized community structure produced less in the way of great art, but enabled the Maya to survive the Spanish invasions of the 1500's and the epidemic diseases which followed in the footsteps of the Conquistadors.

The Met exhibit pays tribute to contemporary Maya life with a colorful video clip of a modern day festival. Dance of the Macaws in the Santa Cruz Verapaz, Guatemala, was filmed by Ricky Lopez Bruni. Dance of the Macaws exudes the life and spirit of the Maya, filling the exhibition gallery with incandescent light - and a palpable feeling of life!

The survival of the Maya over the ages and their still-flourishing folk-culture is as remarkable a phenomenon as the pyramids, statues and paintings their ancestors created over twelve hundred years ago.

Happily, Lives of the Gods: Divinity in Mayan Art will be traveling to the Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, Texas, after it closes at The Met. This year marks the 50th anniversary of the Kimbell Museum and I can't conceive of better company for this celebration than the Maya, ancient and modern.

Text: Copyright of Ed Voves, all rights reserved

Original photography, copyright of Anne Lloyd

Introductory Image: Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) Maize God, 715, from the British Museum. Details below.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) Gallery view of the Lives of the Gods: Divinity in Maya Art exhibit, showing Column, from Campeche, Mexico, c. 800-900. Limestone: H. 68 3/4 x 29 in. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

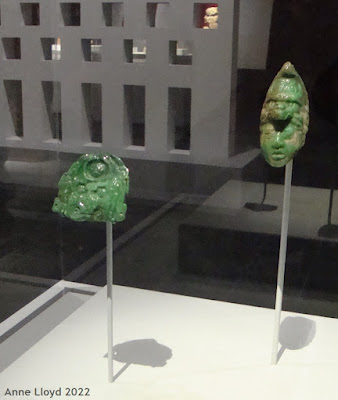

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) Gallery view of the Lives of the Gods exhibit, showing Maya jade pendants, 7th-9th century. Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022 ) Gallery view of the Lives of the Gods exhibit, showing Maize God, from Copan, Honduras, 715. Limestone: H. 35 1/16 x W. 22 1/4 in. x D. 11 13/16 in. 264.6 lbs. British Museum.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022 ) Censer Stand, from Palenque, Mexico, c. 690–720. Ceramic, traces of pigments: H. 44 × W. 22 × D. 12 1/4 in.,103 lb. (111.8 × 55.9 × 31.1 cm, 46.7 kg) Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, TX

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022 ) Jaguar God Censer Stand, from Palenque, Mexico, 7th–8th century. Ceramic: H. 26 × W. 14 9/16 × D. 6 5/16 in., 132.3 lb. (66 × 37 × 16 cm, 60 kg) Museo de Sitio de Palenque Alberto Ruz

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022 ) King Jaguar Bird Tapir, from Tonina in Chiapas, Mexico, early 7th century. Limestone: 8 ft 5 9/16 in. x 28 3/4 in. x 20 1/16 in. 881.8 lb. Museo de Sitio de Tonina, Mexico.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022 ) Gallery view of the Lives of the Gods exhibit, showing video of Tikal and El Mirador, Guatemala, filmed by Ricky Lopez Bruni.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) Lady K'abal Xook Conjuring a Supernatural Warrior, Yaxchilan, Mexico, 725. Limestone: H. 47 5/8 × W. 33 11/16 × D. 5 5/16 in., 509.3 lb. (121 × 85.5 × 13.5 cm, 231 kg) British Museum.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) Detail views of Lady K'abal Xook Conjuring a Supernatural Warrior.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) Gallery view of the Lives of the Gods exhibit, showing Throne Back, from Mexico or Guatemala, 7th-9th century. Limestone: H. 43 11/16 x W. 65 3/8 x D. 9 1/4 in. 937 lb. Museo Amparo Collection, Puebla, Mexico

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) Detail views of Throne Back (See above).

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) Whistling Vessel, from Guatemala or Mexico, 5th century. Ceramic: H. 11 7/8 x W. 7 3/4 x D. 5 1/4 in. Metropolitan Museum of Art

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) Lidded vessel with Peccary Handle, from Guatemala, 4th century. Ceramic: H. 10 5/8 x Diam. 12 5/8 inches. Museo de Nacional Arqueologia & Ethologia, Guatemala.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) Lidded Vessel with Mythological Turtle, 4th century. Ceramic: H. 9 5/8 x Diam. 10 7/16 inches. Museo de Nacional Arqueologia & Ethnologia, Guatemala. Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) Gallery view of the Lives of the Gods exhibit, showing statues of captive warriors, Yak Ahk' (left) and Muwaan Bahlam,

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2023) Yak Ahk' as Captive, Impersonating a Jaguar Deity, c. 700. Sandstone: H. 22 7/16 x W. 18 1/8 x D. 4 5/16 in. 176.4 lb. Museo de Sitio de Tonina, Mexico.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) Gallery view of the Lives of the Gods exhibit, showing video clip of Dance of the Macaws. Filmed by Ricky Lopez Bruni.