Art Eyewitness Essay

Lydia Cassatt: Model and Muse

By Ed Voves

Original Photography by Anne Lloyd

It is a mark of a great exhibition when our expectations have been met (or exceeded), some of our preconceptions have been confounded and our vision of art and awareness of life have been expanded.

Mary Cassatt at Work, on view at the Philadelphia Museum of Art until September 8, 2024, succeeds on all three counts.

In the case of expanding vision and awareness, the Cassatt exhibition focused my reflections on Cassatt's life in a way which was a considerable departure from the theme of the exhibition. I certainly had not begun to think along such a different, if not divergent, train of thought when I first visited the exhibition galleries back in May.

Entrance to the Mary Cassatt at Work exhibition

I had expected Lydia Cassatt to make her presence felt in the exhibition. She was the model for one of the premiere paintings in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA) dating to the late 1870's. Now entitled Woman in a Loge, this painting, set in one of the exclusive, mirror-backed compartments at the Paris Opera, used to be called LydIa in a Loge.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024)

Mary Cassatt's Woman in a Loge,1879

In the setting of the Impressionist gallery, Woman in a Loge, reigns like a queen on her throne.

As can be seen in the photo above, Woman in a Loge, is normally displayed in an ornate, golden frame. But that is not how the curators of Mary Cassatt at Work present the painting. Instead, we see it in an austere frame, painted in a light olive hue. Surprisingly, since the the late 1870's were the height of the "gilded age," this modest frame was the type and color which Cassatt chose for the painting back in 1879.

Mary Cassatt's Woman in a Loge, displayed as it was in 1879

Gallery view of the Mary Cassatt at Work exhibition

Lydia Cassatt was the elder sister of Mary. She was born in 1837, the year that Queen Victoria's reign began. While Mary, nicknamed "Mame", boldly launched her career in the arts, Lydia remained at home. Unmarried and untrained for any vocation outside of the family circle, Lydia seemed fated for the women's role much praised in a popular poem of the time, "the angel in the house."

In 1874, Mary made the audacious decision to settle and work in France - without financial support from her family. In a quiet act of rebellion, Lydia decided to follow in her younger sister's footsteps. In what was most likely posed as the role of chaperone, Lydia joined Mary in Paris in 1875.

The Cassatt sister's independence lasted two years. Lydia's health became a concern and their parents decided to join them.

When not sightseeing in Paris, Lydia managed their modest household, while Mary painted. Lydia also posed for "Mame" whose oeuvre remained oriented to portraits and genre studies rather than landscapes. Models cost money and the Cassatt sisters had precious little to spend with Mary's professional reputation yet to be made.

If, as seems very likely, Lydia posed for Woman in a Loge, the fidelity of the facial features of the beautiful and vivacious young woman in the painting to those of Lydia in real life needs to be addressed.

It's not an easy matter to resolve, as no portrait photos of Lydia have apparently survived.

In 1878-79, when Mary was working on Woman in a Loge, Lydia was aged 41. She was no longer a young woman by Victorian standards. Moreover, Lydia had recently been diagnosed as suffering from a serious kidney disorder known as Bright's Disease.

Is Lydia the Woman in a Loge? If so - and I believe it is her -then Woman in a Loge is an idealized portrait. It is also an "in-denial" portrait of a seriously-ill woman.

Another, very different, portrait of Lydia, dating to 1880, reveals a shocking physical decline from Woman in a Loge.

Entitled Autumn, this powerful and poignant work is in the collection of the Musee de Petit Palais, Paris. Given the personal/family relevance of Autumn, it is surprising that Mary Cassatt selected Autumn to feature among her contributions to the 1881 Impressionist salon. Yet, she did.

Autumn is not on view in Mary Cassatt at Work. But the exhibition does display numerous works depicting Lydia between 1878 and the year of her death, 1882. From these, it is clear that Mary Cassatt was grappling with a subject seldom addressed by the Impressionists in their paintings - human mortality.

Gallery view of Mary Cassatt at Work, showing paintings

"It looks like Mary Cassatt was painting her sister's passing," Anne said, and she is undoubtedly correct.

In terms of chronology, the series of depictions of Lydia begins with a small work from a private collection, Lydia Seated in the Garden with a Dog on her Lap. Painted with a bold Impressionist verve that rivals Monet, it dates to around the same time as Cassatt was working on Woman in a Loge. It is hard to conceive of two pictures of the same person being so different.

The colorful and historic setting of this painting was Marly-le-Roi, the site of a grand chateau of Louis XIV destroyed during the French Revolution. Despite the verdant background and the engaging dog on Lydia's lap, there is an ominous note to this work. Significantly, Lydia is portrayed from the back. In coming upon her from behind, we are not being shut-off from this paradise-like locale, but rather excluded from her thoughts.

In the paintings which enable us to study Lydia's face, it is once again apparent that Mary Cassatt was well aware of what was happening to her sister, physically and emotionally.

Mary Cassatt's Lydia at a Tapestry Frame, 1880-81

Mary Cassatt's Lydia Crocheting in the Garden at Marley, 1880

If you look closely at Lydia's face in these paintings, there is battle of emotions taking place in her countenance. A deep note of sadness, as her life force drains way, is countered by a stoic courage to keep-up the appearances of normalcy, to keep working no matter how mundane or trivial the task may seem. Lydia is dying and, yet, bravely struggling to live.

Another of Mary Cassatt's paintings of Lydia is on view in the exhibition. It is a very familiar and much loved work from the PMA's collection. Driving (sometimes referred to as A Woman and a Child Driving) dates to 1881. It shows a healthy, confident Lydia holding the reigns of a carriage. Edgar Degas' young niece is beside her and a groom sitting behind, ready to manage the horse and carriage when they have reached their destination.

Mary Cassatt's Driving, 1881

This is customarily viewed as a "Youth and Experience" painting. As its regular placement is in the American art galleries at the PMA, a contrast with Woman in a Loge is not the easiest. Driving is presented in a different gallery in the exhibition, but it was still fresh in my mind when I gazed at Lydia Crocheting in the Garden at Marly (1880).

Lydia Cassatt died on November 7, 1882, at the age of 45. Her passing was an excruciating ordeal, described by her father as "many years of ill-health and 84 days of deathbed agony."

Mary Cassatt was devastated by Lydia's death. She was unable to resume painting and printmaking for several months after losing her sister.

Lydia's illness and death may be interpreted in a number of ways. Death is the common lot of all humankind. Yet, Lydia's "deathbed agony" was a true example of the religious concept of redemptive suffering.

During the course of my research for this essay, I chanced upon a superb scholarly article entitled "Mary Cassatt's portraits of her sister, Lydia: Tracing signifers of disease and impending death."

The 2022 article, written by Lini Radhakrishnan of Rutgers University, closely studies Cassatt's paintings of Lydia. This article is available by open access on the Internet at the following link. It is a "must-read" for anyone interested in Mary Cassatt's life and art.

Radhakrishnan's analysis brilliantly details the close correspondence of Cassatt's depiction of the facial features, skin tone and other physical attributes of Lydia's tormented body with the actual "signifers" or manifestations of kidney disease.

Rather than try and paraphrase the clinical analysis of all the paintings Radhakrishnan surveys, I will quote a brief passage from the treatment devoted to Lydia at a Tapestry Frame.

Detail of Mary Cassatt's Lydia at a Tapestry Frame, 1880-81

Radhakrishnan writes:

As the title indicates Lydia is depicted at a tapestry frame, but this time the hands at work are neither gloved nor elegant. The left hand seen under the frame has become misshapen and the bluish gray tinge seen on the contorted digits denote poor oxygenation, a distinct sign of diminishing kidney function. There is a similar discoloration on her facial skin and signs of edema or swelling around the eyes and under the chin. Edema was a condition linked to Bright’s disease and referred to the puffiness caused by excess fluid trapped in the body’s tissues.

Lydia's travail, physical and emotional, was not in vain. Earlier I described Lydia as an exemplar of redemptive suffering. For many, the idea that one person''s acceptance of pain or privation may benefit others is a difficult concept to grasp. Yet, Lydia Cassatt's suffering would have a transforming effect on her sister's outlook on life and art

Many Cassatt scholars view Lydia's death as a major turning point in Mary's artistic career. Before Lydia became ill, there were no indications that Mary would become a "painter of mothers and infants." Cassatt did not display one of her signature "mother and infant"" paintings until the 1881 Impressionist exhibition. As noted earlier, the 1881 show was the venue for Autumn, a meditation on Lydia's imminent death.

Mary Cassatt's Mother and Child (Maternal Kiss), 1896

The Mary Cassatt whose art we know and love dates from the shocking loss of her sister. Inspired by Lydia's courage in the face of death, Mary chose life.as the theme of her art. As Radhakrishnan writes, Mary's paintings of the ailing, suffering Lydia were "foundational of the next chapter of her work."

Though she never married or had children of her own, Mary Cassatt created a special universe in her art where infants are nurtured by the strong and tender love of their mothers.

Gallery view of Mary Cassatt at Work,

Many children are not so blessed - or not to the same degree - as a "Mary Cassatt mother and child."

How wonderful it is, then, to behold such a pair in real life, walking down the street, in the playground or gazing at a Mary Cassatt painting in the local museum of art.

***

Text: Copyright of Ed Voves, all rights reserved. Photos by Anne Lloyd, all rights reserved

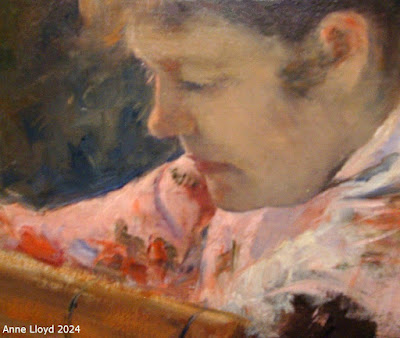

Introductory Image:

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024)

Gallery view of Mary Cassatt at Work showing Cassatt’s Lydia at a Tapestry Frame, 1880-81.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024) View

of the entrance to the Mary Cassatt at Work exhibition, Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024)

Mary Cassatt’s Woman in a Loge, 1879.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024)

View of Gallery 252 at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, showing the usual placement

of Mary Cassatt’s Woman in a Loge.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024)

Mary Cassatt’s Woman in a Loge as it

was displayed in 1879.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024)

Gallery view of the Mary Cassatt at Work exhibition.

Edgar Degas, (French,

18-1917) Mary Cassatt at the Louvre: the

Etruscan Gallery, 1870-1880.

Mary Stevenson Cassatt

(American, 1844-1926) Autumn, 1880.

Oil on Canvas: 93 x 65 cm. Musee du Petit Palais, Paris.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024)

Gallery view of Mary Cassatt at Work, showing paintings of Lydia Cassatt, dating to

1878-1880.

Mary Stevenson Cassatt

(American, 1844-1926) Lydia Seated in the

Garden with a Dog on Her Lap,

1878–79. Oil on canvas, 10 3/4 × 16 in. (27.3 × 40.6 cm). Cathy Lasry, New York.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024) Mary Cassatt’s Lydia

at a Tapestry Frame, 1880-81. Oil on Canvas: 65.5 x 92 cm. Flint Institute

of Arts, Michigan.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024) Mary Cassatt’s Lydia

Crocheting in the Garden at Marly, 1880. Oil on canvas: 25

13/16 x 36 7/16 in. (65.6 x 92.6 cm) Metropolitan Museum of Art. #65-124

Mary Stevenson Cassatt

(American, 1844-1926) Driving, 1881.

Oil on canvas, 35 5/16 × 51 3/8 in. (89.7 × 130.5 cm). Philadelphia Museum of

Art, W1921-1-1

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024)

Detail of Mary Cassatt’s Lydia at a Tapestry Frame, 1880-81.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024)

Detail of Mary Cassatt’s Mother and Child (Maternal Kiss), 1896.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024)

Gallery view of Mary Cassatt at Work, showing Cassatt’s Baby

Joan Nursing, 1908.

No comments:

Post a Comment