From Paris to Provence:

French Painting at the Barnes Foundation

June 29 - August 31, 2025

Reviewed by Ed Voves

Original Photography by Anne Lloyd

Art museums are oases of cultural and creative expression. On hot summer days, when throngs of vacationing art lovers make the trek in search of masterpieces, an art museum often is a literal oasis.The air conditioned galleries and cold drinks in the cafeteria are a welcome - and very needed - relief.

So it was, on a scorching late June morning, when we attended the press preview of the summer exhibition at the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia. It was fairly early in the morning, but an intensive heatwave was setting-in. It was "mad-dogs and Englishmen" weather, with hours to go until the "noon-day sun."

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025)

The press preview of Paris to Provence: French Painting at the Barnes

The subject of the summer exhibition is From Paris to Provence: French Painting at the Barnes. As the assembled journalists and photographers gathered to hear Dr. Cindy Kang provide a brilliant lecture on these signature Barnes art works, everyone looked positively revived. But when we reached the third gallery of the exhibition, dedicated to Van Gogh's paintings during his sojourn in Arles, I felt an irresistible urge to put my sunglasses back-on.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025)

Gallery view of Paris to Provence at the Barnes Foundation,

showing four paintings by Vincent van Gogh, 1888-1890.

There, set against the glaring backdrop of a Mediterranean summer hue, were four Van Gogh icons - and I don't use that word lightly.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025)

The four Van Gogh paintings shown above: Still Life (1888),

The Smoker (1888), The Postman (1889), Houses and Figure (1890).

Dr. Albert Barnes, with the advice and assistance of his friend, the artist William Glackens, purchased this select group of Van Gogh paintings. Because of the unique criteria of the Barnes Method, these Van Gogh paintings are rarely shown together. Indeed, this is likely the only time that they have ever been publicly displayed in this manner.

It was positively electrifying to see the four Van Gogh works at the press preview. Predictably, when my wife Anne and I returned for a follow-up visit, the number of art lovers lingering in front of these remarkable paintings never seemed to diminish.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025)

"Crowd pleasers" of the Paris to Provence exhibition,

Vincent van Gogh's The Smoker (1888) & The Postman (1889).

As unique as is the opportunity to view these Van Gogh paintings in their present setting, the motivation for this splendid exhibition is rather prosaic. The Barnes opened its doors on May 12, 2012. The wear-and-tear of ceaseless foot traffic necessitated a major rehab of the gallery floors.

Last summer's Matisse and Renoir exhibition presented an insightful look at the relationship of these two artists. All of the works on display came from the walls of second-floor galleries at the Barnes, while the floors were refurbished. This summer, it is the turn of the first floor galleries.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024)

View of a first floor gallery at the Barnes Foundation, the display of art works reflecting the principles of the Barnes Method.

The Barnes Method of display emphasizes the relationship of works of art based on "light, line, color and space." The arrangement of the "ensembles" of paintings, sculptures, ceramics, metalwork and hand-crafted furniture certainly encourages visitors to the Barnes to view these works from unconventional perspectives.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022)

An ensemble at the Barnes Foundation, showing

Van Gogh's The Postman displayed Renoir's Nude with Castenets (1918), Renoir still-lifes and a Windsor chair from the 1700's.

Originality of thought is, obviously, a good attitude to cultivate. Moreover, Dr. Barnes aimed to promote a democratic approach to culture. To Barnes, a carved Windsor chair from the 1700's was as worthy of study and appreciation as a Van Gogh portrait.

However, when one of the latter, in this case The Postman (Joseph-Etienne Roulin), is wedged in a corner to achieve the desire Barnes Method configuration, that can pose problems.

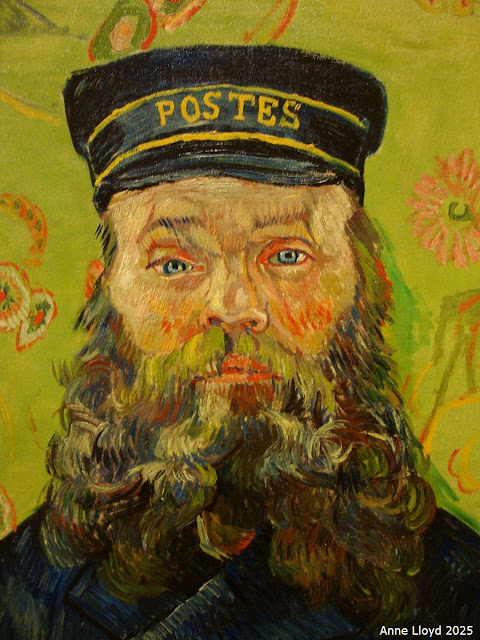

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025)

Vincent van Gogh’s The Postman (detail), 1889

Van Gogh painted six portraits of Roulin during the years, 1888-89, and the Barnes version is arguably the finest. The skill with which Van Gogh depicted Roulin's eyes is on such a transcendent level that clearly it was based on much more than technical skill. But if you wish to subject The Postman to prolonged appraisal in its usual setting, you risk a "crick" in the back or eye strain.

Paris to Provence provides a precious opportunity to encounter The Postman "face-to-face." At the same time, you can attempt to fathom the intangible bond between Van Gogh and Roulin which is reflected in this astonishing - yes, "iconic" - portrait.

This holds true for the other nearby Van Gogh paintings, including (or perhaps, especially) Houses and Figure which seems to be shrinking in the intense summer heat.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025)

Gallery views of Van Gogh’s Houses and Figure, 1890

From Paris to Provence is much more than a golden opportunity to display signature works from the Barnes collection in a popular summer offering. It is a brilliantly curated exhibition charting the rise and progress of modern art in Belle Époque France.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025)

Pierre-August Renoir's Girl with a Jump Rope (detail), 1876

The exhibition begins with a series of Renoir portraits from the 1870's and several works by Manet, an artist seldom associated with the Barnes collection. These highly accomplished works symbolize the rapid recovery of the self-confidence and prosperity of France following the disastrous Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025)

Claude Monet's The Studio Boat (detail), 1876

Impressionism, the "new painting", spread from Paris to the surrounding countryside. The Barnes exhibit takes note of this trend with a painting of Claude Monet working in his Studio Boat near Argenteuil on the River Seine. From there, the Impressionists and post-Impressionists sought new subjects in Normandy and Brittany. The next, bold move was southward to Provence, where the tragic Van Gogh/Gauguin episode took place.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025)

Gallery view of Paul Cézanne's Bathers at Rest, 1876-77

At this point in Paris to Provence, the reclusive Cézanne takes center stage. Choosing wisely from the incomparable holdings of Cézanne's oeuvre in the Barnes collection (61 oil paintings and 8 of his works on paper), Dr. Kang was able to illustrate the extraordinary scope of Cézanne's genius.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025)

Two Cézanne paintings on view in Paris to Provence:

Terracotta Pots and Flowers, 1891-92, & Bibemus Quarry, c. 1895

This brief synopsis of the exhibition is hardly "breaking" news for art enthusiasts. What is worthy of remark is the way that this time-honored narrative of early Modernism is illustrated with works from the Barnes. The result is a striking visual reinterpretation which presents a familiar story in a new light.

The selection of works of art for presentation in a special exhibition is always a complex process. In one sense, the task of the Barnes curatorial staff is both simplified and complicated by the fact that only paintings from the first floor galleries could be used. It says a lot about the strength of the Barnes collection that - under these restrictions - fifty outstanding works could be selected to illustrate the Paris to Provence theme.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025)

View of the Paris to Provence exhibition: (from left) Henri Matisse's

Blue Still Life (1907) & Renoir's Nude in a Landscape, c. 1917

Yet there was a further challenge in the selection process. One of the leading figures in the southward shift was Henri Matisse. Along with Renoir, Matisse was the protagonist of last summer's exhibit, as noted earlier. Although there are several Renoir paintings in From Paris to Provence, the decision was made to limit Matisse's contribution to just one.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025)

Henri Matisse's Blue Still Life, 1907

The choice was a wise one: Matisse's Blue Still Life. Painted in 1907, it is a sensational "balancing act", contrasting the bright Mediterranean light with deep shadow. Additionally, Blue Still Life has several of the defining hallmarks of Matisse's oeuvre, notably his love of fabrics and astute interior design sense.

One of the reasons for restricting the number of Matisse paintings and thereby conserving available wall space becomes apparent in the last gallery. Here paintings by emigre artists like Amadeo Modigliani, Chaim Soutine, Georgio de Chirico and Joan Miro are displayed.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025)

The final gallery of Paris to Provence, showing (from left) Modigliani's Girl with a Polka-Dot Blouse (1919), Soutine's Woman in Blue (1919)

and Modigliani's Portrait of the Red-Headed Woman (1918)

Dr. Cindy Kang explained one of the important results of widening the focus of French art beyond the orbit of Paris. This was to create works of art which appealed to and influenced a new generation of artists at the dawn of the twentieth century. Many of these artists reversed the "southward shift" and made Paris their base of operation.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025)

Dr. Cindy Kang at the press preview of Paris to Provence

Much of the work of this new "School of Paris" would prove unintelligible and infuriating to the French artistic establishment and public-at-large. De Chirico's cryptic Sophocles and Euripides perhaps explains why.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025)

Giorgio de Chirico's Sophocles and Euripides, 1925

As alien and unsettling as some of the paintings in the final gallery of Paris to Provence may appear, their presence should not be unexpected. The late 19th century in France is known as the Belle Époque, but much of the beauty and joie de vivre of the era was dearly bought.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025)

Vincent van Gogh's The Factory, 1887

Along with the four sun-drenched Provencal paintings, there is another Van Gogh which shows a grim industrial site in the suburbs of Paris.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025)

Detail of Cézanne's Young Man and Skull, 1896-98

Nor can the sobering sight of human skulls in two of the Cézanne paintings be ignored. This was a reference to the omnipresence of death even in paradise-like surroundings - Et in Arcadia ego. For Cézanne, who aimed to paint works of art worthy of display in the Louvre, this was likely an homage to the famous paintings by Nicholas Poussin (1637-38) on this grim theme.

It would, however, be quite inappropriate to end this review of Paris to Provence on a melancholy note.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025)

Visitors to the Paris to Provence exhibition,

admiring Édouard Manet's Laundry, 1876

The French painters, whose works are so beautifully displayed in this wonderful exhibition, traveled the road from Paris to Provence in search of light. The foreign artists who responded - Modigliani, Soutine, Miro, De Chirico and others (like Chagall) not represented in the exhibit - chose to paint in Paris because it was the City of Light.

And where there is light, there is art and life.

***

Text: Copyright of Ed Voves, all rights

reserved.

Original photography, copyright of Anne

Lloyd, all rights reserved.

Introductory Image:

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025) Pierre-August Renoir's Luncheon, 1875. Oil on canvas: 19 3/8 x 23 5/8 in. (49.2 x 60 cm) BF45

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025) The press preview of From Paris to Provence: French Painting at the Barnes.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025) Gallery view of Paris to Provence at the Barnes Foundation, showing four paintings by Vincent van Gogh, 1888-90.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025) Four paintings by Vincent van Gogh: Still Life (1888), The Smoker (1888), The Postman (1889) and Houses and Figure (1890).

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025) "Crowd pleasers" of the Paris to Provence exhibition, Vincent van Gogh's The Smoker (1888) & The Postman (1889)

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025) View of a first floor gallery at the Barnes Foundation, the display of art works reflecting the principles of the Barnes Method.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025) An ensemble at the Barnes Foundation, showing

Van Gogh's The Postman displayed Renoir's Nude with Castenets (1918), Renoir still-lifes and a Windsor chair from the 1700's.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025) Detail of Van Gogh's The Postman (Joseph-Etienne Roulin), 1889. Oil on canvas: 25 7/8 x 21 3/4 in.

(65.7 x 55.2 cm). BF37

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025) Gallery views of Van Gogh’s Houses and Figure, 1890. Oil on canvas: 20 1/2 x 15

15/16 in. (52 x 40.5 cm). BF136

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025) Pierre-Auguste Renoir's Girl with a Jump Rope: Portrait of Delphine Legrand (detail), 1876. Oil on canvas: 42

1/4 x 27 15/16 in. (107.3 x 71 cm) BF137

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025) Detail of Claude Monet's The Studio Boat. Oil on canvas: 28 5/8 x 23 5/8 in. (72.7 x 60 cm) BF730

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025) Gallery view of Paul Cézanne's Bathers at Rest, 1876-77. Oil on canvas: 32

3/8 × 39 13/16 in. (82.2 × 101.2 cm) BF906

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025) Two Cézanne paintings on view in Paris to Provence: Terracotta Pots and Flowers, 1891-92 (Oil on canvas: 36

3/8 × 28 7/8 in. (92.4 × 73.3 cm) BF235 ), & Bibemus Quarry, c. 1895 (Oil on canvas: 36

1/4 × 28 3/4 in. (92 × 73 cm) BF 34)

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025) View of the Paris to Provence exhibition: (from left) Henri Matisse's Blue Still Life (1907) & Renoir's Nude in a Landscape, c. 1917.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025) Henri Matisse's Blue Still Life (1907). Oil on canvas: 35

5/16 × 45 15/16 in. (89.7 × 116.7 cm) BF185

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025) The final gallery of Paris to Provence, showing (from left) Modigliani's Girl with a Polka-Dot Blouse (1919), Soutine's Woman in Blue (1919) and Modigliani's Portrait of the Red-Headed Woman (1918).

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025) Dr. Cindy Kang at the press preview of Paris to Provence.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025) Giorgio de Chirico's Sophocles and Euripides, 1925. Oil on canvas: 28 7/8 × 23

5/8 in. (73.3 × 60 cm) BF575

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025) Vincent van Gogh's The Factory, 1887. Oil on canvas: 18

1/8 x 21 7/8 in. (46 x 55.6 cm) BF303

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025) Detail of Cézanne's Young Man and Skull, 1896-98. Oil on canvas: overall: 51

3/16 x 38 3/8 in. (130 x 97.5 cm) BF929

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025) Visitors to the Paris to Provence exhibition, admiring Édouard Manet's Laundry, 1876. Oil on canvas: 57

1/4 x 45 1/4 in. (145.4 x 114.9 cm) BF957