Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024)

Henri Matisse’s Le Bonheur de vivre, (The Joy of Life),1905-1906

With Renoir, Barnes

obviously purchased his works with personal passion, rather than strictly critical

appraisal. Barnes admitted as much. There are many masterpieces by Renoir,

however, among the astonishing array amassed by Dr. Barnes.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024)

Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s Leaving the Conservatory, 1876–1877

As noted by the exhibition

curators, Barnes favored Renoir’s later works rather than those painted during

the early years of Impressionism.Two of the most significant works by

Renoir in the exhibit, however, date from the 1870s. Renoir's late works, celebrating the female nude, would fall into disfavor, as did similar paintings by Matisse,especially from the 1920's. Barnes seldom heeded the critical opinions of others and kept buying works by both artists.

It is, thus, almost impossible to

consider Renoir and Matisse without some acknowledgement of the role of Dr.

Barnes as collector. However, there is another aspect of this artistic

“three-some” that is more problematical. The “Barnes Method” of presenting art does

not always work to the advantage of individual paintings or sculptures when

appreciated on their own merits.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022)

Gallery view of the Barnes Foundation. Matisse's Two Young Girls in a Red and Yellow Interior,1947, appears above a 1700's Slant-top Desk

Dr. Barnes’ technique

emphasized group or “ensemble” displays, a juxtaposing of celebrated oil

paintings with smaller works on paper, folk art, ancient artifacts, hand-crafted

furniture and utensils from daily life.

A good example of this approach

is the ensemble anchored by Renoir’s Mussel-Fishers

at Berneval (1879). It is one of the key works by Renoir on view in Matisse & Renoir: New Encounters.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024)

Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s Mussel-Fishers at Berneval, 1879

As it usually appears on the

second floor of the Barnes Foundation, Renoir’s impressive depiction of

children from a coastal fishing village in Normandy is hung above an 18th

century Pennsylvania German wooden chest. Displayed on the chest are pewter

vessels and redware ceramic objects from the 1800’s. In close proximity are 16th

century iron andirons.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024)

Gallery view of the Barnes Foundation, showing the usual ensemble display of Renoir's Mussel-Fishers at Berneval, 1879

This visual orchestration certainly creates an

atmosphere of rustic charm surrounding Mussel-Fishers at Berneval, though I am not sure if that was Dr. Barnes' intention. Whatever the organizational planning for this ensemble, I never cease to be impressed by it when

visiting the Barnes.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024)

Gallery view of Matisse & Renoir: New Encounters at the Barnes,

showing (from left) Renoir’s Prominade, 1905, Mussel-Fishers at Berneval, and Leaving the Conservatory, 1876–1877

Renoir’s Mussel-Fishers at Berneval is presented

in a very different manner in the current exhibition. It is mounted between the 1905 portrait of Renoir's young son, Claude, and his nurse, Prominade, and Renoir's Leaving the Conservatory from 1876-77. In keeping with modern-day

museum standards, it is a graceful and spacious arrangement. But it

certainly is not in “sync” with the Barnes method.

Why did the curators of Matisse & Renoir: New Encounters depart from the Barnes method? A

very prosaic reason, rather than an abrupt change in institutional policy,

provides the answer.

The Barnes Foundation opened its center-city Philadelphia

location on May 12, 2012. Over a decade of heavy-foot traffic necessitated

refinishing work on the upper-level floors of the building.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022)

Gallery view of the Barnes Foundation, showing Matisse’s Three Sisters (Les Trois soeurs) in their usual display configuration

Rather than put all

of the beloved works of art in storage, a brilliant alternative was found:

mount a special exhibition of the second-floor paintings by Renoir and Matisse,

a display which would recall their friendship during the final years of the

“war to end all wars.”

In 1917, Matisse traveled to the south of France for a respite from the stresses of the war. He had been rejected from military service

because of his age and health, but members of his family were trapped behind

German lines and one his sons was serving in the French army, the

second soon to follow.

The initial meeting on December 31, 1917, at Renoir’s home

at Les Collettes, was strained. Renoir nursed some lingering

resentment for Matisse, leader of the Fauves. Matisse and his “wild beast”

colleagues had undermined the Impressionist aesthetic of “on-the-spot” depiction

of the transitory state of nature.

"Impressionism is the newspaper of the soul," Matisse had declared, a remark which left a lot of room for interpretation.

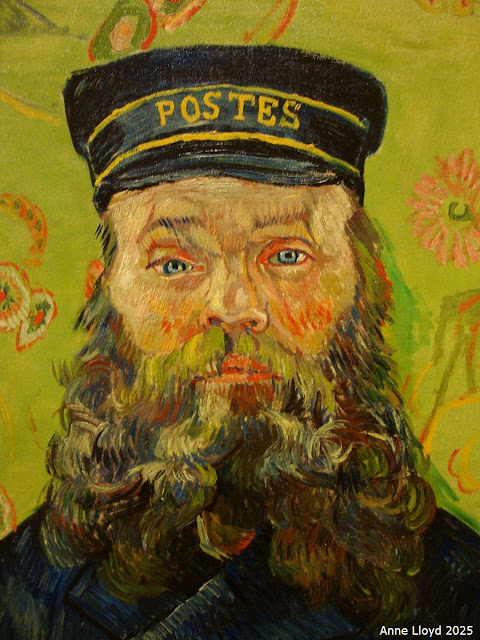

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024)

Detail of a 1917 photo of Henri Matisse & Pierre Renoir

Matisse and Renoir quickly warmed

to each other. Thereafter, Matisse visited often, especially as Renoir, wracked

with pain, neared death in 1919. How could an artist of great soul like Matisse

resist the withered little man of unquenchable spirit who proclaimed, “The pain passes, Matisse, but

the beauty remains.”

Matisse could not resist and neither

will you, if you are fortunate to visit the Barnes for this unusual

presentation of masterworks by Renoir and Matisse.

The curators of this

wonderful exhibition, Cindy Kang and Corinne Chung, did resist a contemporary trend in gallery display. This is the

“in-dialog” methodology of hanging two (seemingly) similar paintings by

different artists, side-by-side. The rival paintings can then “duke-it-out”, at

least in the minds of inquisitive patrons.

Instead, the Barnes curators chose a chronological approach, with alternating galleries devoted to works by Renoir and then to Matisse. This enables us to trace the development of both artists up to their tense introduction on New Years Eve 1917. Crucially for Matisse, this presentation model informs our appreciation of the continuing evolution of his art after Renoir's death.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024)

Cindy Kang discussing works by Renoir at the press preview for

Matisse & Renoir: New Encounters at the Barnes

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024)

Gallery view of Matisse & Renoir: New Encounters at the Barnes, showing Matisse’s Three Sisters (Les Trois soeurs) series,1917

There certainly are "pros" as well as "cons" for the in-dialog display technique. It is interesting to speculate on whether that might have worked in the case of Matisse & Renoir: New Encounters at the Barnes.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2023)

Gallery view of Manet/Degas at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Met’s 2023 Manet/Degas utilized the in--dialog approach and it

succeeded brilliantly. Of course, Manet and Degas were rivals – “frenemies” –

and direct comparison of their works was appropriate. The same was true for MOMA's exhibit back in 2005 devoted to the painting sojourns of Cezanne and Pissarro in Pontoise during the 1870's. Painting with Pissarro as his companion and mentor helped liberate Cezanne's art.

The irony of Matisse & Renoir: New Encounters at the Barnes is that the relationship of the two painters was a true dialog about art. Matisse and Renoir covered a wide expanse of topics in their conversations. Renoir still had a sharp mind, an earthy sense of humor and, with two sons recovering from war wounds, a bitter attitude about the futile "meat-grinder" tactics of the Great War.

"Renoir," Matisse recalled, "said it should be the old and infirm sent to die in holes, not the young with their lives before them."

The best place to consider the "dialog" between Matisse and Renoir - in conjunction with the Barnes exhibit - is Hilary Spurling's biography, Matisse the Master, published in 2005. Two short excerpts from this wonderful book will suffice to set the tone of the encounters between these masters of art:

He (Matisse) came regularly in the early evening to sit with the old man, who was gripped as the light faded by dread of the night's suffering ahead. They swapped gossip, told frisky stories, compared notes about their beginnings (Renoir said he spent the proceeds from his first picture sales on a sack of haricot beans to feed his children.) ... They discussed technique, reputation, posterity, the whole question of shifting focus and vision that had been the main battlefield for their two generations.

One of the prime subjects of conversation was Renoir's work-in-progress, Composition, Five Bathers. This Arcadian scene of nudes in the Rubins' tradition was Renoir's response to the horrors of death and suffering which had engulfed the world in 1914 - and to his own private, physical suffering.

Matisse thought highly of Renoir's Composition - Five Bathers. So did Dr. Barnes, who purchased the now controversial painting.It can be seen in a nearby gallery in the Barnes regular, first floor, exhibition area.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024)

Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s Bather Gazing at Herself in the Water, 1910

Dr. Barnes bought quite a number of Renoir's late nudes, like Bather Gazing at Herself in the Water, from 1910, on view in the exhibition. The esteem of Barnes and Matisse for these robustly-figured nudes is shared by few today. A similar cloud of disapproval likewise shrouds the nudes and scantily-clad odalisques which absorbed much of Matisse's time and energy during the 1920's.

Whatever one's reaction to a work like Moorish Woman (The Raised Knee), Matisse's career path had been largely decided by one of his signature works in the Barnes Collection, created at the height of the Fauvist revolution.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024)

Henri Matisse’s Red Madras Headdress, 1907

Matisse”s

Red Madras Headdress (Le Madras rouge) was painted between the end of April and

mid-July 1907. An earlier, more sketch-like version was created shortly before.

This portrait of Matisse’s wife, Amélie,

is one of his greatest works, setting a standard of achievement which Matisse was to struggle to match for many years thereafter.

Red Madras Headdress is a work of great psychological insight,

almost a signature portrait of European identity at the start of the twentieth

century. Clad in an exotic head scarf, Matisse’s protagonist (Amélie) radiates independence, candor, skepticism and more than a touch of coy sensuality.

Temporarily

liberated from its crowded “Barnes Method” location, Red Madras Headdress asserts

itself as one of the great works of Matisse. This is the face of the young, self-confident twentieth century, painted by the "King of the Fauves."

The uncluttered placement of Red Madras Headress allows

us to raise a further issue. Why did Matisse not follow-up this striking

portrait with more of the same caliber? In fact, Matisse would never again paint such

a portrait, with this level of bold, direct articulation of the modern spirit.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024)

Gallery view of Matisse & Renoir: New Encounters at the Barnes, showing Matisse’s Red Madras Headdress

In the years

after he painted Red Madras Headdress, Matisse began to explore different, less

radical paths for creating art. The social implications of Modernism were

becoming obvious – and not all were reassuring to him. Though interested in Cubism, Matisse did not embrace the new movement nor any of the other "isms" which followed.

In 1908, Matisse wrote

an essay whose most famous statement would be used by art critics and avant

garde artists to denounce and heap scorn upon him.

“What I dream of is an art of balance, of

purity and serenity, devoid of troubling or depressing subject matter, a

soothing, calming influence on the mind, rather like a good armchair which

provided relaxation from physical fatigue.”.

Matisse may well have regretted the "armchair" example (it is sometimes omitted from the quote). For Matisse, the years just prior and, especially, during World War I were marked by a search for "an art of balance, of purity and serenity."

This search brought Matisse to the door of Renoir's home on New Year'a Eve, 1917. There he found an arthritic old man with a paint brush tied to bandaged fingers, painting his vision of Arcadia.

Years later, during the aftermath of World War II, Matisse would follow Renoir's lead and paint a series called the Vence Interiors.

Henri Matisse’s Two Young Girls in a Coral Interior, Blue Garden, 1947

Elderly, careworn, still suffering from a near-death encounter with cancer in 1941, Matisse could not even stand for long periods in front of an easel. Yet, he finally achieved his aim of creating images of "balance, of purity and serenity."

Across the Atlantic Ocean, Dr. Albert Barnes took note and purchased two of the Vence Interiors. These were to be the last works by Matisse to enter the Barnes Collection. These small, meditative paintings are the perfect works of art to conclude Matisse & Renoir: New Encounters at the Barnes.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024)

Gallery view of Matisse & Renoir: New Encounters at the Barnes,

showing two of Matisse's Vence Interiors

Perfect works too, to illustrate Matisse's indomitable creative spirit and how he came to embody, how he came to live Renoir's immortal words, “The pain passes, Matisse, but the beauty remains.”

***

Text: Copyright of Ed Voves, all rights

reserved

Original photography, copyright of Anne

Lloyd

Introductory and first image: Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024) Henri Matisse’s Le Bonheur de vivre,

also called The Joy of Life, between October 1905-1906. Oil on canvas Overall: 69

1/2 x 94 3/4 in. (176.5 x 240.7 cm) The Barnes Foundation

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024) Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s Leaving the Conservatory (La Sortie du

conservatoire), 1876–1877 Oil on canvas: 73 13/16 x 46 1/4 in. (187.5 x

117.5 cm) The Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024) Gallery view of Matisse's Two Young Girls in a Red and Yellow Interior, 1947, appears above a 1700's Slant-top Desk.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024) Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s

Mussel-Fishers at Berneval (Pêcheuses de moules à Berneval, côte normand) 1879. Oil on canvas: 69 3/8 x 51 1/4 in. (176.2 x 130.2 cm) The Barnes Foundation

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024) Gallery view of the Barnes Foundation, showing the usual ensemble display of Renoir’s Mussel-Fishers at Berneval, 1979.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024) Gallery view of Matisse & Renoir: New Encounters at the Barnes, showing (from left) Renoir’s Prominade, 1905, Mussel-Fishers at Berneval.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024) Gallery view of Matisse & Renoir: New Encounters at the Barnes, showing (from left) Renoir’s Prominade, 1905, Mussel-Fishers at Berneval, and Leaving the Conservatory, 1876–1877

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024) Detail of a 1917 photo of Henri Matisse and Pierre-Auguste Renoir.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024) Dr. Cindy Kang of the Barnes Foundation, discussing works of art by Renoir at the press preview of Matisse & Renoir: New Encounters at the Barnes.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024) Gallery view of Matisse & Renoir: New Encounters at the Barnes, showing Henri Matisse’s Three Sisters (Les Trois soeurs) series, painted between April to mid-July 1917. The Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2023) Gallery view of the Manet/Degas exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024) Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s Bather Gazing at Herself in the Water, 1910. Oil on canvas: 25 13/16 x 32 in. (65.5 x 81.3 cm)

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024) Henri Matisse’s Red Madras Headdress (Le Madras rouge), painted between the end of April and mid-July 1907. Oil on canvas: 39 3/8 x 31 7/8 in. (100 x 81 cm) The Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024) Gallery view of Matisse & Renoir: New Encounters at the Barnes, showing Matisse's Red Madras Headdress.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024) Henri Matisse’s Two Young Girls in a

Coral Interior, Blue Garden (Deux fillettes, fond corail, jardin bleu), Between

May-June 1947 Oil on canvas Overall: 25 1/2 x 19 5/8 in. (64.8 x 49.8 cm) The Barnes Foundation

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024) Gallery view of Matisse & Renoir: New Encounters at the Barnes, showing two of Matisse's Vence Interiors.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)