"Mirror of the Soul"

Reflections on the Barnes Foundation's Paris to Provence Exhibition

Text by Ed Voves

Original Photography by Anne Lloyd

In a December 1885 letter to his brother, Theo, Vincent van Gogh composed one of his most poignant statements on his aims as an artist:

"I'd rather paint people's eyes than cathedrals," Van Gogh stated, "for there's something in the eyes that isn't in the cathedral ... to my mind the soul of a person ... is more interesting."

While reading this heartfelt statement, one almost senses that the Dutch painter will continue his reflections with a paraphrase of the often-quoted proverb, "the eyes are the mirror of the soul."

Van Gogh did not pursue the eyes/soul theme or use the analogy of mirror in his 1885 letter to Theo. Earlier, in 1877, he did write in this vein to his brother - as we will discuss momentarily. But when I stood before Van Gogh's portrait of Joseph-Etienne Roulin, on view in a special exhibition at the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia, these words soon came to mind and have been much in my thoughts since then.

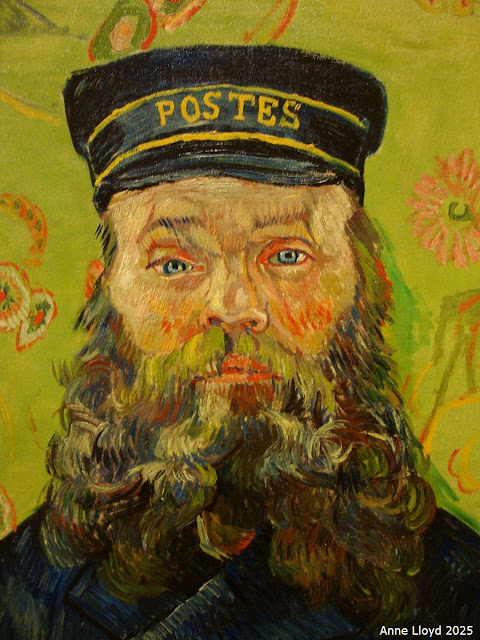

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025)

Vincent van Gogh's The Postman (Joseph-Etienne Roulin),1889

Van Gogh's "Postman" was the anchor work of art in a spectacular four-painting ensemble in the just concluded From Paris to Provence exhibition at the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia. In the Art Eyewitness review of this wonderful exhibit, I commented on the special insights afforded to this portrait by a change from its normal Barnes Method presentation. I won't belabor that point further.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025)

Gallery view of Paris to Provence, showing

Van Gogh's Still Life (1888), The Smoker (1888), The Postman (1889)

and Houses and Figure (1890).

Oddly enough, it was not the way that Joseph-Etienne Roulin was hung in the exhibition that occasioned my reflections on the eyes of this iconic portrait. Instead, it was a very unusual design feature in the layout of Paris to Provence in the Roberts Gallery of the Barnes which led to a train of thought which, to be honest, I had not been expecting.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025)

Gallery view of Paris to Provence at the Barnes Foundation, showing

an example of a "cut-out" or "window" exhibition feature

Known colloquially as "cut-outs" or "windows", these openings in gallery walls create lines of sight which can totally transform exhibit spaces. The Met used this technique to brilliant effect in its 2022 Winslow Homer exhibition.

Gallery view of the Winslow Homer: Crosscurrents exhibit at The Met

Instead of keeping us "imprisoned" within four walls and a ceiling, the special exhibition gallery now opens our eyes and minds to unusual sights, unorthodox angles of observation and unexpected impressions and thoughts. This process sounds more dramatic than it is in practice, which transpires at several degrees below our conscious awareness.

Yet, these "cut-outs" can powerfully affect our perception and help transform a visual encounter with works of art into a visionary experience.

For that to happen, we need to augment the influence of sophisticated design techniques like "cut-outs" with an appreciation of the work of art we are examining. This includes the social and spiritual realms which the artist and his subject inhabit, as well as the exterior setting around them.

To help us comprehend this complex interplay of outer environment and inner character traits, another quote from Vincent van Gogh is in order. This reflection dates to 1877, when Van Gogh worked in an art dealership in London. In a letter to his brother, Theo, Van Gogh wrote,

"The souls of places seem to enter the souls of men, so often from a barren, dreary region there emerges a lively, ardent and profound faith. As the place, so the man. The soul is a mirror first, and only then a seat of feeling."

To test Van Gogh's theories on how the circumstances of the world around us enter into the "souls of men", let's compare the Barnes Foundation's portrait of Joseph-Etienne Roulin with two others which the Dutch artist painted of the French postal official (of a total of six).

Shortly after arriving in Arles during the winter of 1888, Van Gogh became acquainted with Joseph-Etienne Roulin (1841-1903) and established a close friendship. Early on, he painted an impressive, almost heroic-scale, portrait of Roulin in his dark blue postal uniform, which gave him the air of a rugged sea-captain.

Vincent van Gogh, Postman Joseph Roulin, 1888

This portrait, one of the treasures of the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, presents Roulin in an introspective mood. His eyes are not focused on Van Gogh, but looking inward. That is certainly not the case with a tightly-cropped portrait of Roulin, painted around the same time. It has the hard, almost defensive, stare of a passport photo.

It is this second work, from the collection of the Detroit Institute of Art, which best serves as a foil to the Barnes portrait of Roulin, which was painted in the spring of 1889. The two works, studied in contrast, exemplify Van Gogh's 1877 reflections on how the "soul is a mirror first, and only then a seat of feeling."

Van Gogh's Portrait of the Postman Joseph Roulin, 1888,

from the Detroit Institute of Art, (left) contrasted with the Barnes Foundation's The Postman (Joseph-Etienne Roulin), 1889.

We know from Van Gogh's letters to Theo that it took him a while to get the measure of Roulin. Initially, he matter-of-factly described Roulin as a "man more interesting than most."

By the time he painted Roulin in the spring of 1889. Van Gogh's tone had completely changed. Roulin had devotedly aided him during the terrible emotional breakdown triggered by the dispute with Gauguin. Even after he was transferred to duty in Marseilles, Roulin returned to Arles to visit Van Gogh, as he struggled to regain control of his life. Now, Roulin is described as having "the salient gravity and a tenderness for me such as an old soldier might have for a younger one."

Gravity and tenderness, along with concern, sorrow and perhaps, a touch of fear. These emotions are visibly present in the "mirror" of Roulin's eyes. An intelligent man, with considerable life experience, Roulin likely suspected that Van Gogh's recovery would be a difficult process.

There can be absolutely no doubt that the experience of his friendship with Roulin had registered in Van Gogh's soul as "a seat of feeling." Van Gogh signed the Barnes Foundation portrait, "Vincent." It was the only one of his six portraits of Roulin to be signed.

Van Gogh captured the essence of Roulin's character and inner spirit, making this work one of the greatest portraits in European art during the "long" 19th century. Having acknowledged Van Gogh's achievement, it also needs to be emphasized that From Paris to Provence gave plenty of scope to his contemporaries as portrait painters. Renoir, Cezanne, Gauguin and later Modigliani and Soutine, each in their unique way, devoted themselves to depicting their subjects - body and soul.

The opening gallery of Paris to Provence presented a choice selection of portraits by Renoir, a portrait by Cézanne of his wife (which, like many a Cézanne, seems more of a work-in-progress than a finished painting) and an intriguing genre scene by Manet. All are works of enduring merit.

Gallery view of the Paris to Provence exhibition, showing Renoir's Portrait of

Jeanne Durand-Ruel, 1876

Given our theme of the eyes as "mirror of the soul," Renoir's portraits of two young girls, each the daughter of a prominent art dealer, command our attention.

Details of Renoir's Portrait of Jeanne Durand-Ruel, 1876, &

Girl with a Jump Rope: Portrait of Delphine Legrand, 1876

The girl on the left, Jeanne Durand-Ruel (1870-1914), was the daughter of Paul Durand-Ruel, the principal dealer of Manet and the Impressionists, including Renoir. On the right is Delphine Legrand, whose father, Alphonse Legrand, helped organize the Second Impressionist Exposition. This occurred in 1876, the year Renoir painted both portraits.

Renoir is said to have left the choice of clothing to the subjects who sat for their portraits. In the case of these children, the selection would have been made by their parents. The decision to dress the six-year old Jeanne in a bare-shouldered ball dress seems out-of-character for a level-headed business man and staunch Catholic like Durand-Ruel. Whatever motivated the choice of this dress, the result was to make little Jeanne look "living-doll" cute but also vulnerable, rather than grown-up and beautiful.

The blue smock, worn by Delphine, was a more sensible choice. Even grasping a jump-rope, she projects a mature personna. Looking at Delphine Legrand, one senses that this little girl is quite capable of handling herself in her social milieu.

Close-study of the faces and eyes of Jeanne and Delphine confirm what marvelous portraits these are. Renoir succeeded in capturing the real character of each girl and evoking their individual souls as "a seat of feeling." Jeanne's eyes are compelling and appealing; Delphine's are alert, aware and self-assured.

Or so it seems - and this is an important point to consider.

If we continue to hearken-back to the proverb, "the eyes are the mirror of the soul," we need to reflect on what this means. Proverbs, like the Oracle of Delphi, are open to interpretation.

Who is reflected in the mirror of Jeanne's and Delphine's eyes? The young girls themselves? Renoir, who painted them? We, the art lovers who study them?

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025)

Cézanne's Madam Cézanne, 1888-1890, Barnes Foundation

Continuing in this train of thought, who is mirrored in the dull, dark eyes of Madam Cézanne? Displayed in the same gallery as the Renoir portraits just described, Cézanne's painting appears to come from a completely different artistic convention and an alien way of thinking.

Cézanne could paint endearing and character-affirming portraits - when he was moved to do so. He demonstrated his versatility with Madam Cezanne with Her Hair Down, from the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. This was created shortly after the Barnes Foundation portrait with its grim, sullen expression, dating to 1890.

Cézanne's Madam Cézanne with Her Hair Down, 1890

Philadelphia Museum of Art collection

Cézanne's rationale for depicting the human countenance according to the dictates of mood and feeling is memorably described by his biographer, Alex Danchev:

A Cézanne portrait is more a thereness than a likeness. The mature Cézanne scorned mere likeness ... The portraits he preferred were the ones that showed temperament...

Inscrutable though the Barnes' portrait of Madame Cézanne may appear, we should resist concluding that personal factors or traces of marital discord influenced the way her husband depicted her. Cézanne had other motives. He was pushing art into uncharted regions, toward discovering a "thereness."

Sentimentality had little place in Cézanne's artistic calculations. He adored his son, Paul. Yet the numerous portraits and sketches of Paul displayed in the National Gallery exhibit, Cézanne's Portraits (2018), and MOMA's Cézanne Drawing (2021) feature a circumscribed range of emotions much like those in paintings of his mother. No beaming eyes or charming smiles that I can recall.

Instead of sentimentality in his portraits, Cézanne responded to sensations.

"I paint as I see, as I feel," Cézanne declared early in his career, "and I have very strong sensations."

It was these sensations and Cézanne's rigorous determination to depict them on his canvas which drew the attention of the succeeding generation of artists to follow his example, if not his techniques.

In the final gallery of From Paris to Provence, the legacy of Renoir, Van Gogh and - especially - Cézanne was seized-upon and radically re-envisioned by the School of Paris artists.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025)

View of the final gallery of From Paris to Provence, showing (from left) Modigliani's Girl with a Polka-Dot Blouse (1919), Soutine's Woman in Blue (1919) & Modigliani's Portrait of the Red-Headed Woman (1918)

Of this avant-garde group, Modigliani and Soutine worked with an almost reckless disregard for convention and their own health. They sought to integrate new influences into the art of portraiture - African masks, unsettling theories about human thought, emotion and sexuality, the impact of World War I - to promote the grand traditions of French art for a new century.

To a remarkable degree, the School of Paris painters, with hardly a Frenchman in their ranks, made a lasting impact on the world of art.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025)

Details of portraits by Amadeo Modigliani and Chaim Soutine: Modigliani's Portrait of the Red-Headed Woman (1918)& Girl with a Polka-Dot Blouse (1919); Soutine's Woman in Blue (1919)

By the time this essay is posted, all of the works of art displayed in From Paris to Provence will have been rehung in their accustomed places on the gallery walls of the Barnes. Most had not been moved from their prescribed configuration since the 1993 international exhibition of Barnes Foundation works of art.

Van Gogh's "Postman" will return to its cramped position behind an 18th century Windsor chair and Delphine Legrand will hop and skip with her jumping rope over a painted wooden chest, made by Pennsylvania Dutch craftsmen in 1792.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025)

Visitors to the Barnes Foundation, viewing works of art in the Main Room, north wall, of the museum

However, don't expect the situation at the Barnes to be exactly as it was before From Paris to Provence. This is especially true, if you had the good fortune to visit this superb exhibition.

Once you look in the mirror of a person's eyes and catch a glimpse of their soul - or a reflection of your own - things are never quite the same again.

***

Text: Copyright of Ed Voves, all rights

reserved

Original photography, copyright of Anne

Lloyd

All works of art, unless otherwise noted are from the Barnes Foundation collection

Introductory Image:

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025) Detail of Pierre-August Renoir's Portrait of Jeanne Durand-Ruel, 1876.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025) Vincent van Gogh's The Postman (Joseph-Etienne Roulin), 1889. Oil on canvas: 25 7/8 x 21 3/4 in. (65.7 x 55.2 cm).

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025) Gallery view of Paris to Provence at the Barnes Foundation, showing four paintings by Vincent van Gogh: Still Life (1888), The Smoker (1888), The Postman (1889) and Houses and Figure (1890).

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025) Gallery view of Paris to Provence at the Barnes Foundation, showing an example of a "cut-out" or "window" exhibition feature.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) Gallery view of the Winslow Homer: Crosscurrents exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Vincent van Gogh (Dutch, 1853-1890) Postman Joseph Roulin, 1888. Oil on canvas: 32 x 25 3/4 in. (81.3 x 65.4 cm). Museum of Fine Arts Boston.

Vincent van Gogh (Dutch, 1853-1890) Portrait of the Postman Joseph Roulin, 1888. Oil on canvas: 25 9/16 x 19 7/8 in. (65 x 50.5cm). Detroit Institute of Art.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025) Gallery view of the Paris to Provence exhibition, showing exhibition entrance and Pierre-Auguste Renoir's Woman with a Fan.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025) Gallery view of the Paris to Provence exhibition, showing Pierre-Auguste Renoir's Portrait of Jeanne Durand-Ruel, 1876.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025) Details of Renoir's Portrait of Jeanne Durand-Ruel, 1876. 44 7/8 x 29 1/8 in. (114 x 74 cm) and Girl with a Jump Rope: Portrait of Delphine Legrand, 1876. Oil on canvas: 42 1/4 x 27 15/16 in. (107.3 x 71 cm)

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025) Cézanne's Madam Cézanne, 1888-1890. Oil on canvas: 36 1/2 × 28 3/4 in. (92.7 × 73 cm)

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025) Cézanne's Madam Cézanne with Her Hair Down, 1890. the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Oil on canvas: 24 3/8 × 20 1/8 in. (61.9 × 51.1 cm)

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025) Installation view of the final gallery of From Paris to Provence, showing (from left) Modigliani's Girl with a Polka-Dot Blouse (1919), Soutine's Woman in Blue (1919) and Modigliani's Portrait of the Red-Headed Woman (1918).

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025) Detail of portraits by Amadeo Modigliani and Chaim Soutine: Modigliani's Portrait of the Red-Headed Woman (1918). Oil on canvas: overall: 45 11/16 x 28 3/4 in. (116 x 73 cm); Modigliani's Girl with a Polka-Dot Blouse (1919). Oil on canvas: 45 1/2 x 28 3/4 in. (c 115.6 x 73 cm); Soutine's Woman in Blue (1919). Oil on canvas: 39 1/2 x 23 3/4 in. (100.3 x 60.3 cm)

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2025) Visitors to the Barnes Foundation, viewing works of art in the Main Room, north wall, of the museum.