Klimt Landscapes

Neue Galerie, Feb. 15- May 6, 2024

Reviewed by Ed Voves

Original Photography by Anne Lloyd

One of the most important reference works used to research Art Eyewitness reviews is The Oxford Dictionary of Art. Edited by Ian Chilvers. this Oxford volume is noteworthy for its succinct, incisive essays, providing essential data on major artists and art movements.

After visiting the sensational Klimt: Landscapes exhibition at the Neue Galerie in New York City, it was a sensible course of action to consult the Oxford Dictionary of Art in order to read their comments on Herr Klimt’s Landschaften.

The analysis of Klimt in the Oxford volume was certainly up to the high standards on other artists when I have used the book in the past. But there was one “down" note - and a.big one! There was no coverage devoted to Klimt’s landscape paintings in the entry for him.

This seeming omission could only have been caused by one of two reasons: (A) the Oxford Dictionary of Art discounted the importance of Klimt’s landscapes (B) the Neue Galerie, aware of Klimt’s popularity, promoted a minor facet of the Austrian artist’s paintings to a starring role in a major exhibition.

The correct answer is (C) none of the above.

Klimt's career trajectory experienced a radical break around the year 1900. On the one hand, these idyllic nature scenes, on view at the Neue Galerie until May 6, 2024, seem like a return to earlier, traditional work, but the revolutionary implications are quickly apparent the more you study them.

Klimt’s landscapes, painted during his summer vacations, were a special category of creative expression. These were works of exploration, not of the exactitude of the natural world, but rather of the spirit of nature and of Klimt’s own soul.

Each year from 1897 to 1917, Klimt spent part of the summer months painting in country resort areas. The annual Austrian holiday tradition, sometimes lasting as long as two months, was known as the Sommerfrische.

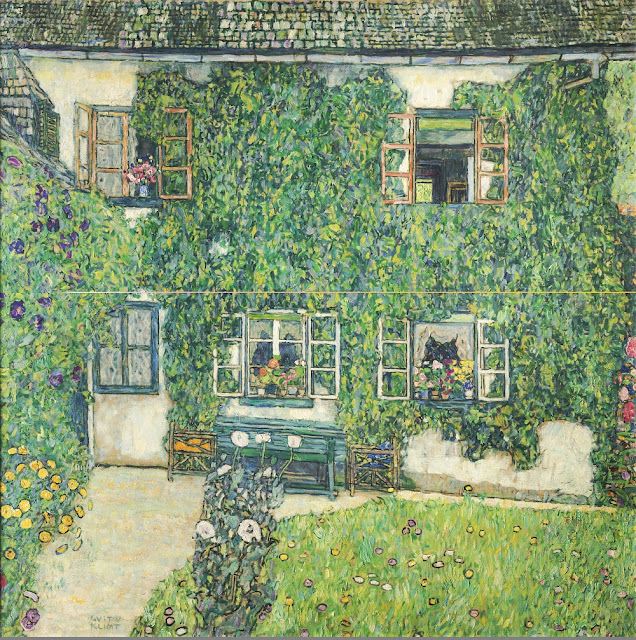

Klimt's summer paradise of choice was the Salzkammergut, the lake region of Austria. In particular, Klimt loved the area around the Attersee. This idyllic lake and the nearby villas, cozy cottages and the surrounding gardens provided the locales for Klimt's landscapes. Particular attractions were the imposing castle with accomadations for vacationers, Schloss Kammer, and the Forrester's House near the town of Weissenbach on the southern shore of Lake Attersee.

During his wartime summer visits, Klimt ventured deeper and deeper into the depths of the forest glades. The local people of Weissenbach started calling him the "woodland gnome." But scenery was not the only attraction for Klimt in the enchanted realm of the Salzkammergut. It was there that he could cultivate his remarkable association with a brilliant fashion designer named Emilie Flöge.

Emilie Flöge (1874-1952).was Klimt's sister-in-law. The exact parameters of their relationship have never been definitively established. They certainly were an unforgettable sight when together, Klimt looking like a magus in his painter's smock, Emilie wearing one of her trademark Reform Dresses. What can be said of them is that theirs was a close friendship and a creative collaboration based, in part, on a mutual love of nature.

The Neue Galerie has one of Emelie Flöge's Reform Dresses on view (center, below) in the exhibition. These dresses were intended to be stylish and comfortable, bucking the trend of restrictive women's apparel like corsets and hobble skirts. Indeed they were; but few sold.

The gallery photos also highlight one of the most notable features of Klimt Landscapes: the diversity of the exhibited works.

The exhibition has an excellent sampling of Klimt's landscape paintings, a half dozen. This is just enough to enable us to appreciate these wondrous "dreamscapes" which were true plein air works, painted outdoors.

An entire gallery of Klimt landscapes would have been almost hypnotic in its beauty. However, most of these works are the same shape and size (rectangular, approximately 39 x 39 inches, 101 x 101 cm), similar in color scheme and devoid of human presence.

I would be the last person in the world to say that, if you have seen one Klimt landscape, you have seen them all. However, the select number on view really is a case of "less is more." By limiting the number of landscapes, the curators of the exhibit enable us to focus more readily on those on view. Klimt's artistic technique and his stress on nature's propensity to "increase and multiply," on generation and growth, are emphatically underscored.

No better time of the year for depicting nature's bounty could be imagined than summer. No better place existed for the Sommerfrische than Lake Attersee.

Emma Bacher-Teschner Gustav Klimt in a row boat in front of the Villa Paulick, 1909

For Klimt, the Sommerfrische was partly a working vacation, along with plenty of hiking and rowing. In the early years covered by the Neue Galerie exhibit, Klimt brought design work for major commissions to the country villas or cottages he rented for his Sommerfrische. These included preliminary studies for the hugely controversial series of allegories for the University of Vienna (1894-1905) and the far more popularly-received mosaic for the Palais Stoclet in Brussels (1909-1911).

The landscape paintings on display in the Neue Gallerie exhibit all date from after 1900. Appearances to the contrary, these works have more in common with the erotically-charged allegories which shook the pillars of academe at the University of Vienna than they do with the rather tame evocations of Impressionism or Symbolism which Klimt painted prior to 1900.

Klimt was trained in theories and techniques of art rooted in Classical Antiquity and the Renaissance. His early work was well-received and not especially remarkable. Then, around the turn of the twentieth century, Klimt’s major theme in art shifted to the ideal of fecundity or the life force in nature. It goes without saying that this reproductive urge applied to human beings as well.

Life force was everywhere. It was a philosophical tenet of major importance throughout Europe at this time. In the Germanic-speaking lands, lebenskraft, and elan vital in France, was promulgated with such conviction that it carried through to almost every facet of life, from the idea of progress in society to militaristic assertions that the “will to victory” would ensure battlefield success.

Klimt envisioned life force in earthy, sensual terms. Then, in the idyllic surroundings of the Attersee, he evoked this vision en plein air, done entirely without preliminary sketches. Lebenscraft guided his brush.

Klimt's The Large Poplar is the earliest of the landscapes on view, dating to 1900. Klimt was a great admirer of Claude Monet but these towering trees are nothing like the series of poplars bordering the Epte River as painted by the Impressionist master in 1891.

In certain respects, there is a greater similarity to the cypress trees which figured so often in another of Klimt's favorites, Vincent van Gogh. Yet, Klimt did not get the opportunity to study Van Gogh until 1903 when Klimt's own Vienna Secession group mounted an exhibition of modernist works with six Van Gogh paintings on view.

The 1903 exhibition was a momentous occasion for Klimt. A Van Gogh Sunflowers was one of the selected works. It made a big impact on Klimt who painted his own rendition in a 1907 painting, which reappeared as a print in his collected works, Das Werk von Gustav Klimt (1918).

But all this was three years after the fact, as far as exerting any influence on Large Poplar and Klimt's "radical" transformation of 1900.

Where then did Klimt, who had little formal training in landscape painting, go for insights and inspiration as he sought to evoke the scenic locales of his Sommerfrisch? The influence of Georges Seurat and the Neo-Impressionist school are obvious candidates as exemplars of the myriad of tiny dots which filled Klimt's canvasses. But, however aware Klimt was of the scientific principles underlying Pointillism, this was not his guiding star.

The bounty, abundance, the sheer multiplicity of nature was the source of Klimt's fantastical vision of the Sommerfrische world around him.

Millions upon millions of grains of pollen, seedlings, blossoms, flowers opening their petals to the sun and glistening green leaves appear in Klimt’s landscapes. Captured in dense patterns of dots and speckles of oil paint and displayed on the walls of the Neue Galerie, these images testify to the Austrian artist's insight into the natural world.

As Anne and I soon discovered, confirmation of Klimt's approach to nature beckoned just a little beyond the museum's doors.

Anne and I departed from Klimt Landscapes, greatly impressed by this latest triumph for the Neue Gallerie.

After leaving the Neue Galerie, we decided to spend a few minutes in Central Park taking a couple of pictures. It was then that we saw what Klimt envisioned and painted: life force, lebenskraft.

All this happened on a beautiful Monday in late April. There was some kind of magic going on, in the Neue Galerie's Klimt Landscapes exhibition and in Central Park.

It was a little early, as least by the calendar, for Sommerfrisch. But the "magic" was right on time for lebenskraft.

Text: Copyright of Ed Voves, all rights reserved; original photography, copyright of Anne Lloyd

Introductory Image: Moriz Nahr (Austrian, 1859-1945) Gustav Klimt in the garden of his studio at Josefstädter Strasse 21, April/May, 1911 (Detail). Vintage gelatin silver print Neue Galerie New York.

Anne Schlechter Photo (2024) Installation view of Klimt Landscapes, Neue Galerie. Photo courtesy of Neue Galerie.

Gustav Klimt (Austrian,1862-1918) Park at Kammer Castle, 1909. Oil on canvas. Neue Galerie New York. Part of the collection of Estée Lauder and made available through the generosity of Estée Lauder.

Gustav Klimt (Austrian,1862-1918) Forester’s House in Weissenbach II (Garden), 1914.

Heinrich Bohler, Gustav Klimt and Emilie Flöge,

Kammerl/Attersee, 1909. Heliogravure, Neue Galerie New York.

Anne Schlechter Photo (2024) Installation view of Klimt Landscapes, Photo courtesy of Neue Galerie

Anne Schlechter Photo (2024) Installation view of Klimt Landscapes, showing prints by Gustav Klimt & Wiener Werkstatte jewelry by Kolomon Moser & Josef Hoffmann. Photo courtesy of Neue Galerie

Emma Bacher-Teschner,(Nee Paulick) (Austrian,1867-1948) Gustav Klimt in a row boat in front of the Villa Paulick,Seewalchen/Attersee, 1909. Vintage gelatin silver print. Neue Galerie New York.

Gustav Klimt (Austrian,1862-1918) Two Girl’s with Oleander, ca. 1890-92. Oil on canvas. Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, CT. The Douglas Tracy Smith and Dorothy Potter Smith Fund and The Ella Gallup Sumner and Mary Catlin Sumner Collection Fund.

Gustav Klimt (Austrian,1862-1918) The Large Poplar, I, 1900.

Gustav Klimt (Austrian, 1862-1918) Reproduction of Sunflower, 1907-08. Collotype with gold intaglio Printer: K. K. Hof- und Staatsdruckerei First Publisher: H. O. Miethke, 1908-14 Reissued: Hugo Heller Kunstverlag, 1918 Neue Galerie New York.

Gustav Klimt (Austrian, 1862-1918) Pear Tree (Pear

Trees), 1903 (later reworked) Oil and casein on canvas. Harvard Art Museums/Busch-Reisinger Museum, Gift of Otto Kallir.

Anne Lloyd,Photo (2024) View of Central Park, New York City, April 22, 2024.

Anne Schlechter Photo (2024) Staircase

& Entrance to Klimt Landscapes, Neue Galerie.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024) Spring Blossoms & Foliage, Central Park, April 22, 2024

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024) A "Klimt Landscape" in Central Park.

.jpg)

,%201921.jpg)