Neo-Impressionism and the Dream of Realities:

Painting, Poetry, Music

September 27, 2014, through January 11, 2015.

Reviewed by Ed Voves

In May 1886, the Impressionists held their eighth and last joint exhibition. Some of the great pioneers of Impressionism - Claude Monet, Pierre Renoir and Alfred Sisley - did not participate. But two young innovators, Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, did exhibit paintings.

Seurat displayed more than several new works of art. He unveiled a revolutionary technique - Pointillism. With this juxtaposition of thousands of minute dots of color on his canvas, Seurat created a sensation. His luminous A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte marked the beginning of a new age of art, a new way of seeing.

The ensuing artistic revolution, which quickly received the title of Neo-Impressionism, is the subject of a splendid exhibition at the Phillips Collection in Washington D.C. Neo-Impressionism and the Dream of Realities: Painting, Poetry, Music traces the transformation of Seurat's meticulous configurations of colored dots into a major cultural event in the rise of Modernism.

Two key features of the exhibition need to be quickly addressed. A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte is not on view at the Phillips collection. This vast masterpiece, the pride of the Art Institute of Chicago, is in too delicate condition to travel on loan. The second noteworthy point is that the outstanding array of paintings on view in the Phillips exhibition illustrate a theme which is not dependent on any one work of art, even one of the stature of La Grande Jatte.

Art scholars usually focus upon Neo-Impressionism's adaptation of scientific color theory to art. Curator Cornelia Homberg, however, has shifted the focus of Neo-Impressionism to its relationship to Symbolism, the great cultural movement in Europe during the 1880's and 1890's.

Symbolism aimed to discover and represent the inner wisdom of humanity. Henry van de Velde, the Belgian painter who played a major role in the rise of Art Nouveau, affirmed that this was the parallel goal of Neo-Impressionism, as well. Van de Velde wrote in 1890, that the Neo-Impressionists aimed "to establish the Dream of realities ... to strive for the pursuit of the Intangible and meditate - in silence - to inscribe the mysterious Meaning."

Seurat's role was, of course, pivotal to the birth of Neo-impressionism. His radiant Seascape at Port-en-Bessin, Normandy, painted the same year as La Grande Jatte, readily enables visitors to the Phillips exhibition to grasp the nature of pointillist technique.

Georges Seurat, Seascape at Port-en-Bessin, Normandy, 1888.

Naturalism is another matter. Seurat's Port-en-Bessin is very different from one of Monet's views of the famous natural arch at Etretat, also on the coast of Normandy. Monet painted scenes of Etretat at different times of the day to reflect actual moments of reality. Seurat's Port-en-Bessin has a stylized, almost childlike feel to it. The scene of fierce fighting during the 1944 D-Day landings, Port-en-Bessin is subdivided into three clearly demarcated zones, land, sea and sky, like a medieval depiction of the realms of God's creation.

Seurat also created remarkable theater-inspired works, which appear in the exhibition at the Phillips. Woman Singing in a Café Chantant, 1887, and At the Gaîté Rochechouart (Caféconcert), c. 1887–88, show a direct kinship with La Grande Jatte in the positioning of the figures. These distinctive works, which have the tone and quality of photographs, demonstrate that Seurat embraced the culture as well as the science of his era.

Georges Seurat, Woman Singing in a Café Chantant, 1887.

Just as Neo-impressionism was gaining momentum, Seurat contracted diptheria and died with shocking suddeness in 1891. That year also saw the premature death of Albert Dubois-Pillet, a French army officer who was a gifted Neo-Impressionist artist. A little before these calamities had come the rejection of Pointillism by Camille Pissarro after several years of experimentation.

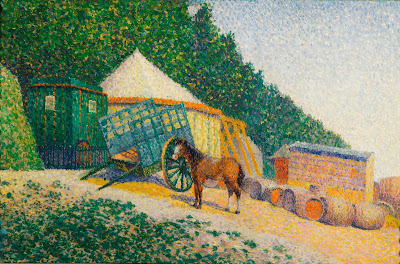

Albert Dubois-Pillet, Little Circus Camp, n.d.

These tragic events placed the burden of leadership of the Neo-Impressionist movement upon the shoulders of Seurat's devoted friend, Paul Signac. It was Signac who wrote the key text, From Delacroix to Neo-Impressionism, published in 1899. In his book, Signac asserted that Neo-Impressionist art "thanks to its constant observation of contrast, its rational composition, and its aesthetic language of colors, includes a general harmony and a moral harmony."

Seurat labored for two years, 1884 to 1886, painting La Grande Jatte. While it is true that he made many preparatory studies for this landmark painting, Seurat's approach was more of a musical composer than a transcriber of nature. He carefully placed the Sunday afternoon pleasure seekers on his landscape as a composer arranges the notes of his or her symphony, creating "a general harmony and a moral harmony."

When Signac began to paint a great series of seascapes, he added the names of musical movements to the titles of many of his paintings. This was not a culture-conscious ploy, but rather an accurate visual reflection of musical cadence.

Paul Signac, Setting Sun. Sardine Fishing. Adagio. Opus 221, 1891.

Look at Signac's Setting Sun. Sardine Fishing. Adagio. Opus 221 from the series The Sea, The Boats, Concarneau. The armada of small fishing boats and the gentle, rippling movement of the sea perfectly evoke the slow, graceful tempo of an adagio in music. Signac, an experienced sailor with his own yacht, skillfully united nature and art, music and painting in this brilliant work.

Signac was a charismatic figure. Under his leadership, the Neo-Impressionism movement rallied. Signac was also left-wing in his politics and was sympathetic to the Anarchist movement. The Metropolitan Museum of Art has an 1886 sketch by Signac, The Gas Tanks at Clichy,which shows an Anarchist slogan, "Death to the Cops" scrawled on the wall of a blighted area of Paris. Signac's painting, based on this sketch, has gone missing.

Signac was joined by another artist with a radical political background, Maximilien Luce. Arrested by the French police in 1894 on suspicion of involvement in the assassination of President Sadi Carnot, Luce was later acquitted. Art critics at the time claimed that Luce's paintings were steeped in political ideology. But his beautiful depiction of Paris by night, Le Louvre et le Pont du Carrousel la Nuit, is typical of the lyrical nature of much of his work.

Maximilien Luce, The Louvre at the Pont du Carrousel at Night, 1890.

Signac also found ready allies in the Belgian avant-garde group, Les XX or "The Twenty." These gifted, forward-looking Belgians had in fact sought to establish ties with Seurat and Signac from the very beginning. Emil Verhaeren, one of the leading art critics in Belgium, visited the Eighth Impressionist exhibition and sent word about La Grande Jatte back to Brussels.

Octave Maus, the secretary of Les XX, did not need much convincing. Maus called Seurat “the Messiah of a new art.” A year after the last Impressionist exhibit, Seurat was invited to exhibit with the Belgian group and Signac followed in 1888.

Willy Finch, Georges Lemmen and Théo van Rysselberghe responded with alacrity to seeing La Grande Jatte. They changed their personal painting styles to embrace Pointillism but were ambitious to make their own mark. Lemmen and van Rysselberghe, talented portrait painters, made a concerted effort to adapt Pointillism to capturing the outward likeness and the inner being of those around them.

Georges Lemmen, Portrait of Jan Toorop, 1886.

Lemmen's Portrait of Jan Toorop was one of the first Neo-Impressionist portraits. The subject was a Dutch Neo-Impressionist whose vivid pointillist landscape Broek in Waterland (1889) is displayed in the exhibit. Lemmen captured the prosaic pipe-smoking reality of daily life, while evoking the ineffable mystery that is inside each person.

The Phillips exhibition also displays van Rysselberghe's Portrait of Irma Sethe. This magnificent full-length portrait not only depicts a young woman absorbed in playing a violin but it brilliantly evokes the process of listening to music in the partly-obscured figure in the background.

Despite these accomplishments, Pointillism did not lend itself to portraiture. By 1895, Lemmen moved to a style that was more in line with Impressionism. Van Rysselberghe persisted with Pointillism for nearly a decade more. A very close friend of Signac, he joined the circle of painters that based themselves around Signac's home at St. Tropez, still a minor fishing village on the Mediterranean coast. Eventually, van Rysselberghe relegated Pointillism to details of his work but no longer focused upon it as his preferred style.

Studying van Rysselberghe's paintings, especially the portraits, one gets the sense that he was drawn to Pointillism because this demanding and difficult style was a bracing challenge to his abundant talents.

Theo van Rysselberghe, Canal in Flanders (Gloomy Weather), 1894.

In his Canal in Flanders (Gloomy Weather), painted in 1894, van Rysselberghe contradicted the theories on the use of complementary colors that were at the very heart of Neo-Impressionist doctrine. Where Signac had produced a text-book example of balancing dots of blue with gold and orange in his scene of fishing boats discussed above, van Rysselberghe used tones of blue and green, non-complementary colors. Yet, Canal in Flanders is an entirely successful example of Pointillism.

Signac succeeded in establishing a "Studio of the South" at St. Tropez such as Vincent Van Gogh had tried and failed to create at Arles a few years before. Van Rysselberghe, Luce and another close friend, Henri-Edmond Cross, joined him on the Côte d'Azur, painting idyllic scenes of life lived in harmony with nature.

Henri-Edmond Cross, Beach at Cabasson (Baigne-Cul), 1891-92.

Beach at Cabasson (Baigne-Cul), painted by Cross, is an almost perfect embodiment of later Neo-Impressionism at its best. The painting also illustrates the appeal of the pastoral tradition in nineteenth century Europe, beset as it was by the baneful consequences of industrialism. The Arcadia of these innocent children, enjoying the pleasures of a golden afternoon by the sea, represented a world that was swiftly passing away.

By the turn of the twentieth century, Neo-Impressionism's day was nearly done. But before it yielded center stage to new artistic visions, the color-dappled oeuvre of Seurat and Signac produced one more surprise.

In 1904, a struggling artist from the north of France came down to St. Tropez at Signac's invitation. Although he would only paint one great work in the pointillist style, this painting triggered the artistic breakthrough that led in due course to the "Shock of the New" art of the twentieth century.

This painting, which Signac bought, now hangs in the Musée d'Orsay. It is entitled Luxe, Calme et Volupté and the man who painted it was named Henri Matisse.

Text: Copyright of Ed Voves, all rights reserved

Images Courtesy of the Phillips Collection, Washington. D.C.

Introductory Image: Paul Signac, Place des Lices, St. Tropez, 1893. Oil on canvas, 25 3/4 x 32 1/4 in. Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh. Acquired through the generosity of the Sarah Mellon Scaife Family. Photograph © 2014 Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh

Georges Seurat, Seascape at Port-en-Bessin, Normandy, 1888. Oil on canvas, 25 1/2 x 32 in. National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of the W. Averell Harriman Foundation in memory of Marie N. Harriman, 1972.9.21

Georges Seurat, Woman Singing in a Café Chantant, 1887. Black and blue chalk, white and

pink gouache, pencil and brown ink on paper 11 5/8 x 8 7/8 in. Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

Albert Dubois-Pillet, Little Circus Camp, n.d. Oil on canvas, 10 3/4 x 16 1/8 in. Acquired 1927. The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC

Paul Signac, Setting Sun. Sardine Fishing. Adagio. Opus 221 from the series The Sea, The Boats, Concarneau, 1891. Oil on canvas, 25 5/8 x 31 7/8 in. Mrs. John Hay Whitney Bequest. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2014 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Maximilien Luce, The Louvre at the Pont du Carrousel at Night, 1890. Oil on canvas, 25 x 32 in. Private Collection

Georges Lemmen, Portrait of Jan Toorop, 1886. Chalk on paper, 23 x 17 in. Collection Museum de Fundatie, Heino/Wijhe en Zwolle, The Netherlands

Theo van Rysselberghe, Canal in Flanders (Gloomy Weather), 1894. Oil on canvas, 23 3/4 x 31 1/2 in. Private collection

Henri-Edmond Cross, Beach at Cabasson (Baigne-Cul), 1891-92. Oil on canvas, 25 3/4 x 36 3/8 in. The Art Institute of Chicago, L. L. and A. S. Coburn, and Bette and Neison Harris funds; Charles H. and Mary F. S. Worcester Collection; through prior acquisition of the Kate L. Brewster Collection

Thank you for a wonderful post. It's been shared with Phillips Collection staff and volunteers (of which I am one).

ReplyDeleteNice Blog...

ReplyDeleteThanks for sharing this informative blog. There are various Neo impressionist artists and painters who came across after the neo impressionism movement. To know more about impressionism visit Leighton Fine Art Ltd.