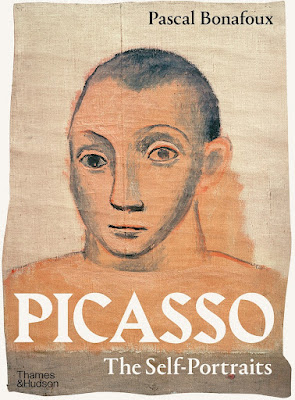

Picasso: the Self-Portraits

By Pascal Bonafoux

Thames & Hudson/$45/223 pages

Reviewed by Ed Voves

Often times, when a great writer, actor or artist of advanced age dies, the reaction is a bemused exclamation, "I didn't know he (or she) was still alive."

When Pablo Picasso died a half century ago, on April 8, 1973, that was not the response. No one thought of Picasso in the past tense, but rather with shock that he could die.

Yes, Picasso had lived a very long time, 1881-1973. Yes, many of his best works were already on museum walls years before his passing. Picasso, however, was such a legendary figure, an artist of genius caliber, that it was hard to conceive of the art world without him.

Fifty years on, art historians are still grappling with the legacy of Picasso. Museums around the world have announced exhibitions to mark the anniversary of his death - and his continuing importance. While these upcoming exhibits will doubtless provide new insights, museum curators are already facing stiff-competition from an impressive new book, Picasso: the Self-Portraits, written by the French art historian, Pascal Bonafoux.

There are a number of surprising aspects to this outstanding book. Perhaps the most glaring one is the fact that this is the first systematic study of Picasso's self-portraits. Considering the exhaustive treatment of Picasso's oeuvre, it is a bit perplexing that this trove of revelatory art has been little regarded by scholars, at least as a body of work - and an extensive one at that.

Picasso: the Self-Portraits examines 170 paintings, drawings and photos. Beginning with an 1894 drawing of himself, aged thirteen, Picasso continued to record - and in some cases, disguise - his features up until a few months before he died.

Most of these self-portraits, however, were created before 1918. In November of that year, Picasso heard the shocking news that his great friend, Guillaume Apollinaire, had just died during the Influenza pandemic. According to legend, Picasso was shaving when the message arrived and could not bear looking into a mirror after that terrible moment. Doing so reminded him of the painful passing of Apollinaire - and of his own mortality.

The second surprise factor is the curiously "old-fashion" look to the present volume. The book opens with the text, eighty-plus pages of solid print, en bloc. Then come the pictures, treated with superb fidelity whether color, sepia or black and white, but lacking explanatory captions. Given that the publisher is Thames and Hudson, who practically invented the process of closely integrating pictures with text in art books, this arrangement did come as a bit of shock when I first leafed through the pages.

Any doubts about Picasso: the Self-Portraits vanished by the time I finished reading the first couple of paragraphs. It was a master-stroke to use Bonafoux's brilliant narrative to engage the reader's imagination, followed by the pictures. Bonafoux is an exceptional writer, a French intellectual whose scholarship is tempered with warm human empathy and philosophic insight.

In many ways, Bonafoux's text is a meditation on life, Picasso's and ours. Quoting a remark by Picasso that "a painting only lives through the person looking at it," Bonafoux invites us to join in this silent dialog.

Alone. I am alone before Picasso's self-portraits. You are alone before these same self-portraits... And perhaps that is the purpose of a self-portrait, to make us examine our own solitude.

So let the words and the images of Picasso: the Self-Portraits speak for themselves without constant referring back and forth. The best way to use this intriguing book is to savor the text and images as complementary essays.

Bonafoux begins his narrative by relating how he met Picasso's widow, Jacqueline, at a dinner party. Bonafoux's specialty in art scholarship is the study of self-portraits from the Renaissance to the contemporary world.

During their discussion about art, Jacqueline Picasso asked if Bonafoux had referred to Picasso's self-portraits in his research. Bonafoux replied by mentioning the mirror incident, which the photographer Brassai had related. Jacqueline Picasso contradicted Brassai's account, telling Bonafoux that Picasso had continued to create self-portraits after 1918. This exchange launched Bonafoux on a forty-year exploration of how Picasso came to depict himself in paintings and drawings over the course of his life.

Later, Jacqueline showed Bonafoux a self-portrait by Picasso, (above) dated to 1959. The 1959 date referred to the occasion when Picasso presented it to her. The drawing was actually created in 1917.

The Self-Portrait is exceptionally crisp and well-delineated, worthy of the classical style of French drawing, especially the portrait sketches of Jean Auguste Ingres (1780-1867). Picasso executed several more in this manner, but almost all before the end of World War I. The self-portraits he created in the years that followed the war were few in number and very varied in composition. Apparently, there was an element of truth in both what Brassai and Jacqueline Picasso had stated.

Bonafoux discounts a shattering event like Apollinaire's death (which was certainly upsetting to the artist) as having any real effect on Picasso's production of self-portraits.

For Picasso, self-portraits were more documents of experimentation than documentation. That is why most of the self-portraits were created when Picasso was very young. He was finding his way in the world, especially when he made the decision to settle in France, despite the vibrant culture of Barcelona and the fellow-artists whose friendship he celebrated in a poster for the fabled cafe, Els Quatre Gats.

The self-portraits of Picasso's early years how him in many guises: dressed as a top-hatted Parisian boulevardier (despite being nearly destitute); sporting a mustache, making him look much older than his age in 1901; even a rather silly pose, wearing the crown of an Egyptian Pharaoh, in a composite drawing.

Pablo Picasso, Self-portrait as a Pharaoh, 1903-4

Many of these early self-portraits would be of little interest today except that Picasso had created them. But create them he did, as he investigated the life around him and within, with abundant explorations of sexuality as evidenced by the accompanying nude sketches on Self-portrait as a Pharaoh.

Bonafoux notes that a constant factor in Picasso's life was his devotion, indeed obsession, to change. From early on, he set himself to oppose the established conventions of art, summed-up under the disparaging term, style. This leads Bonafoux to the "paradoxical conclusion" that "it is the very changeability of Picasso's work that makes it endure."

"Perhaps," Bonafoux muses, "we should therefore view Picasso's self-portraits as symbols of these changes that look like him... When he paints himself, he is not so much seeking to represent Picasso as he is seeking to be a Picasso."

If many of the early self-portraits merely reflect the "changes that look like him," several were major, monumental likenesses. The haunting, 1901 Blue Period Self-Portrait and the 1906 "Iberian" Self-Portrait from the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art are works which evoke Picasso's moods and interests at the time he painted himself on these canvases. But both works probe deeply below surface details, into Picasso's soul and psyche. Together these self-portraits forecast the mature Picasso's role as the Magus of Modern Art.

None of the self-portraits which Picasso created during the inter-war years, 1918-1939, or the period following the Second World War, approached these early works in skill or interest. Some are technically significant, others little more than sketches.

This takes us back to the "mirror image" question. This time, we can safely say that Picasso now had little need to represent himself. He was now painting and drawing "Picasso" in each and every one of his works. The painter of Guernica had little need to limit himself to autobiography.

Only very late in life, when Picasso was indeed confronting his mortality, did he return to a serious focus on self-portraits. In 1972, only months before he died, Picasso created several skull-like depictions of himself, looking like apparitions from beyond the grave. These leave little doubt as to where his thoughts were directed.

In one of the most poignant reflections in his compelling narrative, Bonafoux affirms that the real, lasting value of self-portraiture is the way it encourages, indeed insists, that artists remain true to themselves:

The only model who is always available to a painter, the only model who they can be sure will never recoil, offended or disappointed, on seeing the final portrait, is themselves. Their own image is what artists have always measured themselves against, time and again, to establish their visual identity.

Delete the words "painter" or "artist' from these wise words and forget about Pablo Picasso for the moment. Apply Pascal Bonafoux's sage reflection to ourselves. This I think will make for a very telling experience, the next time we look into a mirror.

***

Text: Copyright of Ed Voves, all rights reserved. Original photography by Anne Lloyd, all rights reserved.

Images of works by Pablo Picasso, courtesy of Thames and Hudson

Introductory Image: Cover art of Picasso: the Self-Portraits, by Pascal Bonafoux, courtesy of Thames and Hudson, 2023.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2020) Pablo Picasso's Self-Portrait, 1906. Oil on canvas: 36 3/16 inches x 28 7/8 inches. Philadelphia Museum of Art. (Photo by Anne Lloyd, 2020)

Pablo Picasso, Picasso with a Woman, 1901, ink and watercolor on paper, 17.3 x 13 cm. Private collection. © Succession Picasso 2022

Pablo Picasso, Profile, 1901, ink on paper, 21 x 13 cm. Private collection. © Succession Picasso 2022

Pablo Picasso, Self-portrait as a Pharaoh, 1903-4, Chinese ink and colored pencils on paper, 26 x 36 cm. Private collection. © Succession Picasso 2022

No comments:

Post a Comment