Graphic Passion: Matisse and the Book Arts

Morgan Library and Museum

October 30, 2015 through January 18, 2016

Reviewed by Ed Voves

Vive la différence! To many, these words embody the passionate commitment of the French people to individualism, to the unique differences that define the character of each person.

For Henri Matisse, the meaning of " la différence" had an added significance. Embracing "la différence" enables an artist to depict a character, a scene or a theme in a way that represents a personal conception of reality. While doing so, the artist may ignore or contradict the "here and now" details of superficial existence - and yet achieve a vision of transcendence.

"Exactitude," Matisse famously proclaimed, "is not truth."

Pierre Matisse, Henri Matisse in the Bois de Boulogne (ca. 1931–1932)

The Morgan Library and Museum in New York City is currently displaying an exhibit of Matisse's unconventional book illustrations. Graphic Passion: Matisse and the Book Arts is the second Matisse exhibit of note to appear during 2015 in New York City. Henri Matisse: The Cut-Outs was mounted by MOMA to huge acclaim earlier in the year. Graphic Passion is a smaller, more focused exhibit but equally brilliant.

Most of the works on view in Graphic Passion were collected by an art loving couple, Frances and Michael Baylson, who donated their collection to the Morgan in 2010.

Matisse possessed the singular ability to create images that often had only a thin, barely recognizable connection to the original source. Graphic Passion surveys the illustrations which Matisse created to grace the pages of limited edition books of a type called livre d'artiste.

Henri Matisse, Dessins: Thèmes et variations, 1943

Other great artists besides Matisse illustrated livre d'artiste. Picasso, Braque, Miró and other "old masters" of Modernism created memorable images to complement the literary content of these books.

"To complement" is indeed the appropriate verb to use when describing the artistic process involved in a livre d'artiste. As the name suggests, these books recognized the primacy of the artist. In a livre d'artiste, the text takes on a secondary role to the picture.

In the case of his art work for Pasiphaé, Chant de Minos, Matisse created images in the traditional mode of book illustration. For this livre d'artiste, published in 1944, Matisse closely correlated his pictures with the poems of Henri de Montherlant. These poems rework the story from Greek mythology of the queen, cursed by the gods, who gives birth to the dreaded Minotaur. Matisse used a form of engraving on linoleum to produce white lined images on a black background. This worked brilliantly to evoke the eroticism and horror of this ancient tale.

Henri Matisse, Pasiphaé, Chant de Minos, 1944

Matisse seldom repeated his success with Pasiphaé of closely matching image and text. The Morgan exhibition commentary - always enlightening, but especially well-done for Graphic Passion - affirms that for the most part Matisse regarded his livre d'artiste illustrations as independent works of art.

Usually ... Matisse preferred to maintain a respectful distance from the text, which he believed should not have to be “completed” by his visual interpretation. He thought that illustration should be decorative in the best sense of the word, a separate and “parallel” form of artistic expression acknowledging and complementing the achievements of the author.

When obscenity charges were withdrawn in U.S. courts against Ulysses by James Joyce, Matisse signed a contract in 1934 to illustrate an expensive American edition of the book. Matisse kept such a "respectful distance" from the text that many were perplexed, Joyce included, as to the effect on readers.

One of the Ulysses pictures, on view in the Morgan exhibit, illustrates the serendipitous route which Matisse followed to create his images. Matisse chose a female circus performer he had witnessed at the Concert Mayol in Paris - who walked down a flight of steps on her hands - for his model in the brothel scene of Joyce's Ulysses.

Henri Matisse, preliminary study of Circe, 1934

Joyce had earlier agreed to Matisse evoking the Odyssey in his drawings rather than directly representing episodes in Ulysses. Joyce grasped Matisse's idea, as the scene representing the alluring Circe is close enough to what transpires in a brothel.

The American publisher of the new edition, William Macy, however, was upset. With Joyce's text difficult enough to grasp, he felt that the pictures should make it easier, not harder to comprehend the book.

Matisse would not change his approach, even when Macy initially withheld payment.

Vive la différence!

Matisse worked on over fifty book design projects between 1912 and 1952. A number of these illustrated the works of writers whom Matisse cherished, especially poets like Stéphane Mallarmé and Charles Baudelaire.

A devoted reader of classic French poetry, Matisse was involved in a major publishing venture to illustrate Baudelaire’s Les fleurs du mal. One of the poems in Les fleurs du mal contained the line, “Luxe, calme et volupté" (Luxury, peace, and pleasure), that provided the title for the famous 1904 painting by Matisse.

This livre d'artiste, pairing Baudelaire and Matisse, should have been a triumph easily brought to success. Instead, it was a trial from the start.

Originally planned before the Second World War, the project suffered from repeated miscues and mishaps, mostly related to the war. Matisse was unable to start working in earnest until his beloved daughter Marguerite, arrested by the Gestapo, had been liberated in 1944.

Matisse eventually matched spare portrait lithographs with a selection of Baudelaire's poems from Les fleurs du mal. The portraits are mostly of youthful women, Matisse's models, including his devoted assistant, Lydia Delectorskaya, a refugee from Russia. Despite the current of eroticism that flows through the poems of Baudelaire, Matisse's young women radiate simplicity and beauty.

Henri Matisse, rejected cover design for Les fleurs du mal, 1946

For the cover illustration, to evoke the decadence and evil of the title of Baudelaire’s anthology, Matisse briefly considered an image of an octopus. Before it was discovered to be a shy and harmless creature (to humans) the octopus was viewed as a sinister menace. But Matisse changed his mind about the sea creature, substituting an amorphic, abstract design.

Neither youthful, unassuming women nor an octopus are characteristic elements of Les fleurs du mal. What was Matisse aiming at with these images? Perhaps the date of publication is a key to the mystery - 1947.

Matisse created these images for a new edition of Les fleurs du mal in the aftermath of Auschwitz and Hiroshima. How can an artist grapple with the crushing reality of evil or evoke ideals of beauty in the wake of such horrors?

"I have always thought," Matisse wrote "that a large part of a painting's beauty derives from the artist's combat with his own limited means of expression."

With this quote we have an answer for the difficult-to-fathom nature of the often mysterious works of art in the Morgan exhibit. Matisse aimed to overcome "his own limited means of expression" to summon the spirit, if not always the outward form, of his subjects.

The same year of Matisse's illustrations of Les fleurs du mal, 1947, also saw the publication of Jazz. This is the greatest Matisse livre d'artiste and one of the greatest of the genre.

The origin of Jazz can be traced to 1941 when Matisse was recuperating from surgery for abdominal cancer in 1941. Confined to his bed, Matisse began to "paint with scissors." He cut-out delicate designs from colored paper, a skill that may be traced back to the scissors-craft of his cloth-making ancestors in the north of France. These images were pinned to a paper background (or sometimes the walls of Matisse's room) to form works of art of primal intensity.

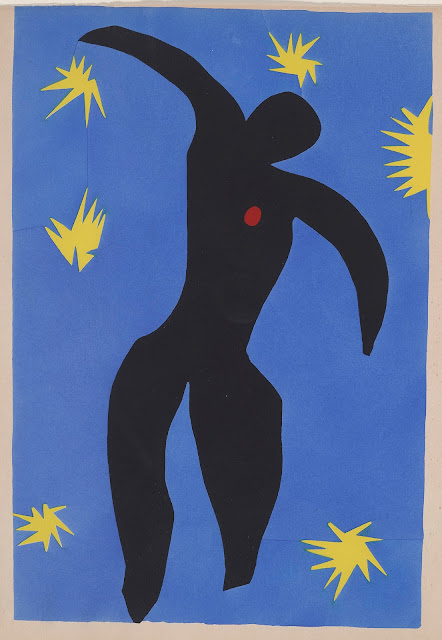

It was a high-point for me to go the recent MOMA exhibition and view Matisse's The Fall of Icarus (1943) with the pins still inserted. It was no less inspirational to see the prints that were made of Icarus, first in 1945 for the French art magazine, Verve, and then as Plate VIII for Jazz.

Henri Matisse, Icarus, plate VIII, Jazz, 1947

Icarus may seem an odd choice to be included in Jazz. As we will shortly see, some of the images Matisse created for Jazz are evocations of joy and exhilaration. Matisse's Icarus in the 1943 cut-out and the 1947 pochoir or fine-grade stencil print is another matter.

Matisse's Icarus is surrounded by bursting flashes of light, reminiscent of the "star shells" used to illuminate the battlefields of World War I. Icarus is not merely falling, wingless as in the ancient myth by flying too near the sun. He is reeling like a soldier hit by bullet. Here there is no sun melting his wings, just jagged gashes of flame which reveal his death throws.

Henri Matisse, The Tobaggan, plate XX, Jazz, 1947

It's more than a bit disconcerting to look at the female figure sliding, head over heels in The Tobaggan, Plate XX of Jazz, and then glance back to the dying fall of Icarus. But the more time that one spends studying Jazz, the realization grows that pleasure and pain are balanced in almost equal measure.

Jazz is often said to have a circus theme. If so, it's a tight wire act without a safety net for our emotions. One of the most lyrical plates in Jazz shows a pair of jaunty circus horses pulling a colorfully decorated cart. It is not a circus wagon bringing performers to the Big Top. Rather, Plate X shows a hearse. The high-stepping circus horses are carrying the clown Pierrot to his grave.

The time span covered by Graphic Passion runs from 1912 to 1952. Yet, it is the last decade that really counts.

The 1940's were a tough time to be a Frenchman or an artist, or just a person of conscience and vision. Matisse was all of these, as well as being elderly and in poor health. Taken in unison, these factors did not defeat him. Instead, Matisse rose to the challenge. He embraced the role of champion of civilization at a time when it was not certain it would survive the Nazi war on culture.

In 1942, having recuperated somewhat from his cancer operation, Matisse selected the poems of the French poet of the late Middle Ages, Charles d’Orleans (1394-1465) as the subject of a livre d'artiste.

Henri Matisse, Poèmes de Charles d’Orléans, 1950

A great aristocrat with links to the royal family of France, Charles d’Orleans found that his blue blood and gilded armor did not protect him from the vicissitudes of life during the Hundred Years War. In 1415, he was pulled, dazed and battered, from under a pile of corpses at the Battle of Agincourt. He spent the next quarter of a century as a prisoner in England during which he wrote his immortal poetry.

Matisse was moved by the life and poetry of Charles d’Orleans.The experience of a poet who had triumphed over the horrors of war in the fifteenth century greatly appealed to an artist who did likewise in the twentieth century. Matisse not only did illustrations for Poèmes de Charles d’Orleans but copied the poems in a flowing calligraphic script that was reproduced by his publishers, Tériade, when this remarkable book was published in 1950.

Matisse had but one decade of life left to him as he labored on Poèmes de Charles d’Orleans, Jazz and Les fleurs du mal. Working against the hourglass of mortality, Matisse summoned a lifetime of experience to create his livre d'artiste images.

Thanks to this wonderful exhibition at the Morgan Library and Museum, we are privileged to see how the aging Matisse created illustrations of profound beauty and power. Graphic Passion leaves little doubt that Matisse's book images can truly be described as being immortal - if any work of art can ever be so.

***

Text: Copyright of Ed Voves, all rights reserved

Images courtesy of the Morgan Library and Museum, New York City

Introductory Image:

Henri Matisse (1869–1954), Circus, pochoir, plate II in Jazz (1947). Courtesy of Frances and Michael Baylson © 2015 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.Photography by Graham S. Haber, 2015.

Pierre Matisse (1900–1989), photograph of Henri Matisse in the Bois de Boulogne (ca. 1931–1932). Gift of the Pierre and Tana Matisse Foundation, 1997, The Morgan Library & Museum. © 2015 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Henri Matisse (1869–1954), Dessins: Thèmes et variations ... précédés de “Matisse-en-France” par Aragon. Paris: Martin Fabiani, 1943. Frances and Michael Baylson Collection, The Morgan Library & Museum. © 2015 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photography by Graham S. Haber, 2015.

Henri Matisse (1869–1954), linocut illustration and initial in Henry de Montherlant (1895–

1972), Pasiphaé, Chant de Minos (Les Crétois).Paris: Martin Fabiani, 1944. Frances and Michael Baylson Collection, The Morgan Library & Museum. © 2015 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photography by Graham S. Haber, 2015.

Henri Matisse (1869–1954), preliminary study for the etching in the Circe chapter, Ulysses

(1934). Collection of The Pierre and Tana Matisse Foundation © 2015 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photography by Graham S. Haber, 2015.

Henri Matisse (1869–1954), rejected cover design for Les fleurs du mal (1946). Collection

of The Pierre and Tana Matisse Foundation © 2015 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights

Society (ARS), New York. Photography by Graham S. Haber, 2015.

Henri Matisse (1869–1954), Icarus, pochoir, plate VIII, Jazz (1947). Courtesy of Frances and Michael Baylson © 2015 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photography by Graham S. Haber, 2015.

Henri Matisse (1869–1954), Le Toboggan, pochoir, plate XX in Jazz (1947). Courtesy of Frances and Michael Baylson © 2015 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photography by Graham S. Haber, 2015.