She Who Wrote:

Enheduanna & Women of Mesopotamia, ca. 3400-2000 BC

Reviewed by Ed Voves

Over the years, the Morgan Library and Museum has mounted a number of outstanding exhibitions highlighting the brilliant achievements of women writers and artists.

Here are just a few of these Morgan presentations that spring to mind: A Woman's Wit: Jane Austin's Life and Legacy (2009-2010); I'm Nobody! Who are You? the Life and Poetry of Emily Dickinson (2017); and one of my "top ten" exhibits, Charlotte Bronte: an Independent Will (2016-2017).

During 2020-2021, many centennial events were planned by museums in tribute to the 19th Amendment giving American women the right to vote. It was only to be expected that the curators at the Morgan would mount an exhibition to celebrate a notable woman or a theme related to women's history - and indeed they did have one scheduled for the autumn of 2021. Their choice of topic was brilliant, if unusual: the story of Enheduanna, history's first writer.

Let us underscore this fact, Enheduanna, a noble woman from ancient Mesopotamia, was the first author, male or female, to be recorded in the annals of civilization.

Events - in the shape of the Covid-19 pandemic - interfered with the Morgan's exhibition. Entitled She Who Wrote: Enheduanna and Women of Mesopotamia, ca. 3400-2000 BC, it was delayed until October 2022. The exhibit, now in its final days, is a splendid one, but Enhedeuanna's long wait for recognition is actually a very long story and a rather complicated one.

Enheduanna was the daughter of Sargon of Akkad, the conquering warlord who united the city states of Mesopotamia into what many regard as history's first empire.

Enheduanna, whose name means "high priestess, ornament of heaven," lived around 2300 BC. She was a politically powerful figure during her lifetime and remained influential through her writings for many centuries afterward.

Eventually, Enheduanna faded into the dust of the past. Then, in 1927, a circular stone object was uncovered in an archaeological "dig" in present day Iraq. Measuring 10 1/8 inches (25 cm) in diameter and 2 3/4 inches (7 cm) thick, the alabaster Disk of Enheduanna had been smashed into fragments thousands of years ago. But once it was pieced together, it portrayed Enheduanna, in a profile view, showing her as a priestess engaged in a religious ritual.

A cuneiform tablet, created at a later date in antiquity, displayed a poem written by Enheduanna, The Exaltation of Inanna.

These archaeological finds are immensely important, proving that Enheduanna was a major writer, many centuries before Homer or Herodotus. Yet, it has taken decades since these discoveries for her status and literary stature to be fully recognized.

The announcement of firm, archaeological evidence of the first author in history should have been a "stop the presses" event. Had the identity been that of an already well-known figure like Sargon or a person in some way related to the Holy Bible, the event would have almost certainly received greater publicity.

As a woman, virtually unknown to history, Enheduanna had one strike - a big one - against her. Two more strikes made it even more difficult for her to get the credit she deserves.

In 1922, the discovery of the tomb of King Tutankamun raised the bar of ancient celebrity status to a very high degree. And then, in the same year that the Disk of Enheduanna was unearthed, another dramatic discovery was made, this time at Ur, Enheduanna's own "backyard." This revelation all but consigned her to the footnotes of the annual archaeological reports of field work in Mesopotamia.

In 1927, Leonard Woolley, the same archaeologist who found the battered pieces of the Disk of Enheduanna, excavated the tomb of Queen Puabi, filled with exquisite treasures including her glittering headdress, ear rings and necklaces, believed by some art lovers to be the most beautiful royal regalia in all of history.

One of the major incentives in visiting the Morgan exhibition is the impressive display of Puabi's "crown" or headdress, on loan from the University of Pennsylvania Museum. In a sense, Puabi is upstaging Enheduanna again, as the breathtakingly beautiful ensemble of gold jewelry and precious stone beads dominates much of the exhibition gallery. But thanks to the Morgan's curator, Sidney Babcock, Enheduanna eventually asserts her own royal presence.

Throughout much of in the twentieth century, Enheduanna languished in the shadows of the fine print of scholarly journals. Then in 1968, a very detailed study of Enheduanna's poem, The Exaltatation of Inanna, was made by a noted scholar, William Hallo, assisted by J.J.A. van Dijk. Hallo's book is the kind of academic work almost never read by the public, but it established beyond doubt that Enheduanna was one ot the pioneers of world literature:

...at or near the beginning of classical Sumerian literature, we can now discern a corpus of poetry of the very first rank which not only reveals its author's name, but delineates the author for us in truly autobiographical fashion. In the person of Enheduanna, we are confronted by a woman who was at once princess, priestess and poetess, a personality who set the standards in all of her roles for many succeeding centuries, and whose merits were recognized, in singular Mesopotamian fashion, long after.

This is precisely what the Morgan exhibition asserts, so memorably and cogently, with a trove of treasures related to Enheduanna and the women of Mesopotamia.

Queen Puabi lived around 2500 BC, approximately two centuries before Enheduanna. Both women resided in the city of Ur and were Akkadians, that is members of the Semitic-speaking nobility, rather than the indigenous Sumerians, who had been subjected to Akkadian rule. Although the focus of the Morgan's exhibit is the role of women in Mesopotamia, a subtext - which cannot be ignored - is the dynastic politics which directly engaged both Puabi and Enheduanna.

When Sargon completed the Akkadian take-over of Mesopotamia, Enheduanna was installed as high priestess of the cult of the moon god, Nanna, of Ur. But her most important duty was to promote the assimilation of Sumerian religious beliefs to those of the Akkadian ruling elite.

Enheduanna the poet is given credit for a major poem or hymn, The Exaltation of Inanna. To Akkadians like Enheduanna, Inanna was known as Ishtar or Istar. Over the centuries, Inanna/Ishtar would reappear in the Greek world as Aphrodite, goddess of love. Inanna/Ishtar certainly promoted beauty and fertility in Mesopotamia but, especially as Ishtar, this goddess was also a terrifying exponent of war.

The dual faces of Inanna/Ishtar are brilliantly contrasted in the Morgan exhibition by two important artifacts.

The first is a fragment of a vessel showing a Sumerian goddess, probably Inanna. Dating to ca. 2400 BC, this divine being reveals an earth goddess character. It evokes the nourishing, life-sustaining agricultural revolution which made Sumer the template for all of the later Mesopotamian - and Western - societies.

Ishtar, as she is appears in an impression made by a cylinder seal, is very different. Her face, masterfully carved by the intaglio process, so that the diminutive seal could be pressed into clay, projects an impassive savagery. This withering look is reinforced by the lion she grips by a leash and the battle-axe or mace which she holds in her other hand.

Enheduanna's own words, as set-down in cuneiform on a one-tablet edition of The Exaltation of Inanna, dating to 1750 BC, reveal the shifts from nurture to aggression which could happen without warning. At first, we are regaled with visions of Inanna's benevolence.

Queen of all cosmic powers, bright light shining from above,

Steadfast woman, arrayed in splendor, beloved of earth and sky,

In the second stanza, the mood shifts to images of destruction and war.

You spew venom on a country, like a dragon.

Wherever you raise your voice, like a tempest, no crop is left standing.

These are hardly the comforting, humane sentiments provided by the Morgan's exhibitions on Jane Austin and Emily Dickinson! Needless-to-say, Enheduanna's era was very different from England and America during the 1800's. It was a very violent world. The foot of Ishtar, firmly planted on the lion's rump on the cylinder seal impression (above), likely symbolizes the military campaigns waged by Sargon and his successors to repel raiders from the deserts surrounding Mesopotamia

Enheduanna composed hymn poems to appease Inanna/Ishtar, who could turn from a caring, protective deity to a wrathful one with the suddenness of a river in flood or a blinding sandstorm. Enheduanna knew from personal experience what rapid shifts in political fortune could bring. At one point, she was driven into exile when a usurper seized control of Ur.

The Morgan curators utilize the surviving archaeological evidence to confirm what Hallo asserted back in 1968. Enheduanna, as "princess, priestess and poetess" did "set the standards in all of her roles for many succeeding centuries..."

Two principal means of illustrating Enheduanna's life and times are used: a brilliant selection of cylinder seals with modern-day impressions and an imposing array of statues and figurines depicting the women of Mesopotamia, perhaps Enheduanna herself.

It is almost a miracle that Enheduanna's image in profile survived the smash-up of the Disk of Enheduanna. This was certainly an act of politically-motivated vandalism. Enheduanna is shown to be an older, full-faced woman on the Disk. It is tempting to think that perhaps the serene Seated Female Figure with Vessel in Hands, from Ur, III period (ca. 2112–2004 BC) might be a representation of Enheduanna.

Could the fragmentary statuette of a woman with arching "Frida Kahlo" eyebrows be Enheduanna? Or might she be the formidable High Priestess with glaring inlaid eyes?

All this is idle, almost silly, speculation. What these small statues identify is not a particular person but the strength, intelligence and resilience of the women of Mesopotamia, talents which Enheduanna certainly exemplified.

Resilience, most of all. The ability to endure hard work, the constant risk of famine or floods and the ever-present threat of war characterized the lives of the women of the ancient Sumerian cities.

This durability seems to have rubbed-off on the striking alabaster figure of a be-robed woman, found by German archaeologists in a temple complex in Assur, the birthplace of the later Assyrian Empire. This lady worshiper, battered but unbowed, survived the destruction of the Assyrian strongholds during the seventh century BC. Then, after being unearthed shortly before World War I, she nearly succumbed to the aerial bombardment and Soviet assault on Berlin during World War II. That's a lot of history to endure!

While these statues anchor the Morgan exhibition (along with Puabi's regalia), perhaps the most important works to complement The Disk of Enheduanna are the amazing cylinder seals.

When pressed into clay or other substances, the cylinder (carved into a rare, precious stone like lapis lazuli) created a sealing bond over documents, vessels, containers, even doors, a bond that could not be broken except when properly mandated.

The scenes which emerge, as if by magic, when the cylinder is rolled over clay illustrate Enheduanna's beliefs and poems, in short, her world. There is no better way to comprehend Enheduanna and Mesopotamian culture than to spend time studying cylinder seals, of which the Morgan possesses one of the finest collections among American museums.

It is some regret to me that I was only able to make one short visit to She Who Wrote: Enheduanna and Women of Mesopotamia, and post a last-minute review. But the Morgan exhibition is so brilliant that I could not let it go without the notice and praise which it deserves.

Thanks to She Who Wrote: Enheduanna and Women of Mesopotamia at the Morgan Library and Museum, Enheduanna's honored place in literature and history now seems secure. That could change, however. Our world, built on apparently secure foundations is actually a fragile edifice, as Enheduanna well knew.

Vulnerable to desert storms, political folly and human forgetfulness, civilization can soon return to the sands.

Text: Copyright of Ed Voves, all rights reserved

Introductory image courtesy of the Morgan Library & Museum and the Louvre

Introductory Image:

Seated Female Figure with Vessel in Hands. Mesopotamia, Neo-Sumerian, Girsu (modern Tello) Ur III period (ca. 2112–2004 BC). Musée d' Louvre © MN-Grand Palais

Ed Voves, Photo (2022) Entrance to the exhibition, She Who Wrote: Enheduanna and Women of Mesopotamia, ca. 3400-2000 BC, at the Morgan Library and Museum.

Ed Voves, Photo (2022) Gallery view of She Who Wrote: Enheduanna and Women of Mesopotamia, ca. 3400-2000 BC at the Morgan Library and Museum.

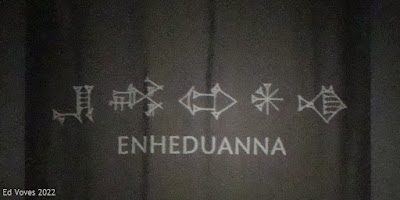

Ed Voves, Photo (2022) Enheduanna's Name in Cuneiform from the gallery of the Morgan exhibition, She Who Wrote: Enheduanna and Women of Mesopotamia, ca. 3400-2000 BC.

Ed Voves, Photo (2022) The Disk of Enheduanna. Mesopotamia, Akkadian, Ur (modern Tell el- Muqayyar), gipar, ca. 2300 BC. Collection the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology & Anthropology.

Ed Voves, Photo (2022) Tablet inscribed with The Exaltation of Inanna, poem by Enheduanna. Mesopotamia, Nippur (modern Nuffar), ca. 1750 BC. Collection the University of Pennsylvania Museum.

Ed Voves, Photo (2022) Queen Puabi’s Funerary Ensemble. Mesopotamia, Sumerian, Ur (modern Tell el-Muqayyar), Early Dynastic IIIa period,ca. 2500 BC. Collection of the University of Pennsylvania Museum.

Ed Voves, Photo (2022) Gallery view of the Enheduanna exhibition at the Morgan Library and Museum showing Queen Puabi’s Funerary Ensemble.

Ed Voves, Photo (2022) Sidney Babcock of of the Morgan Library and Museum, with The Disk of Enheduanna.

Ed Voves, Photo (2022) Gallery view of She Who Wrote: Enheduanna and Women of Mesopotamia, ca. 3400-2000 BC at the Morgan Library and Museum.

Ed Voves, Photo (2022) Fragment of a Vessel with Frontal Image of a Goddess. Mesopotamia, Sumerian, Early Dynastic, IIIb period, ca. 2400 BC. Collection of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin-Vorderasiatisches Museum.

Ed Voves, Photo (2022) Cylinder seal (and modern impression) The Goddesses Ninishkun and Ishtar. Mesopotamia, Akkadian, ca. 2334–2154 BC. Collection of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

Ed Voves, Photo (2022) Gallery view of She Who Wrote: Enheduanna and Women of Mesopotamia, with a votive figurine in the foreground and Queen Puabi’s Funerary Ensemble.

Ed Voves, Photo (2022) Detail of The Disk of Enheduanna.

Ed Voves, Photo (2022) Seated Female Fgure with Vessel in Hands, ca. 2112–2004 BC. (Details above). Collection of the Musée d' Louvre.

Ed Voves, Photo (2022) Fragment of a Statuette of a Female Figure, possibly from Umma (modern Tell Jokha). Akkadian period, 2334-2154 BC) Collection of the Musée d' Louvre.

Ed Voves, Photo (2022) Head of a High Priestess (?) with inlaid eyes. Mesopotamia, Akkadian, Ur (modern Tell el-Muqayyar), ca. 2334–2154 BC. Collection of the University of Pennsylvania Museum.

Ed Voves Photo (2022) Standing Female Figure. Mesopotamia. Assur, Ishtar Temple, ca. 2400 BC. Alabaster. Collection of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin-Vorderasiatisches Museum

Ed Voves, Photo (2022) Cylinder seal (and modern impression) Shumshani, High Priestess of the Sun God. Mesopotamia, Akkadian, Sippar (modern Tell Abu Habbah) , ca. 2250 BC. Lapis Lazuli. Collection of the Morgan Library and Museum.

Ed Voves, Photo (2022) Cylinder seal (and modern impression) Ishtar Receiving Worshipper: Hero Combating Lion. Mesopotamia, Akkadian, ca. 2250 BC. Lapis lazili. Collection of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin-Vorderasiatisches Museum

Ed Voves, Photo (2022) Cylinder seal (and modern impression) Shumshani, High Priestess of the Sun God (as above).

_2013.31.8.jpg)