May 18 - September 8, 2024

It proved to be a dazzling debut. The dozen exhibited works included three superb pastels. But the standouts were two magnificent oil paintings - a beautiful portrait of a young woman at the Paris Opera and an unforgettable depiction of a bored, mischievous child sprawled on a blue-upholstered arm chair.

Mary Cassatt at Work will surely delight art lovers who make the pilgrimage to Philadelphia to see it. With 130 works of art on view - oil paintings, works in pastel and prints - the exhibition curators at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA) needed every square inch of gleaming, glistening gallery space to do justice to Cassatt's achievements.

It's high time to celebrate

Cassatt's amazing artistic career. Mary

Cassatt at Work is the first major exhibition of the great American

Impressionist to be held by a U.S. museum in a quarter of a century. Back in

1998-99, the Art Institute of Chicago, the National Gallery of Art in

Washington D.C. and the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston presented Mary Cassatt: Modern Woman. Despite the

rousing success of this exhibition, Cassatt retrospectives remain surprisingly

rare.

To focus on Cassatt’s “modernity” is to risk forgetting

that she was a Victorian, a Victorian radical, certainly, but still a person of

her era.

During the Victorian age, the “gospel of work” was a favorite theme of social commentators. The virtues of labor and industry were usually ascribed to the formidable, bewhiskered gentleman of the era.

Given

Cassatt’s frequent choice of scenes of family life and leisure as her chosen subject, one could be

excused for thinking that she somehow found a way to ignore or evade the

moralizing sermons of men like John Ruskin, who called for an embrace of “the

pleasure and arduousness of useful, physical labor.”

I don’t think that Cassatt and Ruskin would have agreed

on much else, but on the importance of work, these two “eminent” Victorians

were in complete accord.

Two years of intensive study of the 84 works of art by Cassatt in the PMA collection enabled curators, Jennifer A. Thompson and Laurel Garber, to grasp the importance of work for Cassatt. Toil and fortitude, exacting attention to technique and a proud sense of professionalism were revealed as key determinants of Cassatt's character.

Mary Stevenson Cassatt (1844-1926) came from a wealthy American family, though not extravagantly so by the Robber Baron standards of the post-Civil War era. Cassatt’s parents – who were otherwise devoted to her - refused to subsidize her career in the hope that she would resume a more ladylike attitude toward life and art: get married and paint for pleasure.

Cassatt was not content with

painting as a gentile, feminine accomplishment. She was driven to succeed

commercially, desiring pay for her efforts rather than faint praise. The

foundation of Cassatt’s success as a professional artist, first noticed at the

1879 Impressionist exhibition, can be summed up in that one word: work.

Work. Diligent, dedicated effort, characterized by the courage to try, fail and try again.

Cassatt’s determination to create

great works of art led her to express her attitude toward labor in remarks that

now seem deliberately composed for inclusion in Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations:

“I work & that is the whole secret of anything like

conten(ment) with life.”

“I am independent! I can live alone & I love my

work.”

“What one would like to leave behind is superior art and

a hidden personality.”

For Cassatt, these

assertions expressed the simple, unvarnished truth of her life. For historians

and students of art, Cassatt ‘s “hidden personality” is a call to action.

Cassatt’s genius can be

observed in the details of her paintings, pastels and prints. In the introduction to

the exhibition catalog, Thompson and Garber direct our attention to the hands

of the women Cassatt painted or, in the case of The Banjo Lesson, depicted with pastel.

Thompson and Garber perceptively comment on the never "idle" hands of Cassatt's protagonists.

Despite the spontaneity of her style, Cassatt’s attentive

depictions of hands, whether at rest or in motion – wetting a towel, plucking a

banjo or holding a book, balancing horse reins or cradling a nursing child –

demonstrate that she was very much in control. These details challenge the idea

that her oeuvre focuses solely on moments of leisure.

In fact, close study of

Cassatt’s work reveals that she excluded everything except serious, purposeful

activity by her female protagonists. No lawn tennis playing or bicycle riding, very

popular activities for spirited American girls of her era. No amateur dabbling

with sketch books or water colors!

This view of Cassatt as a

thorough professional - rather than a gentile painter of mothers and infants - may come as a jolt. Mary Cassatt at Work has quite

a number of surprises in store. Be prepared to entertain new interpretations of

Cassatt and her oeuvre!

The first “concern” to be

addressed is the absence of several of the greatest and most beloved paintings

by Cassatt. Every special exhibition presents challenges about which signature works of

art “must” be included and those that, for one reason or another, elude the curators' grasp.

It was a real privilege to

be able to see Lydia at a Tapestry Frame (1880) from the Flint Institute of Art.

This was surely an essential Cassatt painting for a “Work” themed exhibition. The

Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Young Mother

Sewing (1900) also addresses this topic, but is not on view. The Met loaned

other important works, notably Lydia

Crocheting in the Garden at Marly (1880) which I will discuss in a

follow-up essay.

More serious are the omission of key Cassatt paintings from the National Gallery in Washington, like The Boating Party. But this is due to the stipulation of the Chester Dale Collection at the National Galley that its paintings may not travel to other museums. The National Gallery did send Little Girl in a Blue Arm Chair, a truly sensational work of art, which benefited from Degas' assistance soon after he met Cassatt in 1877.

Cassatt's introduction to printmaking came from the same source as her invitation to join the Impressionists, Edgar Degas. Cassatt had studied traditional engraving techniques under an Italian master, Carlo Raimundi, in 1872. But it was the daring, unconventional nature of Degas' art, beginning with some of his pastels which Cassatt saw in a dealer's window in Paris, which "changed my life. I saw art then as I wanted to see it."

After viewing prints by Cassatt, Degas recruited her to join with him, Camille Pissarro and Felix Bracquemond to produce a journal of engravings to be entitled Le Jour et la nuit. This was to be a new version of "impressionism" - images pressed onto paper, a visionary, modernist approach to a time-honored medium.

Unfortunately, Le Jour et la nuit never progressed beyond the planning stages. Cassatt was deeply disappointed. But preoccupied with exhibiting at the Impressionist exhibitions of the 1880's and caring for her elderly parents who had come to live with her in France, Cassatt had little time for printmaking initiatives on her own.

In 1890, this frustrating situation changed radically. A vast exhibition of Japanese woodblock prints, held at the Ecole des Beaux Arts, seized hold of Cassatt's imagination after she visited the show with Degas.

"You who want to make color prints," Cassatt wrote to Berthe Morisot, "you couldn't dream of anything more beautiful. I dream of it and don't think of anything else but color on copper."

Cassatt determined to do a series of 10 color prints, each illustrating an incident from a related topic, the daily lives of Parisian women. Unlike the Japanese woodblock printers, she would use the etching/aquatint on copper plate process, as she mentioned to Morisot.

Although Cassatt hired a professional printer to assist her, she did much of the exacting, messy and potentially hazardous work herself!

Rather than discuss Cassatt's printing technique in a review like this, the wisest course is to leave this subject to the experts. In the case of Mary Cassatt at Work, this is Christina Taylor, Conservator for Works of Art on Paper at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. With the help of Laurel Garber and Tom Primeau, Taylor recreated, step-by-step, the printmaking process used by Cassatt to make The Letter (the original shown above).

A video recording of Taylor at work on her version of The Letter is featured in the exhibition gallery dedicated to Cassatt's "The Ten" and is also available in a longer version on YouTube. This video brilliantly complements the works of art on display in Mary Cassatt at Work and is highly recommended.

After watching the video, visitors are well-primed to understand Cassatt's exacting and exhausting printmaking regimen. One entire wall of the gallery is devoted to showing the progressive versions or "states" of one of the series of depictions of Parisian women. Starting with Cassatt's preliminary drawing, it concludes with the seventeenth state of seventeen of The Bath.

The ten final plates were utilized to create limited-edition sets of 25 prints of each. These were marketed by Cassatt's dealer, the renowned Paul Durand Ruel. The complete series of prints of "The Ten" is displayed on the opposite wall, making this gallery a tour de force presentation of classic printmaking and Cassatt's unrivaled application of the process.

What should have been a singular artistic and financial success proved to be a frustrating disappointment. Despite all the innovations going on in the Parisian art world of the 1890's, connoisseurs were not prepared for Cassatt's "The Ten" prints.

The test of time has yielded a different verdict on "The Ten" series. Adelyn Breeskin, long-time head of the Baltimore Museum of Art and a major Cassatt scholar, declared that Cassatt’s prints were “her most original contribution… technically, as color prints they have never been surpassed.”

The amount of gallery space devoted to Cassatt's prints raises a major

point of concern. Is too much attention being devoted to Cassatt’s softground

etchings and drypoint prints?

After some reflection on the matter, I feel that the curators have made the correct decisions, vis-a-vis the amount of relative attention paid to paintings and prints in the exhibition.

It is Cassatt's pastels - it seems to me -which need more emphasis in the galleries of Mary Cassatt at Work.

Although there is an excellent chapter in the exhibit catalog on Cassatt's pastels, I think that a gallery devoted primarily to pastels would have greatly enriched our appreciation of Cassatt "the worker." It was pastels upon which Cassatt relied to continue her career as cataracts imperiled her vision, leading eventually to almost complete blindness.

A similar case study can be found in the life of Henri Matisse. Faced with ill health and a life-threatening abdominal cancer operation, Matisse turned to making illustrations for special edition art books, livre d'artiste, cutting out designs with scissors and specially colored art paper. The recent exhibition at the PMA, Matisse in the 1930's devoted a special gallery to these late-career works on paper.

A comparable display focusing on Cassett's pastels would have done much to increase our understanding of Cassett's efforts to keep working, as the tide of life began to shift away from her.

However we approach Cassatt's pastels, these beautiful, sensitive works deserve to be studied and appreciated. They need to be valued aesthetically for the marvelous technique which Cassatt devoted to them, the related facility of hand and eye.

Ultimately, Cassatt's pastels are statements on human values, tenderness, empathy, caring and sharing.

In a forthcoming essay on Cassatt, I intend to reflect upon her humane feeling and the way it nurtured her art Cassatt's loving relationship with her sister, Lydia, will receive special attention. And some comment will be made on Cassatt's predeliction for painting mothers and babies, as an extension of her life.

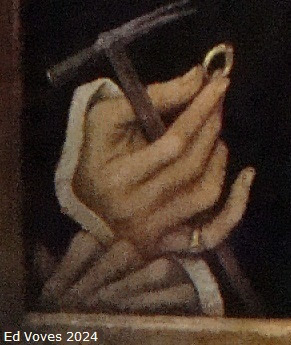

For now, let us close with a detail from my favorite of Cassatt's pastels, The Banjo Lesson (1894)

Mary Stevenson Cassatt was reputed to be a strong-willed, "difficult" woman. No doubt she was ambitious, driven to succeed. She could be antagonistic toward rivals like "that woman" Celia Beaux or haughtily dismissive, "What Sargent wants is fame and a great reputation."

But nobody paints or creates with pastel such a scene of warmth and humanity as this, unless there is a glowing ember or two of love and compassion deep within their hearts.

***

Text: Copyright of Ed Voves, all rights reserved

Original photography, copyright of Anne

Lloyd

Introductory Image:

Anne Lloyd,

Photo (2024) Detail of Mary Cassatt’s Driving,

1881. Oil on canvas: 34 7/8 x 51 in. (88.8 x 129.8 cm.) Philadelphia Museum of

Art.

Anne Lloyd,

Photo (2024) Gallery view of the Mary

Cassatt at Work exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024) Mary

Cassatt’s Woman in a Loge, 1879. Oil on canvas: 32 1/16 × 23 7/16 in. (81.5

× 59.5 cm Philadelphia Museum of Art # 1978-1-5

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024) Mary

Cassatt’s Little Girl in a Blue Armchair, 1877-78. Oil on canvas: 35

1/4 × 51 1/8 inches (89.5 × 129.9 cm National Gallery of Art, Washington #

1983.1.18

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024) Signature of Mary Cassatt on Bathing the Young Heir, 1890-91

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024) View of the East Entrance of the Philadelphia

Museum of Art, showing banners advertising the Mary Cassatt at Work exhibit.

Anne Lloyd,

Photo (2024 ) Gallery view of the Mary Cassatt at Work exhibition at the

Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024) Mary

Cassatt’s Maternal Caress, 1896. Oil

on canvas: 15 × 21 1/4 inches (38.1 × 54 cm Philadelphia Museum of Art

Anne Lloyd,

Photo (2024) Copy of a photo of Mary

Cassatt, Paris, c. 1867

Anne Lloyd,

Photo (2024) Detail of Mary Cassatt’s The

Banjo Lesson, 1894. (Full citation below.)

Anne Lloyd,

Photo (2024 ) Gallery view of the Mary Cassatt at Work exhibition,

showing Mary Cassatt’s Lydia at a Tapestry Frame, 1880.

Anne Lloyd,

Photo (2024) Detail of Mary Cassatt’s Little Girl in a Blue Armchair,

1877-78. (Full citation

above.)

Anne Lloyd,

Photo (2024 ) Gallery view of the Mary Cassatt at Work exhibit, showing

three states of Mary Cassatt’s The Fitting, 1890-1891. Drypoint and aquatint on wove paper. From the

Cohn Family collection and the Cleveland Museum of Art.

Anne Lloyd,

Photo (2024) Detail of Mary Cassatt’s print, The Letter.

Anne Lloyd,

Photo (2024) Video image showing

Anne Lloyd,

Photo (2024) Detail of Mary Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024 ) Gallery view of the Mary

Cassatt at Work exhibit, showing the

original drawing and early print states of Mary Cassatt’s The Bath, 1890-91.

Mary

Stevenson Cassatt (American, 1844-1926) The

Bath, 1890-1891. Color drypoint,

soft-ground etching, and aquatint on laid paper, seventeenth state of

seventeen: Plate: 12 5/8 × 9 3/4 inches (32.1 × 24.7 cm) Sheet: 17 3/16 × 11

13/16 inches (43.6 × 30 cm) Mat: 22 × 18 inches (55.9 × 45.7 cm. Art Institute

of Chicago

Anne Lloyd,

Photo (2024 ) Gallery view of the Mary Cassatt at Work exhibition,

showing Mary Cassatt’s “The Ten” prints.

Anne Lloyd,

Photo (2024) Mary Cassatt’s Woman Bathing,

1890-91. Color drypoint and aquatint on laid paper: 14 ½ x 10 3/8 inches (36.8

inches x 26.3 cm) From a private collection.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024) Mary Cassatt’s Sailor

Boy: Portrait of Gardner Cassatt as a Child, 1892. Pastel on paper Sheet: 25 × 19

inches (63.5 × 48.3 cm. Philadelphia Museum of Art

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024) Mary Cassatt’s Ellen Mary Cassatt, c.1889. Pastel on laid paper: 12 ×

14 1/2 inches (30.5 × 36.8 cm) The Metropolitan Museum of Art. # 60.132.1

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2024) Mary Cassatt’s The

Banjo Lesson, 1894.

Pastel over oiled pastel on paper: 28 × 22 1/2 inches (71.1 × 57.2 cm). Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)