Catholica: the Visual Culture of Catholicism

By Suzanna Ivanic

Thames & Hudson, $35, 256 pages

Reviewed by Ed Voves

For over a thousand years, the Christian Church was the greatest patron of the arts and architecture in the world. Beginning in the year 312, when the Roman emperor Constantine embraced Christianity, almost every aspect of thought, culture and craft in Europe was dominated by the effort to build and maintain a civilization based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth.

Catholica, a brilliant new book published by Thames and Hudson, explores the visual record of Roman Catholicism. This was the dominant form of Christianity in Europe, until it was divided into warring camps by the publication of Martin Luther's radical views on religious doctrine in 1517.

Despite the Reformation, Roman Catholicism survived - and thrived. This was due in no small part because of the impact of Catholic art and the religious convictions upon which it was founded. After losing control over parts of Germany, England and the Netherlands, Roman Catholicism spread to Latin America, much of sub-Saharan Africa and to Asian countries like the Philippines.

Roman Catholicism still exerts a strong and inspiring influence over millions of faithful Christians the world over. Yet many of its works of art, or sacred objects like the vestments worn by Catholic clergy and vessels used in devotional ceremonies, have an unfamiliar, even unsettling, feel to them.

For instance, many people today have no idea as to the significance of the golden vessel known as the monstrance.

The monstrance is used to display the Host, unleavened bread transformed into Christ's body during the Mass. The role and importance of this sacred object is, needless to say, difficult to grasp by those unacquainted with Roman Catholicism. Thanks to Catholica, the process of understanding and appreciating Christian art and ideas will be a great deal easier.

Catholica was written by Suzanna Ivanic, who teaches history at the University of Kent, England. Ivanic has excellent credentials for investigating the works of art, architecture and artifacts of Catholicism, for her research field (according to the publisher's blurb) is the "lived religion and material and visual culture in Central Europe."

Equally important, Ivanic writes with conviction and insight. Indeed, the sensitivity of her commentary and the scope of her knowledge are awesome and admirable.

Catholica is organized into three parts. Tenet surveys the basics of Roman Catholic religious doctrine; Locus examines the sites where Catholics worship, ranging from magnificent Gothic cathedrals to prayer sites in the homes of the faithful; Spiritus focuses on Christian devotion, as practiced by communities and by individuals.

As noted above, many Catholic works of art or devotional objects may be unfamiliar. In some cases, they are "wondrously strange" and Ivanic has her work cut-out to explain them. This she does in "decoding" units where baffling, arcane details of famous paintings and church architecture are analyzed.

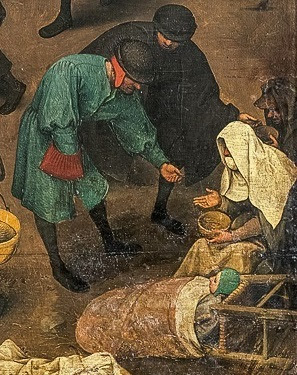

The Fight Between Carnival and Lent, painted by Pieter Bruegel the Elder in 1559 is one of the masterpieces decoded by Ivanic. Indeed, it was created with exactly that purpose in mind. A wealth of examples of folly, greed, gluttony and social mayhem during Mardi Gras was included in Bruegel's painting. These are compared with the sober performance of Christian charity during the season of Lent.

Other "decoded" paintings include The Penitent Magdalen by Georges de la Tour (c. 1640) and Caravaggio's The Seven Works of Mercy (1607).

A fascinating Japanese screen painting, dating to the early 1600's, shows Catholic missionaries from the Jesuit and Franciscan orders in one of its vignettes. Here we can see the global outreach of Christianity as seen - and very attentively examined - by non-Europeans.

Profiles of important themes in Christian culture also feature prominently in the book. These range widely from the important events and rites associated with the seasons of Christmas and Easter, the "roles" assigned to the Virgin Mary - Mother of Sorrows, Mary of the Rosary, etc. - and the Catholic ways of coping with Death. This last profile is especially compelling, as I will comment in more detail later in this review.

With this investigative format in mind, it might seem that Catholica is primarily a reference work. Indeed it is, but the best way to appreciate Catholica is to begin on page one and follow Ivanic as she guides us along the path of Roman Catholicism's engagement with art of the spirt.

The profoundly moving nature of Ivanic's text is due to more than her command of source material. She writes about matters of religious faith with a real sense of what Christian belief in God and the divine ordering of the universe is like.

A brief quotation from Ivanic's discussion of the role of Abbot Suger (1081-1151) regarding the rise of Gothic cathedrals is indicative of the marvelous and moving narrative of Catholica:

Key to understanding the birth of the Gothic is Suger's emphasis on the transformative power of the liturgical performance. Just as during the Mass the bread and wine are turned into the body and blood of Christ, so does the ritual performance of the cathedral transform it from stones, glass and metal into a divinely powerful space...

Christianity traces its origin to Judaism. Like Jews, Christians base their beliefs on the written (and sanctified) words of the Bible. But early in the history of the Christian Church, images of Jesus, the Virgin Mary and saints like the Apostle Peter were treated with an unprecedented sense of importance.

Pope Gregory I (540-604) realized that visual representations of the episodes of Biblical history and the life of Jesus were essential teaching tools. Vast numbers of Christians were illiterate and thus excluded from reflecting upon and understanding what they heard preached by the Christian clergy.

Yet, images of Jesus and other saintly people from the Bible were potentially dangerous. Pope Gregory was aware that Christians might come to adore sacred pictures or religious objects, rather than worship God. It was a risk he felt compelled to take. Ivanic quotes Gregory's famous, and hugely influential, pronouncement.

It is one thing to worship a picture and another to learn from the story of a picture what is to be worshiped. For what writing conveys to those who can read, a picture shows to the ignorant ... and for that very reason a picture is like a lesson for the people.

To understand a picture, people need to identify with its subject and message. As a result, depictions of the great events of the Bible and the life of Jesus stressed relevancy rather than historical accuracy of setting and costume. Artists frequently showed biblical characters in contemporary attire, surrounded by details of architecture and artifacts similar to those of the people gathered together to view such works of art as part of Christian worship.

Catholic images were modified to suit geography and social convention as part of the Christian missionary movement. One of the book's most fascinating images comes from Ethiopia in the 1600's where Jesuit missionaries sought to influence the Christian population to embrace Catholicism, rather than the version they practiced which was based on the Coptic Church of Egypt.

The diptych above presents episodes from the life of Mary, mother of Jesus. The bottom scene of the left-hand panel presents Mary showing the infant Jesus to the Three Kings, who look like Ethiopian nobles rather than magi from the Middle East. Above, shepherds, having already seen Jesus, play a hockey-like game called genna.

Unfortunately, such culturally-sensitive artwork did not always convince. The mass of Ethiopia's people resisted conversion to Catholicism, even when the country's ruler, Emperor Susenyos, did so in 1622. After years of dissension and civil war, the Jesuit mission ended in failure.

Spanish missionaries experienced greater success in grafting Catholic cultural forms onto native roots in Mexico, Peru and other Latin American nations. The process led to the creation of enduring expressions of Christian piety. The image of Our Lady of Guadalupe (below) was based on the religious visions of a Mexican native, Juan Diego, in 1531, only a few years after the Spanish conquest of the Aztecs.

Juan Diego's vision of Mary was depicted in various amalgams of ethnic attributes and styles of clothing. The facial features of Our Lady of Guadalupe in this version, almost obscured by layers of sumptuous Spanish robes, bears a strong resemblance to the Aztec earth goddess, Tonatzin.

Roman Catholicism never missed an opportunity to present the guiding principles of Christianity in ways that believers and would-be believers could appreciate and enjoy. From soaring stained glass windows to the charming maiolica ensemble of movable figures at the Last Supper, Catholic art was on view everywhere one looked.

Maiolica model of the Last Supper, from Faenza, Italy, 1500's

Judged in this manner, Roman Catholic art represents an early - and very successful - form of corporate "branding." But there is one staggering difference.

Modern-day public relations techniques emphasize sprightly images and upbeat banter to keep customers buying, consuming and buying some more in an endless cycle of happy days and Happy Meals. Roman Catholicism, by contrast, fixated upon the inevitable negation of earthly pleasure and human life by Death.

The supreme symbol of Roman Catholicism is the Cross, the emblem based upon the crucifixion of Jesus. This form of torture and execution was reserved for slaves and criminals under Roman rule.

Early Christians did not display the Cross, so terrible was the memory of Jesus' execution. Also, they lived in the daily expectation of the End Time. When the Apocalypse did not come, the brutal fact of Jesus' crucifixion remained. But so too, did the Christian believe that Jesus had secured redemption for them from sin, with the promise of immortal life for the souls of those who believed in him.

Death, Christ's death, has conquered death.

This paradox, which St. Paul called the "scandal of the Cross," placed the reviled symbol of a slave's execution at the summit of human devotion, a place it still holds for millions. Christians, especially Roman Catholics, have created, collected and cherished works of art related to the Crucifixion since the Middle Ages and continue to do so.

From sublime depictions of the Crucifixion by Giotto and Velazquez to harrowing, nightmarish portraits of Jesus, like Aelbert Bouts' The Man of Sorrows, c. 1525, to tattooed images of the crucified Christ on human skin, the Cross is ubiquitous, recognizable to believers and detractors alike.

There will never - hopefully - be a final word on Christian art. For now, in a deeply troubled world, menaced by disease and war, Susanna Ivanic's Catholica is a much needed volume. To her, we will leave the final word.

The art of Catholicism is the art of the human condition. Devotional artworks that dwell on the gaze of the grieving mother or the lifeless body of Jesus resonate with the soul. They are designed to raise one's spirit and deepen one's reservoirs of faith, inspiring intense, reverential joy and pain.

***

Text: Copyright of Ed Voves, all rights reserved.

Introductory Image: Cover art for Catholica by Suzanna Ivanic. Courtesy of Thames & Hudson

Diego de Atienza (Spanish, born in Ecuador, 1610) Monstrance, c. 1646. Silver gilt with enamel, cast, chased, and engraved: Height: 22 1/2 in. (57.2 cm) Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Friedsam Collection, Bequest of Michael Friedsam, 1931. #32.100.231a, b.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder The Fight Between Carnival and Lent, 1559, Oil-on-panel: 118 cm × 164 cm (46 in × 65 in). Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

Anonymous (Japan) The Arrival of the Europeans, early 1600's. Pair of six-panel folding screens; ink, color, gold, and gold leaf on paper: each screen: 41 3/8 in. × 8 ft. 6 5/8 in. (105.1 × 260.7 cm) Metropolitan Museum of Art. Mary Griggs Burke Collection, Gift of the Mary and Jackson Burke Foundation, 2015. #2015.300.109.1, .2

Master of the Church Fathers' Border (German, late 15th century) The Mass of Saint Gregory, late 1400's. Metalcut with traces of hand-coloring; second state: 13-7/8 x 19-15/16 in.; 10-5/8 x 7-7/16 in. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1924 # 2448

Anonymous (Ethiopia) Diptych of Life of Virgin Mary, c. 1630's-1700. Wooden diptych: distemper, gesso and cloth, each painted panel having three registers, H x W x D: 51.7 x 43 x 2.5 cm (20 3/8 x 16 15/16 x 1 in.). Smithsonian National Museum of African Art. Gift of Ciro R. Taddeo in memory of Raffael and Alessandra Taddeo. #98-3-3

Anonymous (Mexico) Our Virgin & Child of Guadalupe, 1745. Oil on canvas:106 x 84.5 cm. Wellcome Library, London. #44828i

The Last Supper (Faenza, Italy), 1500's. Tin-glazed earthenware (maiolica): H. 8 1/2"; W. 12 5/6" (14 3/4" with base); L. 22 7/8" (24 1/2" with base) Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Bequest of R. Thornton Wilson in memory of Florence Ellsworth Wilson #1983.61

Aelbert Bouts & workshop (Netherlandish, ca. 1451/54–1549) The Man of Sorrows, c. 1525. Oil on oak: arched top, 17 1/2 x 11 1/4 in. (44.5 x 28.6 cm) Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Friedsam Collection, Bequest of Michael Friedsam, 1931. # 32.100.55

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment