Art Day by Day: 366 Brushes with History

Reviewed by Ed Voves

Like many art lovers, I have a daily calendar in my office which provides a full-color artwork for each day of the year. It's great way to get "going" in the morning. Flip the page and discover a new work of art or greet an old favorite.

Thames & Hudson's new book, Art Day by Day: 366 Brushes with History, seemed to be in the the same vein. Each new day brings fascinating excerpts from diaries, journals, letters, autobiographies, business contracts and other source materials. These daily helpings of art history provide insights into the lives both of great masters and forgotten artists.

I looked forward to Art Day by Day as a likely candidate for review in Art Eyewitness. There was one problem, apparent as soon as I opened the book.

Art Day by Day: 366 Brushes with History is all text. No pictures.

Considering that Art Day by Day deals with the visual arts, the omission of illustrations was a bit of surprise, almost a shock. It is a rare art book today - as opposed to those published only a few decades ago - which does not feature high caliber color pictures. Thames and Hudson, the publisher of Art Day by Day, is one of the pioneers of juxtaposing pictures with text, notably in their World of Art series.

Within a few minutes I had completely forgotten about the lack of pictures. This is a brilliant book, brimming with life experience, joys and sorrows, achievement and failure, visionary ideals and incredible folly. I found Art Day by Day hard to put down.

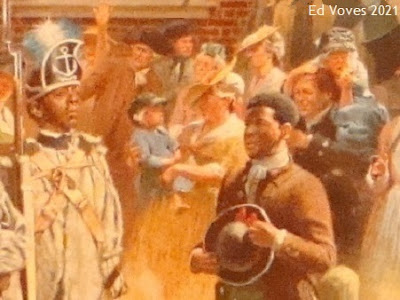

The issue of illustrations did reappear, however, as I was moved to check on works of art or artists I had not heard about. I include some of these researched images here, for the sake of creating a visually stimulating review. But it needs to be emphasized that Art Day by Day succeeds by virtue of the quality of thought and writing which went into its making. If ever there was an art book which does not need pictures, this is the one.

Art Day by Day is a brilliant compilation of stories about all aspects of the visual arts. While particular attention is given to Western art - largely because the documentation is better - numerous entries are devoted to other cultures as well.

Each daily entry in Art Day by Day begins with a direct quotation from primary source material, followed by succinct, always insightful and often-times humorous, commentary. This is provided by Alex Johnson, the British journalist who conceived the idea for this remarkable book.

There is literally something for everybody in Art Day by Day. This includes romance.

The February 20th entry records the 1864 marriage of the "British Michelangelo" George Frederic Watts, to the sixteen year-old actress, Ellen Terry. Watts painted Terry, who was thirty years younger than he, in the act of selecting camellias or violets. Entitled Choosing, the painting evokes "a symbolic choice between worldly goods and loftier values."

Ellen Terry certainly made her choice, but it was not the one that Watts hoped for. Johnson notes that after ten months of marriage, Terry returned to her family. She and Watts later divorced - amicably.

One of the really notable features of Art Day by Day is Johnson's facility in selecting incidents which correspond with others appearing at earlier or later times of the year/book. Many of the art stories which Johnson features are unfamiliar but often are linked with more famous ones. In this way, a sense of communion across time and space is achieved, providing opportunities for deep-thinking without being aware you are doing it.

A especially noteworthy example occurs with the contrast in fame and fortune of the Briitish artist, William Hodges (1744-1797) with Paul Gauguin (1848-1903). Perhaps it would be more accurate to say "contrast in fame and misfortune."

William Hodges appears in the entry for July 13th, the date he sailed on Captain James Cook's second voyage to the Pacific Ocean in 1772. Hodges was a gifted landscape painter, creating memorable images of Tahiti and several historic "firsts." These included the first paintings of Easter Island and of Antarctica. Upon his return to Britain, however, the exhibition of his works from the voyage was largely ignored and he suffered a devastating investment disaster. Hodges died, broken and forgotten, until a 2004 exhibition revived the memory of his amazing achievements.

Gauguin, likewise, lost his money and job as a stock broker in an 1880's bank bust. Gauguin's first journey to Tahiti in 1891 is noted in the June 9th entry. The quote from his diary records his disgust at finding Polynesian culture "under the maddening grip of colonial snobbery, and the imitation, grotesque to the point of caricature, of our customs, fashions, vices and farces of civilization."

Another impressive feature of Alex Johnson's selection process is his ability to find obscure, yet revelatory, moments in the well-studied lives of major artists. These pithy, unexpected, insights help us see the Old Masters in a new light.

Johnson highlights the famous visit of Albrecht Dürer to Brussels on August 27, 1520, when he saw gold and silver treasures seized from the Aztecs by Hernan Cortes and sent to Emperor Charles V. Five years later (August 5), Dürer, had a disturbing dream of a vast rain storm.

Whether this dream had a deep, symbolical import, related to the Reformation, is impossible to say. But Dürer's description of "wind and roaring so frightening, that when I woke up my whole body was shaking" certainly explains why he went to such extraordinary lengths to both depict and describe his "traumgesicht".

Apart from the connections between certain artists or topics, the daily subject matter of the Art Day by Day is determined by the calendar alone. Some of the events discussed in the book are there because they simply happened. The discovery of the Hoxne Hoard in 1992 came about because a farmer in rural England, Peter Whatling, lost an old hammer in his fields.

With the help of a friend who had metal detector, Whatling went looking for his hammer. What he found was a sensational stash of treasure, dating to the end of Roman rule in Britain. During that chaotic time, the Hoxne Hoard was buried to keep it safe but its owner never lived to retrieve it.

The Hoxne Hoard has helped historians better understand one of the least documented eras in British history. Yet, its discovery was a chance occurence. Life "happened" one day in a Suffolk field in 1992. No lost hammer, no unearthed Roman treasure trove.

Random, unexpected, events like finding the Hoxne Hoard happen from time to time. But the overall tenor of the events recorded in Art Day by Day testify to the creative ordeal of Humankind over time and transcending circumstance.

Howard Carter's 1923 discovery of Tutankhamun's burial chamber (February 16) was the result of an epic search, an archaeological campaign, years in the making. The following day's entry recounts the horrifying POW experiences of British artist Ronald Searle, captured by the Japanese when Singapore fell on February 15, 1942. Searle secretly recorded life and death during the building of the Kwai Railroad, a powerful record of the tragedy and triumph of the human spirit.

While many of the daily entries in Art Day by Day are rooted in the personal experience of artists, Johnson also addresses major, society-wide issues. Human destructiveness, as well as creativity, is examined with several entries devoted to the periodic efforts to smash and burn the artistic legacy of the past. Some of these misdeeds are "one-off" acts of arson such as the destruction of the Temple of Artemis in 356 BC (July 21) by Herostratus, who sought fame by committing an act of infamy.

Most of the efforts to efface art result from carefully orchestrated campaigns to achieve "noble" goals. Joseph Goebbels, who carried out the Degenerate Art purge in Nazi Germany (March 20 and June 4) did far more damage than the Vandals who stripped gold and bronze roof tiles from the temples of Rome in 455 (June 2). Compared to "civilized" men, barbarians are mere amateurs in the art of desecration.

The entry for February 19th records the chilling language of the edict of the Byzantine emperor and compliant bishops, ordering the destruction of Christian paintings and relics in 754. These misguided bureaucrats were certainly sincere, believing that the citizens of the Byzantine Empire were venerating sacred objects rather than worshiping their divine creator. Acting in the name of God, these "iconoclasts" wiped-out centuries of spiritual and artistic achievement. Iconoclasm, the name generally given to all such efforts to destroy art, was their dubious contribution to the story of civilization.

Art Day by Day is thus a record of the darker recesses of the human psyche, as well as our sublime side. But it is not just an "oh, so serious" book. The ridiculous has its place too.

Johnson included topics which more conventional art historians might regard as frivolous or inconsequential. The entry for June 5th records the visit of Ferris Bueller to the Art Institute of Chicago in the 1985 movie, Ferris Bueller's Day Off. A few days earlier, May 27th's entry finds Charles Darwin feeling that his 1855 photographic portrait made him look "atrociously wicked."

Darwin's photo actually gives the impression that he was a banker or a lawyer, rather than a scientist. Perhaps, he was correct in his negative assessment, after all.

If life and culture often appear "grotesque to the point of caricature" as Gauguin said, the experience of art does testify to one absolute. Creative talent will find a way to express itself and be appreciated, even if it takes a long time before being recognized. That was true of William Hodges, as we saw earlier, and so too for Augusta Savage (1892-1962), the great African-American sculptor.

It seems entirely appropriate the the entry for Augusta Savage should be the "leap year" date of February 29th. Beginning with the opposition of her father, a devout Christian whose opinion on art was much like that of the Byzantine iconoclasts, Savage had to struggle against all manner of adversities in order to create art. When she applied to study at the Fontainbleau School of Fine Arts in France, she was denied a scholarship because she was Black. Later, during the 1930's, her leadership of the Harlem Community Art Center, was undermined by behind-the-scenes intrigue. Most likely, the root cause was resentment that Savage was a woman.

The greatest tragedy of Savage's artistic career, brilliantly summarized by Alex Johnson, was the destruction of her magnum opus, The Harp. Inspired by James Weldon Johnson's poem, Lift Every Voice and Sing, The Harp was a sixteen foot sculpture, cast in plaster with a finish resembling black basalt. It was exhibited in 1939 to wide acclaim at the New York World's Fair. Sadly, The Harp had to be demolished along with other artists' works made for the Fair. Savage could not find patronage to make a full-scale bronze cast of her masterpiece.

Ed Voves, Photo (2019) Gallery view of the Augusta Savage: Renaissance Woman exhibition at the New York Historical Society

All that remains of The Harp are several small scale versions which Savage was able to cast, One of these was on view in the New York Historical Society's 2019 exhibition devote to Augusta Savage. It was a profoundly moving display and one of the high points, so far, in my Art Eyewitness reviews.

By the time the December entries appeared in Art Day by Day, I was already downcast by the thought that I was reaching the end of the book. Alex Johnson, however, was not going to let the "year" pass without a suitable finale. Like all good story tellers, he knows to "leave 'em laughing."

The December 31st entry recounts the incredible story of the banquet held in a dinosaur-shaped dining space at the Chrystal Palace in 1853. A group of Eminent Victorians, including Sir Richard Owen, the palaeontologist who coined the name for the prehistoric reptiles, "terrible lizards" or dinosaurs, met for a legendary dinner party.

The dining space was actually the mold created by sculptor Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins (1807-1894) to make a huge, cement statue of an Iguandon, one of the first dinosaurs to be discovered.

Hawkins' version of Iguanodon looks nothing like the actual creature which lived during the early Cretaceous Period, about 125 million years ago. Iguandon was a leaf-eating contemporary and "dining companion" of T Rex. Hawkins made the head of his Iguanodon look like a turtle, albeit with a small rhinoceros-like horn, presumably to defend itself from T-Rex.

The assumed resemblance of Iguanodon to a turtle is all the more ironic since the first item on the New Year's Eve menu at the Chrystal Palace banquet was Mock Turtle Soup.

***

Text: Copyright of Ed Voves

Introductory Image: Cover art of Art Day by Day: 366 Brushes with History by Alex Johnson. Courtesy of Thames & Hudson

George Frederic Watts (British, 1817-1904) Ellen Terry ('Choosing'),1864. Oil on strawboard mounted on Gatorfoam: 18 5/8 in. x 13 7/8 in. (472 mm x 352 mm). National Portrait Gallery, London. Accepted in lieu of tax by H.M. Government and allocated to the Gallery, 1975. Primary Collection, NPG 5048

William Hodges (British, 1744-1797) A View of Matavai Bay in the Island of Otaheite, Tahiti, 1776. Oil on Canvas: 36 inches x 54.01 inches. (91.4 × 137.2 cm) Yale Center for British Art. #B1981.25.343

Albrecht Dürer (German, 1471-1528) Traumgesicht (Dream Vision), 1525. Watercolor and ink on paper: 30 x 42.5 cm. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Traumgesicht_(D%C3%BCrer).jpg

Hammer, associated to the Hoxne Hoard, 20th century. Iron, with wood handle: Length: 393 millimetres. British Museum. #1994,0408.410

The Hoxne 'Empress' Pepper Pot, created between 300-400 AD, buried in late Fifth century. Findspot: Hoxne, Suffolk. Silver & Gold cast, chased and gilded: Diameter: 33 millimetres; Height: 103 millimetres; Weight: 107.90 grammes; Width: 57.90 millimetres. British Museum #1994,0408.33

Ronald Searle (British, 1920-2011) In the Jungle - Working on a Cutting. Rock Clearing after Blasting, 1943. Drawing on paper with pencil and ink: 216 mm x 171 mm. Imperial War Museum, IWM # 15747 87. © Imperial War Museum

Illustration showing Iconoclasm, from the Chludov Psalter, c. 850–875. Illuminated manuscript: 19.5 x 15 cm. State Historical Museum, Moscow. MS. D.129), folio 67r. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Crucifixion_with_iconoclasts,Chludov_Psalter,_folio_67r.jpg

Maull & Polyblank Studio. Charles Darwin, c. 1855. Albumen photographic print, arched top: 7 7/8 in. x 5 3/4 in. (200 mm x 146 mm) National Portrait Gallery, London. Purchased, 1978. Primary Collection NPG P106(7)

Ed Voves, Photo (2019) Gallery view of the Augusta Savage: Renaissance Woman exhibition at the New York Historical Society. A miniature bronze version of Savage's The Harp appears in the foreground.

Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins (British, 1807-1894) Joseph Prestwich’s invitation to the Dinner in the Dinosaur, 1853. Lithograph with manuscript additions. Joseph Prestwich Tract series .The Archives of the Geological Society. https://blog.geolsoc.org.uk/2021/04/15/the-first-dinosaurs-dinner/