New York: 1962-1964

Jewish Museum, New York City

July 22, 2022 - January 8, 2023

Reviewed by Ed Voves

Original Photography by Anne Lloyd

One Thousand Days. This was the title of one of the most praised and popular non-fiction books of the 1960's. Written by Arthur Schlesinger Jr., One Thousand Days chronicled President John F. Kennedy's administration, from his inauguration in January 1961 to the fatal Friday in Dallas, November 22, 1963.

The Jewish Museum in New York City has just opened a brilliant and ambitious exhibition surveying the American art scene during a similar span of the early 1960's. The chronology is not an exact fit, but it's close. The years covered by the exhibition extend from 1962 to 1964.

Why these three years? The course of events during this period marked the abrupt transition from the ironclad ascendancy of Abstract Expressionism to the wide-open, consumer-conscious theater of Pop Art. Social ideals, in keeping with the political goals of President Kennedy's New Frontier and the Civil Rights movement, likewise made their presence felt.

New York: 1962-1964 is a big, colorful art show, currently spread over two floors at the Jewish Museum. The exhibition guides us through these eventful years with major works of art and provocative gallery texts about the role of culture in American society.

Yet, there is nostalgic touch to New York: 1962-1964 which will appeal to those old enough to remember the Camelot years - and to later generations still affected by its mystique.

Anne Lloyd, Photo (2022) Gallery view of New York:1962-1964, with a vintage jukebox, courtesy of New York Jukebox

The exhibit opens by displaying a jukebox, that potent symbol of Sixties pop culture.Pick a song. "Love is a Swingin' Thing" by the Shirelles? "Leader of the Pack" by the Shangrilas? The curators of the Jewish Museum selected a soundtrack of "hit tunes" which will have you dancing through the first floor galleries.

Then, on the second floor, the mood changes. A poignant and powerful array of JFK-related memorabilia and works of art awaits. As with the actual events, 59 years ago, the shocking assassination of President Kennedy casts a sense of mourning over the rest of the exhibition.

A six minute video-loop of Walter Cronkite, grappling with his emotions as he announced the death of President Kennedy, and Andy Warhol's Jackie Frieze are on view. Both are still heart-wrenching after all these years.

At this point, we should ask a further question related to the years, 1962-1964. Why did the Jewish Museum decide to focus on these "thousand days" of art for a major exhibition? The answer can be found in the dynamic role of the Jewish Museum itself during this period.

In March 1962, a much-anticipated display of drawings and paintings by Willem de Kooning opened at the Sidney Janis Gallery. Surprisingly, the show occasioned hostile criticism and poor sales. A few months later, the Janis Gallery tried a different tack with an exhibit highlighting younger artists, entitled New Realists.

The exhibition opened on October 31, 1962, only days after the Cuban Missile crisis. The New York art scene was sharply divided as Pop Art came to town with Andy Warhol's 200 Campbell Soup Cans leading the charge. The New York Times styled New Realists as "mad, mad, wonderfully mad" but "welcome." The "Ab-Ex" establishment, however was infuriated, with Mark Rothko, Robert Motherwell and others severing ties with the Janis Gallery.

Navigating his way through this crossfire of contention, Dr. Alan Solomon (1920-1970) took over the directorship of the Jewish Museum in July 1962. His two-year tenure at the museum anchors the time-line of this exhibition.

An outstanding scholar and curator, Solomon turned the Jewish Museum into a major forum for appreciating modern art. Solomon had a keen insight into the art of his own era and promoted young, innovative artists. He mounted exhibitions of the work of Robert Rauschenberg (1963) and Jasper Johns (1964) at the Jewish Museum. These were watershed events at the time and, decades later, provide the foundation for New York:1962-1964.

Art works by Rauschenberg and Johns figure prominently in the Jewish Museum exhibit. What especially impresses me, however, is the diversity of artists included in the show, not just the big names, and the strikingly off-beat curatorial values. Both were hallmarks of Solomon's methodology at the Jewish Museum.

Solomon had particular regard for Rauschenberg's "combines." These were created from a wide-variety of materials, pieced-together to evoke moods and modes of life, often defying easy comprehension.

Such works, Solomon stated in an influential 1963 essay, were rooted in an "intense passion for direct experience, for unqualified participation in the richness of our immediate world."

There can be no better description or summing-up of the works of art on view in New York: 1962-1964.

A huge, multi-paneled oil painting entitled The Eye of Lightning Billy dominates the first gallery of the exhibition. Painted by an Oklahoma-born artist named Harold Stevenson, it appeared in the New Realists exhibition in October 1962. An impressive, if alarming, work, this depiction of the eye of a Native American cowboy leaves the viewer wondering just who is watching whom.

We are left to question too about the identity of this work. Is The Eye of Lightning Billy a Realist painting? Is it Pop Art or perhaps Surrealism? All or none of the above?

For Solomon, works like The Eye of Lightning Billy did not fit securely into a narrowly defined artistic canon or "school." And that is exactly what he wanted, art which was drawn from everyday life, “familiar, public, and often disquieting.”

Solomon referred to the works he promoted at the Jewish Museum as the "New Art." This was a revival of the title initially used to describe the paintings of Monet, Renoir and Pissarro by the critic Edmund Duranty in 1874, before the originally scornful term, Impressionism, was adapted as a badge of honor. Like his nineteenth century forebearers, Solomon championed art that was experimental and expressive, yet rooted in the "here and the now."

That, at least initially, was the backdrop for Louise Nevelson's ominous Sky Cathedral’s Presence I, created over the course of 1959–62. Nevelson watched the destruction of New York City's working class neighborhoods to make way for the "urban renewal" plans of Robert Moses.

After being evicted from her residence in the Kips Bay neighborhood of New York City, Nevelson responded to Moses' "slum clearance," by collecting castaway objects, just as Rauschenberg was doing. With these and thick layers of black paint, Nevelson created Sky Cathedral’s Presence I.

Nevelson's art, however, was not merely reactive. Sky Cathedral's Presence I was deeply grounded in spiritual ideals. With this powerful sculpture, and similar works produced over the following years, Nevelson aimed to reach "the in-between places, the dawns and dusk, the objective world, the heavenly spheres, the places between the land and the sea."

For many people during the early 1960's, the image of "heavenly spheres" did not have much to do with "in-between places." Rather, they thought in terms of the Project Mercury rockets which launched NASA astronauts like John Glenn into orbit. Except for a fortunate few able to travel to the beaches near Cape Canaveral, watching the Project Mercury lift-offs was done from a reclining armchair positioned in front of a television set.

The idea of "home entertainment centers" with wide-screen monitors and Dolby Sound was beyond the wildest dreams of all but a few tech-savvy engineers during the 1960's. But to watch a NASA rocket blasting into Outer Space on a TV in your living room was still a big deal.

The impact of television was felt everywhere in the Sixties' art world. Rauschenberg embraced the televised, black and white drama of a NASA space launch in Glider.

Not surprisingly for a work by Rauschenberg, one really has to search Glider to find the rocket blasting-off, positioned just above a human hand on the left hand side of the canvas.

If Rauschenberg engaged with television, Andy Warhol's Empire reacted in direct contrast. In many an American home, the "boob tube" droned relentlessly from morning till midnight. Warhol directed a 16 mm camera to record what everyone was missing while they watched TV - the effect of light, natural and electric, as reflected on and around the spire of skyscraper.

The skyscraper was, of course, the Empire State Building, making for a dramatic setting. Nothing much happened,however, in the eight-hour filming session, the sun set and the building lights came on. Yet, Warhol and his film-making partners, Jonas Mekas and John Palmer, had captured a moment of astonishing transcendence - "as though the world had been recreated" to quote an appreciative critic.

Thanks to the curators of New York: 1962-1964, we are able to relive that moment.

Few people have the time or patience to watch an eight-hour film. For most Americans of Warhol's era, it was the appliances and accoutrements of their "Affluent Society" that interested them. The Jewish Museum curators have done a terrific job in evoking the material culture of the early 1960's, clock radios, electric coffee pots, slick magazines and stylish apparel like Evelyn Jablow's Fold-Up Dress for a Portable Society (1964).

Another dress appeared the same year, 1964, as the Fold-Up: the topless Monokini bathing suit. Designed by Rudi Gernreich, it was intended as a protest against America's puritanical values (according to Gernreich). Whether that was true - or just a clever sales technique - the advertisement and sale of the Monokini led to a storm of controversy.

GIven the sheer number of topics covered in New York, 1962-1964, the Jewish Museum curators wisely avoid detailed commentary on these debates. But the Monokini's inclusion in the exhibition does set the stage for art works by woman artists who very much wanted to protest against the treatment of the female body as an "object" available at your local newstand in "pin-up" magazines.

Marjorie Strider and Marisol Escobar, in different ways, asserted the right of women to define own identities, free from societal expectations or male desires..

Strider's Girl with Radish, 1963, appeared in a 1964 exhibit, The First International Girlie Show, along with works by Roy Lichtenstein, Andy Warhol and. Rosilyn Drexler, who is also featured in New York: 1962-1964. "Girlie Show" was one of the first Pop exhibits and many critics regarded Strider's painting - and Pop generally - as a stunt rather than serious art. Strider, however, was not joking with her confrontational reworking of comic book sexuality.

Kristina Parsons, one of the Jewish Museum curators of New York, 1962-1964, comments on Strider's "engagement with the power dynamics of voyeurism." Strider, Parsons notes, "combines a kind of sly humor and a little bit of bite. Strider often features women who are staring deliberately out at the viewer, rejecting the one-directional gaze of an often male viewer consuming a female's image."

Marisol Escobar, or simply Marisol, joined with Rauschenberg and Nevelson in reusing debris from the "throw-away" society around her as source material for her art. She even somehow found human teeth to use in the mouths of the figures comprising the identities of her Self-Portrait.

Just who are these enigmatic folks? Only one of the seven faces looks like Marisol herself. Two, maybe three, are male and who the duck-billed creature might be is anyone's guess. Do they represent various facets of Marisol's personality?

Perhaps the best explanation for this remarkable work of art is that Marisol created it to deliberately leave us guessing. While we are scratching our heads in bemusement, Marisol affirms that she - and she alone - defines her own, true, identity.

Artistic statements are, for the most part, personal manifestos. Most of the works on the first floor galleries of New York: 1962-64 are individual responses to events transpiring during those incredible years. But art has a community, collegial "ethic" and the Jewish Museum exhibition does not neglect this aspect of the early 1960's.

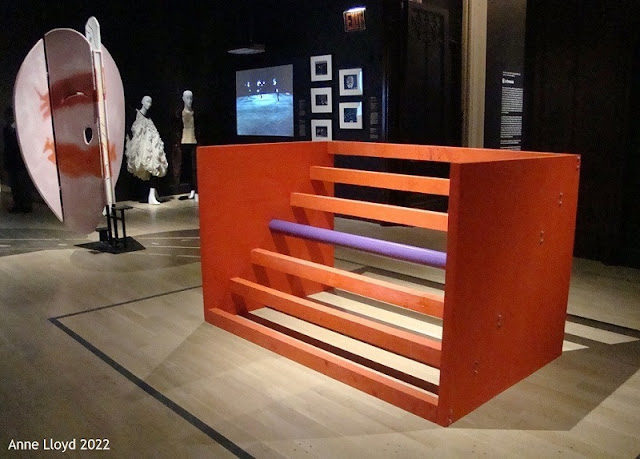

Modern dance played a major role in the New York cultural scene during the 1960's. Although Solomon was not directly involved with dance, Rauschenberg was. He designed costumes for Merce Cunningam's company, provided sets and choreography for the Judson Dance Theater and even danced himself in one production, on roller skates with a parachute suspended on his shoulders!

The Jewish Museum exhibits several of Rauschenberg's costumes for Merce Cunningham's Antic Meet. Also on view is the spectacular stage prop, the Shrine of Aphrodite designed by Isamu Noguchi for the controversial 1962 ballet, Phaedra, by Martha Graham.

Artists, acting with a sense of community, found unity in social action, which in turn led many to create powerful works of art supporting the Civil Rights Movement. Most of the artists whose works are on view in New York: 1962-1964, lived and worked in run-down areas of Lower-Manhattan. Labeled the "Loft Generation" they had a natural sympathy with African-Americans battling against segregation and discrimination.

The extensive array of art related to the Civil Rights era, on view in New York: 1962-1964, is truly impressive. Paintings by Faith Ringold and Norman Lewis, photos by Bruce Davidson and Roy De Carava, videos of the the "I have a Dream Speech" and an interview with Malcolm X make these galleries a virtual exhibition is its own right.

Although not as well known today as Lewis or Ringold, Reginald Gammon was a great artist and a dedicated Civil Rights activist. Born in Philadelphia, Gammon settled in New York city after World War II service in the Navy. His Freedom Now!, a splendid evocation of the spirit of the Civil Rights movement, appeared in a major exhibition at the Christopher Street Gallery in 1965.

Gammon's Freedom Now! embodied the "spirit of the age" of the early 1960's America. This positive, almost unquestioned, belief in ourselves and our ability to overcome our failings and realize our nation's destiny, was real and widespread. And this sense of confidence and "mission" suffered a terrible, if not fatal, wound on November 22, 1963.

As I mentioned earlier in this review, the array of art and artifacts related to President Kennedy's murder and America's prolonged anguish is deeply moving.

It was only after we returned from the Jewish Museum and examined Anne's photos that we noticed a strange effect of light and reflection on one of pictures. In a amazing way, impossible to plan or orchestrate, one image was mirrored in another to create a new image with its own special impact.

Looking at a photo of the LIFE magazine dedicated to the memory of President Kennedy, we saw reflected the somber face of Walter Cronkite announcing Kennedy's death, joined in a photo montage effect. This left Anne and I shaking our heads in wonderment. It was a compelling and chilling image all in one.

New York: 1962-1964 is a magnificent exhibition. The curators at the Jewish Museum have brought back to life a short-lived era of exceptional achievement. Their task in preparing the exhibition was made vastly more difficult by the death of the great Italian scholar who had planned and organized New York: 1962-1964. Germano Celant, died from Covid-19 before seeing the project to completion. Judging from the emotion in the voice of Claudia Gould, director of the Jewish Museum, as she spoke of Mr. Celant at the press preview, his death was a great loss.

One can only admire Ms. Gould and the staff of the Jewish Museum, all the more, for completing the preparation of New York: 1962-64 and sharing it with lovers of art.

And what of Dr. Alan Solomon, the guiding mind and directing hand for much of what we see celebrated in New York: 1962-1964?

Sadly, Alan Solomon too was cut-down in his prime, dying from a heart attack in 1970, aged 49. His death, like JFK's, left a void of unrealized promise, never to be fulfilled.